Can you imagine going to the toilet in the middle of the night and seeing something that will change your life and your country forever? The 8th of May marks the 71st anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe, and Mr Chojcknaki shares his memories about the Second World War and how it changed him and where he called home.

An Encounter at Galeria Revita Warmia

Mr. Chojnacki (Photo: Tina Gotthardt)

In front of the gallery “Galeria Revita Warmia” in the village Jeziorany, found in the Polish region Warmia-Mazury, an old man was sitting on a bench and enjoying the first glimpses of sunlight on this otherwise cloudy Saturday. Although it definitely was a lovely bench, he wasn’t just sitting there to enjoy the sunshine, he was patiently waiting. Inside the gallery we, half of the participants of the interview-group from the History Camp-project “Regional eye”, were preparing for the interview with him, a historical witness named Mr. Chojnacki.

This was of course an exceptional opportunity for us, and even though everyone felt a bit nervous, there was no reason to. Mr. Chojnacki stepped in to the gallery, and even though he didn’t speak a word of English, he nodded to all of us and gave us a friendly smile while he was guided to his chair by the translator. Together with him we formed a circle of chairs, but he was still the centre of it. All eyes were fixed upon Mr. Chojnacki, fascinated by this man who had lived through so much and had so many memories. Hopefully we could now get him to share some of them with us.

Insights From a Witness of History

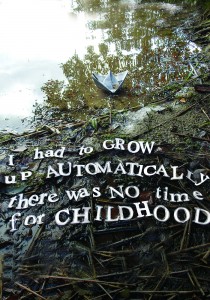

Poster Art by Bodil Bartroff, Denmark

Mr. Chojnacki began by letting us introduce ourselves by name and country, and then he properly presented himself. He was born in 1930 and grew up just 20 meters from the Polish-German Border. He saw the first the first German troops cross the border one night when he was on his way to the toilet. We were all so completely captivated by this 85 year old man none of us had our pens ready when he started talking about his experiences of the Second World War. Even so, the message was clear: The war had come to Poland.

This was the subject we had been waiting for and in pairs we were finally able to ask him our questions. We began with uncomplicated questions and he told us about a normal day in his childhood, which he specified was incomparable to a childhood today due to the hard work, as he said: “I had no childhood. I had to grow up automatically.” He didn’t seem sad about it, it was merely just a fact and now time had among other things changed that for many children as well. He was very relaxed and we began to feel like we had little by little opened the door to his more personal life and memories. Even those who couldn’t understand a Polish word could feel the emotions and memories inside our little improvised interview room.

Mr. Chojnacki’s Wartime Recollections

Interview in the Gallery (Photo: Tina Gotthardt)

He began telling us about what it was like growing up during the wartime, with minimum food and German soldiers in the area, who burned down the village and displaced the residents in another town. There was nothing else to do during the war, other than trying to survive: “I used to work all the time, minding the animals, helping people. That was the only way we could make a living and feed the family. We had nothing.”

When the Russians came in 1945, the family decided to move to Jeziorany, which used to be in Germany, but since the borders were redefined, the region is now Polish. His family was the second family in the entire village, so could choose the house they wanted – they picked their house by measuring which one had the most room for storage. The house they chose, has earlier belonged to a German engineer. There were still Russians in the area years after the war, which sometimes made it unsafe, but Mr. Chojnacki described how everyone in the village looked after each other and helped the newcomers, which created a strong bond between the families.

Identity and Belonging

Since our “Regional Eye” project among other things was to explore whether people feel like their national or regional identity is the strongest, we asked Mr. Chojnacki. when he began to feel like home in the region of Warmia-Mazury. He answered that he early on felt like he was born here, but the biggest reason was “that the war was over (…)I like towns like Jeziorany because almost everyone knows each other. It’s like being in a family.” It didn’t have anything specifically to do with the village or region, but more with the peace and security from the war.

In their new village there was water, a place to live and a community which grew strong – something he felt was missing in the big cities and today’s society. But even though his early childhood wasn’t spent in this area, it was still the area he preferred to call home. Of course there were still big changes going on, especially since Poland was now ruled by Communism, but he had a very plain attitude about it: “I had to work to live. Communism or no Communism, it doesn’t matter; people are people.” Throughout this part of the interview, it was clear that he didn’t distinguish between the general lives in different political systems. We did ask him about his life during the period of Communism in Poland, and although he was a member of the party, he didn’t care much for it.

