However unpleasant the circumstances, there will always be people who would be proponents of the past, whatever the regime or the political system at that time. This seems to be the case especially in post-communist countries, for which the transition into a democracy does not always go smoothly. In light of this, during our trip to the Czech Republic, we asked citizens of Prague the question:‘If you could bring back one item from the times of Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (CSSR) what would it be and why?’ in the hope of creating a memory suitcase, which offers a look back at the past through the eyes of ordinary people.

Anonymous, Czech Republic, 1956

‘The most important thing was the certainty of professional employment, which was there for everyone. For example, nowadays the capitalist system does not offer chances for people, around and older than 60. Young people can find jobs easily everywhere, but the case for older people is not like that.

Now, I have the possibility to travel – something that I could not do before. I can go to Paris if I want to. Problem is, now that I have the opportunity, I am unemployed and do not have the money to seize it. Personally, I think it is really hard to decide what is more important – a person’s freedom, or the certainty a job provides.‘

Jaroslav, Czech Republic, 1941

Jaroslav, Czech Republic, 1941

‘It was a negative experience for me as a whole. I do remember some good things from that time, though. Mainly, my wife was so young. But now I have the chance to enjoy the positive aspects of a democratic system and nothing comes close to that.‘

Jaroslav, Czech Republic, 1973

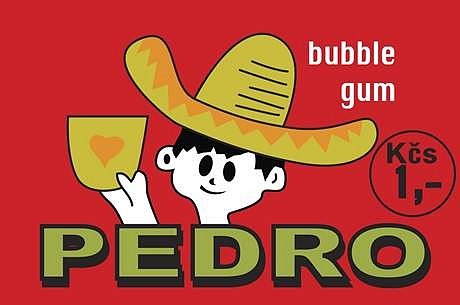

‘It is hard to say. There was a general lack of products as opposed to the surplus of goods in modern society and that was tough. What I am certain of is that I miss Pedro bubblegum.

‘It is hard to say. There was a general lack of products as opposed to the surplus of goods in modern society and that was tough. What I am certain of is that I miss Pedro bubblegum.

What is more, there was this general feeling of safety, though I am not sure I can attribute that exactly to the regime.‘

Jaroslav & Jaroslav (Audio recording in Czech)

Anna and Anton, Slovak Republic, 1948 and 1945

Anna: ‘Life was more quiet and calm. There were not so many murders, the crime rate was lower generally. I was not afraid of going out and walking along Wenceslav’s square alone at night.‘

Anton: ‘There was no fear of getting fired, because everyone had to be engaged in the economy, including the minorities.‘

Anna & Anton (Audio recording in Czech)

Milan, Czech Republic, 1970

Milan, Czech Republic, 1970

‘Socialism was wrong. Without a doubt, I do not miss anything from that time. My family was put in jail, because they were enemies of the regime. I remember I was a pioneer for three months but then they drove me out because of that. These times were the most terrible moment of my life.

For example, at the time of the communist regime, if you were to ask me such a question, like ‘Do you miss anything from the capitalist Czechoslovakian First Republic?’, you would have problems with the authorities.

There is not anything nice about communism. The certainty of employment is completely untrue. Everyone had a job, because five people did what a single person should have been doing. Compared to western countries, all of our goods and products were of inferior quality. During a communist regime, both a country’s economy and its system of human rights completely stop functioning.’

Milan (Audio recording in Czech)

Aleš, Czech Republic, 1982

Aleš, Czech Republic, 1982

‘I especially liked uzeniny (smoked meat). Everything was fresh and without additives. The quality of food was better. Society was united because they were fighting against a common enemy – the communist party. The unfairness of the regime brought people together. There were some positive aspects, but I would never go willingly back to that time.’

Aleš (Audio recording in Czech)

An important step in studying the past is focusing on the individual. This is especially true for regimes, which rely on conformity to seize control of the masses and condemn critical thinking because it threatens their rule. Taking this into account, we have tried to put a face to people, whom the political system considered merely a part of the faceless crowd. Looking at the past through their personal stories, we hope to uncover details that history books often leave unsaid.