Have you ever stumbled across an object that is not noticeable at first glance and wouldn’t appear out of place but upon closer inspection is quite unusual? And have you asked yourself what exciting, moving or sad story might be behind it? When our author Phillip encountered such an object, he began looking for traces in archives, history clubs, parish offices and town halls. After almost two years of research, he had uncovered a story about forced labour, post-war experiences, isolation and faith.

The strange gravestone

After my grandparents passed away a couple of years ago, I have been regularly visiting the local graveyard in my hometown Wolfhagen (North Hesse). One day, a very special gravestone caught my attention. Not only was it nearly hidden in the bushes and bore no name, it was also shaped like an Orthodox cross, which is unusual here since there is no Orthodox Church in Wolfhagen. Nevertheless, the tombstone itself is so inconspicuous that I didn’t notice it for a while, although there is a side entrance right next to the stone that I used a lot. I was curious about the story behind this gravestone, but lost sight of it at that time.

In 2019, the situation changed. While I was working for History Campus I realised that the unnamed gravestone could be the starting point for a journalistic story. Furthermore, as part of my history studies I had done an internship at the nearby Arolsen Archives, which reminded me of the horrible atrocities committed by the Nazi regime. One of them was the abduction of millions of people from all over Europe to Germany as cheap labour. These forced labourers not only lived in huge camps, but also in almost every village as farmhands. Although I didn’t know at the time whether the story of a forced labourer was connected to the tombstone, I suspected something along those lines.

First steps

Entrance to Wolfhagen’s “Heimat- und Geschichtsverein” (local history society), located right next to the local castle. (Photo: Phillip Landgrebe)

My first step was to contact the pastor who is chairman of the cemetery committee. But the pastor, being new to the job, had never heard of the gravestone before. My second step was a visit to the local history society, which proved more productive. The very helpful members informed me that there was already some small article about this case, published in one of their history volumes. And indeed, the person commemorated by this gravestone, Gabriel Kulczycki, was connected to the Second World War (WWII).

Contrary to what I expected, his story turned out to be a lot more complicated. Gabriel did not die during WWII, but in 1961, after he had already lived in Germany for almost 20 years. The article did not reveal exactly when he moved to Wolfhagen, but it must have been shortly after the war. Unfortunately, the authors of this article, who were both already deceased when I started my research, did not know much about Gabriel at all even though they lived in the same town. His name, nationality (Ukrainian), date of birth (1897), profession (farmhand) and date of death seem to be the only reliable information. Everything else is based on rumours and observations the town people made of their mysterious neighbour.

A short biography of Gabriel can be found here.

Gabriel the Nazi collaborator?

Apparently, Gabriel was a social outsider with very limited knowledge of German and therefore had hardly any friends in Wolfhagen. He was known for his unusual way of dressing as well as avoiding people because of his paranoid suspiciousness and hence spending most of his time with animals, which made him the target of ridicule by local children. As if that wasn’t enough, he became unable to work in the late 1950s due to dementia and moved to a shack. After his health deteriorated drastically, Gabriel was finally transferred to a psychiatric hospital, where he died shortly afterwards.

Volga Tatars in the Wehrmacht. The photo was taken between 1942-1944 for propaganda purposes. (Photo: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1995-043-14 / Philipps / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Most surprising for me was the fact that it was not clear to the authors why he moved to Germany in the first place. What seems to me a rather wild guess was that he could have been part of the Idel Ural Legion, which is a volunteer Wehrmacht unit recruited from ethnic minorities in the Soviet Union, and hence avoided moving back because he feared punishment. Since they offered no explanation why Gabriel, who was born in Western Ukraine, would have joined a military unit composed from mainly Turkic peoples from the Volga region, nor did they give any proof for this thesis besides rumours, I became very suspicious. Obviously, the local population had done little to understand the situation of this isolated person, but rather sought simple explanations.

Researching

The case started to fascinate me, and I decided to continue researching. What happened next can hardly be described as a single research process but rather a lot of small leads that I followed, all of which were related to my overall goal of learning more about Gabriel’s life and the history of his tombstone. When I write about it now, it may seem as if I had a clear plan from the very beginning. That was not the case most of the time. And even when I did, it was solely for individual sections.

This also means that my research can best be described as non-chronological and incomplete. There were times when I waited for an answer for several weeks. At other times I received replies from multiple institutions within a few days. Even right now, nearly two years after my first visit to the history club, there are still some enquiries that I hope to get feedback from and that may reveal new insights into Gabriel’s life. What I found so far is a fractured yet mesmerising biography of a person whose life was shattered in WWII and never went back to normal in post-war Germany. In addition, my research has become a story that is worth telling.