Navigating Censorship and Adversity

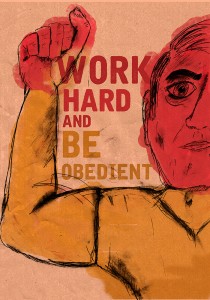

Poster Art by Paweł Zaborowski, Poland

The only thing that seemed to bother him was the censorship, as he started to work as photographer. He was once assigned to take pictures during the local Harvest Festival, and he told us that: “I told them those photos wouldn’t go through censorship, but they wanted them anyway (…) I took the photos they wanted we sent them and one out of a hundred was approved.” He finished by explaining to us that eventually he learned how to do it the way the wanted it, thus again staying clear of any trouble and was able to live his life: “Nobody complained about me. It´s like that with every system. If you´re honest and work hard you´ll be okay in every system.”

He did specify though that the Second World War and the Nazi-regime was the worst one, since they didn’t allow him to attend school those years. This was the moment when it really occurred to us what this man had lived through and which changes he had experienced.

He seemed to have a very peaceful view on life in the past 85 years, which he summed up in a theory: “Everywhere in the world you have everything divided in half. Good and bad, smart and stupid. God and Devil. Crops and weeds. People are also divided, the good and the bad people. If you’re good, good things happen to you. If you’re bad and troublesome, you get bad things and trouble. If you´re not obedient, that’s when bad things happen.” This was not only the words of a very kind man, it was also clearly the words of man who from experience had learned how to get through life and still keep up hope.

Bridging Cultures: Mr. Chojnacki’s Endearing Family Tale

After we had asked all of our war-related questions, we decided to change the topic to something happier; family. We were especially interested of this part of his story as his wife is actually German! She lived in Olsztyn, where they met, but she belonged to the remains of the German minority who still lived in what was a former part of East Prussia. They got married 63 years ago and he still smiles while he talks about her or about the day they met, which we all found very adorable. He told us how she kept some of her German traditions and thereby creating a bridge between the two cultures.

This part of the interview was clearly filled with passion and love for his family and his hobbies. He continued to work as a photographer after the time of Communism and he had even brought some of his photos of the community and different families with to share – the first one he ever took was of course of his own family. Despite the absence of censorship, he said, with a twinkle in his eye that after he still knew how to do it the way people wanted.

Reflections on Homeland

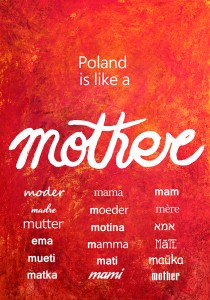

Poster Art by Bárbara Frases Rojas, Spain

To wind up the interview, we asked what Homeland meant for him, his answer was very thoughtful as he concluded: “Homeland is like a mother, there is just one” While we applauded him for his insight and sharing, his words had time to settle and we all looked at the person sitting next to us with a, “well that was both unexpected and beautiful!” look on our face. Just when we were about to start an internal discussion in English, Mr. Chojnacki looked at us and said:

“I’m very interested that YOU are interested in these topics. And I’m very interested in it because you belong to the good group who´s interested in history and you want it from a living man. This impresses me.”

Mr. Chojnacki and the group in front of his old photo shop (Photo: Tina Gotthardt)

Never had we felt more proud or grateful; to be told such words from an old man, who had lived through different wars and seen his country and the world change. It was definitely an honour to both be told such things, but also to have him share his life and memories with us and we gladly walked him home in the afternoon sunlight.

A Stroll Through Village Life in Poland

Photo: Tina Gotthardt

Even though we spent the day travelling through time, in the real world it was in fact only late afternoon. Therefore, we decided to take a walk around the little village to get an impression of life in the country in Poland. There was a very calm atmosphere as we walked around in the little streets; a combination of beautiful nature in the form of small lakes and gardens mixed with poorly looking houses and roads that had no asphalt on them. We walked through a small forest, passed a charming little castle and came down to a new-laid park, where a big celebration of the fire brigade was happening. We went down to get a closer look and it turned out to be a lovely festival filled with happy children and music, all celebrating the fire department.

The Role of the Fire Department in Rural Poland

Photo: Bárbara Frases

One of our councillors told us that in this town, and in general for most villages in the countryside, the fire department does not only put out fires, they also take care of and arranged activities for the children which created a strong communal bond something I found very encouraging with Mr. Chojnacki’s words about a strong community and worries about today’s society in mind.

It was finally time to walk back to the bus and drive home. Little was said during the drive home, where discussions of the day’s experiences were quickly replaced by the sound of deep sleep – probably dreaming about dinner and processing the important interpretations of the day.

This interview was conducted during the 2nd Baltic Sea Youth Dialogue in September 2015 in Olsztyn, Poland. You can see more results, like photos, posters, videos, in the virtual exhibition balticeye