You can find more information about researching in German archives here.

Arolsen Archives

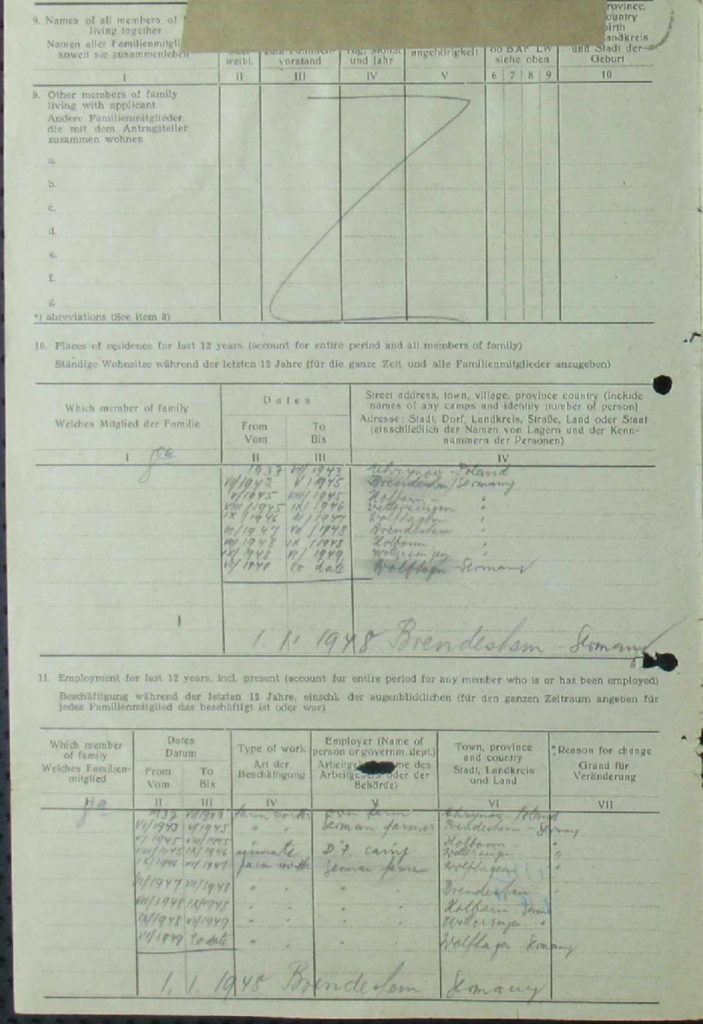

The story of this paper chase should probably begin with the most important find of the past months: Documents proving that Gabriel Kulczycki was a forced labourer. It was the Arolsen Archives which confirmed my presumption and played a crucial role in this story. After all, the papers they provided contain not only a so-called CM/1 file but also lists of former forced labourers from the Wolfhagen area.

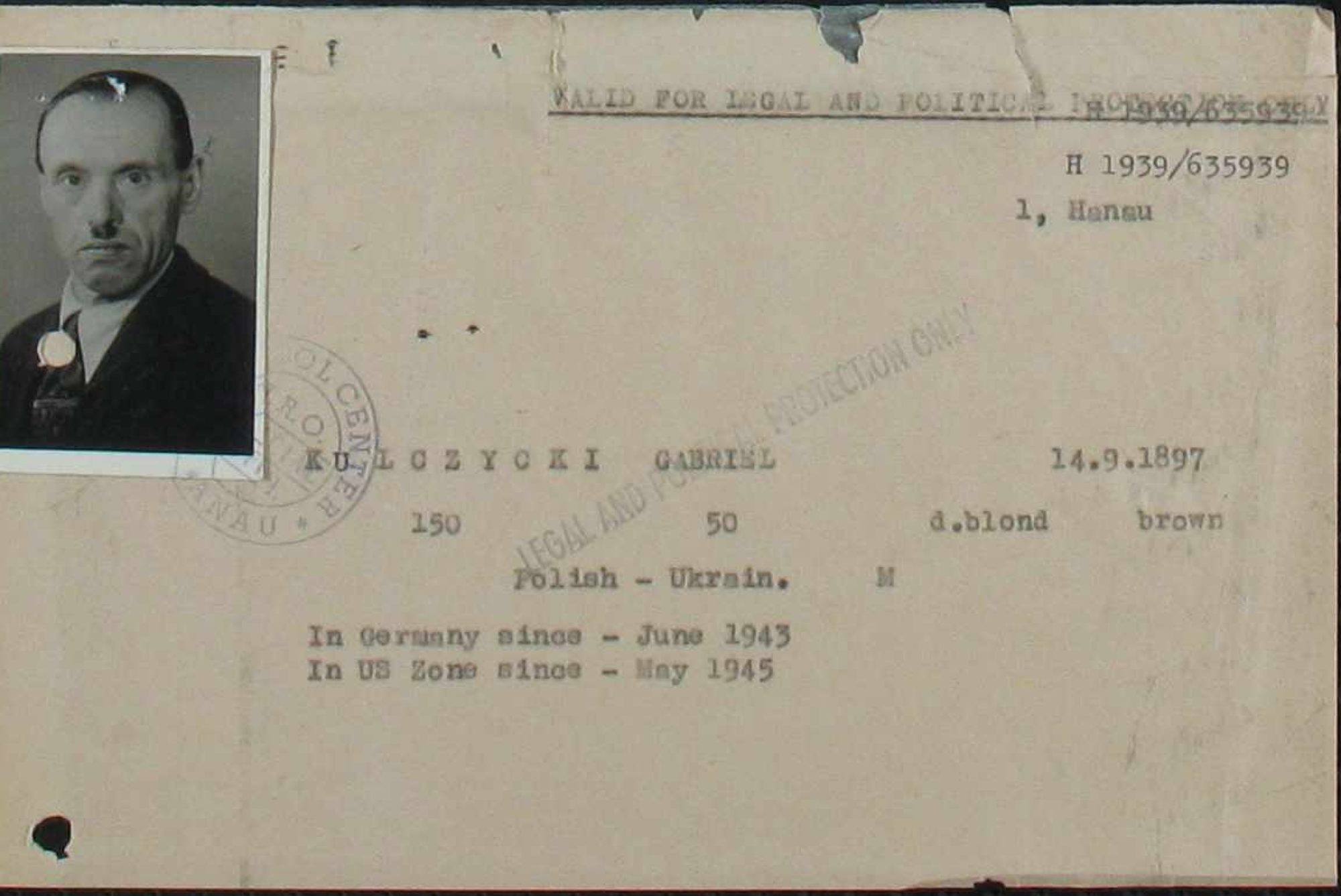

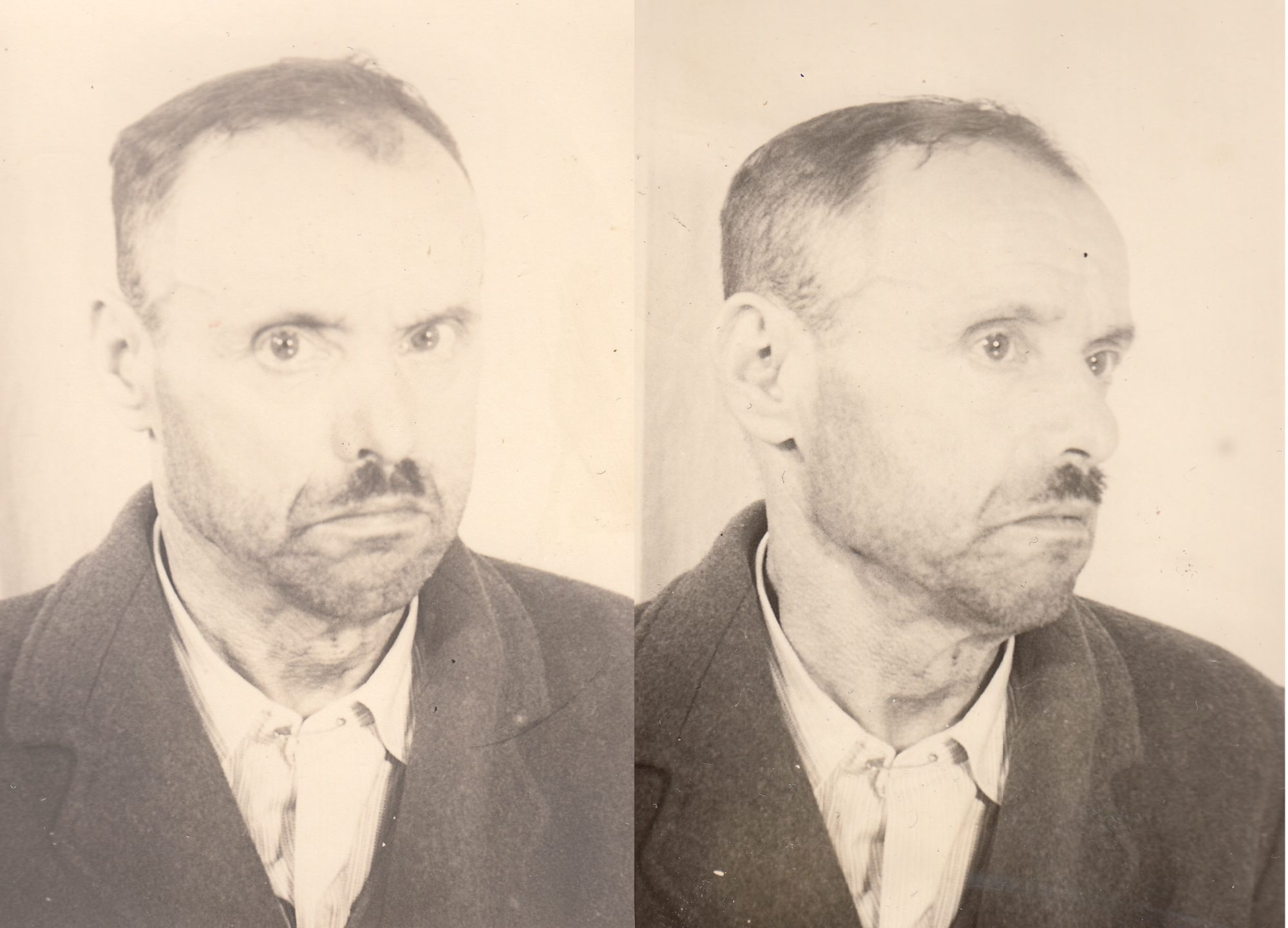

The first picture of Gabriel that I ever saw was in his CM/1-File. (CM/1-File Gabriel Kulczycki/ 3.2.1.1 /79359539/ ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archive)

The thesis of Gabriel having been a forced labourer is thus supported from two directions. First, there is a report with the CM/1 file, in which he tells interviewers of the International Refugee Organization (IRO) his story in 1949 and gives information about his time and whereabouts in Germany. His goal was to gain support from the IRO, and the fact that he eventually got it shows that his case was considered trustworthy. Second, there are lists collected by the Allied Forces with names of all foreigners in Germany during WWII. These lists had to be drawn up by German institutions, communities and companies and gave the Allies knowledge about the fate of prisoners of war, forced labourers and refugees. The fact that Gabriel is listed here means a lot, since they were created under the threat of penalties and should therefore not be seen as minor evidence.

Insights from the CM/1 File

At the same time, the CM/1 file provides some background details on Gabriel’s experiences as a forced labourer in Germany but has a much greater focus on basic personal information and his situation in 1949. One can see, for example, that despite his orthodox gravestone, he was a member of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, that he had never attended school and was therefore unable to write (his signature are three Xs) and that he was fluent in both Ukrainian and Polish. However, for the most part I only have vague names of the places where he was forced to work. Moreover, the place names were spelled incorrectly by the English-speaking interviewers and often left me at a loss.

A short info box about the Arolsen Archives is here.

Forced labour

A propaganda poster for recruiting civilian workers from occupied Poland. The caption reads: “Polish women and girls on their way to work in the Reich. Their joyful expectation will not be disappointed”. (Photo: Public Domain)

But what does ‘forced labour on farms’ during WWII actually mean? Apart from the fact that forced labour is always a violation of human rights and personal freedom, very heterogeneous forms of living and working conditions can be identified. Ethnic, national, religious, gender-based or political groups were assigned completely different legal statuses and thus scopes for action. This begins with the fact that forced labourers can roughly be divided into foreign civil workers, prisoners of war and (concentration camp) prisoners.

Diverse Legal Statuses and Living Conditions

If one takes a closer look at the group of civil workers, it must be noted that it is also not always possible to speak of forced labour. Especially in the early days of the occupation, the Germans tried to lure workers from Western and Eastern Europe into the Reich through massive advertising campaigns. It is interesting in this context that the term ‘forced labourers’ does not occur in the legal practice of National Socialist Germany. Rather, the illusion of a proper employment relationship is created without addressing the vast involuntary nature of the work. However, since the needs for workers could never be met by volunteers, the occupiers quickly moved to drive labourers to Germany through economic pressure on the occupied territories or arbitrary deportations. What was initially solely practiced in Poland and Eastern Europe became part of everyday life in almost all occupied countries at the end of the war. In addition, it was entirely possible to come to Germany as a ‘volunteer’, only to find out that the local authorities had no intention of adhering to the previous agreements or letting workers return home after a certain period.

Ostarbeiter

Not all foreigners were treated equally badly, which was partly due to the racist ideology of the Germans, but also due to political reasons during the war. For example, workers from states allied to Germany, such as Croats, Slovaks and (until 1943) Italians, even had a few privileges when it came to negotiating with employers and changing workplaces. Polish and Soviet citizens, on the other hand, had practically no rights, the latter being the so-called ,Ostarbeiter’ (Eastern workers) who suffered most severely from ill-treatment and discrimination. Of the more than 13 million forced labourers who worked in Germany between 1939 and 1945, they make up the majority and had the highest mortality rate.

Working on farms

With the drafting of many male agricultural workers into the Wehrmacht, there was a continuous need for farmhands in the Reich during WWII. The recruiters thus tried to attract experienced and healthy farmers to work in Germany. After arriving to the Reich, the foreign workers (which usually came in groups from the same area or village) were separated, often regardless of family or friendship, and distributed to larger granges or smaller farms as needed. As a result, some of them lived on manors with several hundred other forced labourers while others were the only foreigners in little hamlets or resettlers’ yards.

Diversity in Farm Labor During WWII

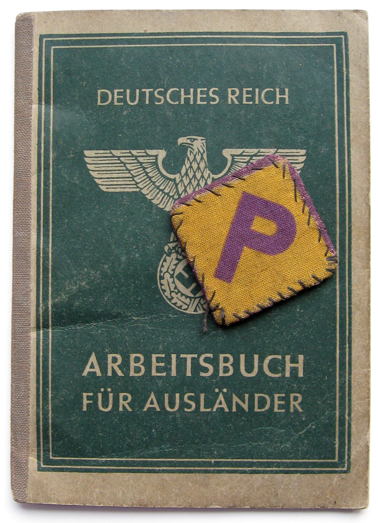

“Arbeitsbuch für Ausländer” (Workbook for Foreigners/Identity document) with a P-patch identifying a Polish forced labourer. (Photo: Sjam2004, CC0 1.0 license)

Poles, who came to Germany early as 1939, were the first group to increasingly work in agriculture. This was balanced out in the course of the war by the arrival of, among others, Soviet workers. The lives of Poles and Ostarbeiter in particular were restricted by a large number of discriminatory rules. For example, they were not allowed to eat at the same table with their German bosses and co-workers. This also applied to leisure activities that were characterised by strict surveillance of both Poles and Ostarbeiter. In contrast to Western Europeans, they even had to wear labels on their clothing that identified them as members of these two groups, drastically limiting their options of what to do in their free time. There wasn’t much free time anyway on farms where people worked from sunrise to sunset. In addition, even though many German men joined the army, the authorities demanded that every agricultural holding met their delivery target – this gave farm owners an incentive to exploit the most unprotected groups among the forced labourers to the fullest. Living and working conditions of the forced labourers were therefore much determined by their German bosses, who could either make small improvements in their everyday life or have them mercilessly toil to the bone.

Research Challenges

If we want to break away from this rather general characterisation of forced labour in agriculture and look at the specifics in North Hesse, a problem arises: There is no systematic research on this. While there are many papers about the working and living conditions of forced labourers in large or not so large companies of Hesse, I was only able to find small notes, sometimes just sentences, about the situation on farms in my area. The state of research on North Hesse thus reflects a general problem in the analyses of forced labour, namely that the industrial sector has received a lot of attention, whereas forced labour in agriculture has been researched well in only a few cases.

Stories of friendship between Germans and forced labourers?

Since university research does not help here, it is essential to turn to the work of the many small history societies in the region. As I indicated earlier, these clubs often publish their own writings by committed members with good connections within their communities. The advantage of these papers is that they were mostly created in close cooperation with contemporary witnesses to National Socialism and thus contain first-hand information. The disadvantage, however, is that they were exclusively German or at least German-friendly contemporary witnesses. This creates a simple pattern which I observed best in the history books from my home town: Good coexistence between the local population and forced labourers, especially friendships that have arisen in the process, is often mentioned, while dark sides are usually left out or are connected to people from outside the community.

Harmonious coexistence? A group photo during the war years in front of the house of the Löwenstein baker family in Wolfhagen. On the far left is master baker Wilhelm Löwenstein, next to him is French prisoner of War Maurice (or Marcel) Linard. Linard was in Wolfhagen until summer 1946. The context in which the photo was taken is unknown. (Photo: Unknown. Property of the Heimats- und Geschichtsverein Wolfhagen)

Examining Biases in Local History Accounts

Why am I emphasising this? These books contain information about how German farmers treated ‘their’ forced labourers nicely, giving them extra food or ignoring orders to separate them from family dinners. Even the few reports by actual former forced labourers tend to highlight the good coexistence with the local population. An interesting record is, for example, a roughly four-page report by a Russian woman, annexed to a volume about the year 1945. She married her former boss in 1948 and stressed how much her employer and his family helped and protected her during the war. Accounts of brutality or malnutrition of forced labourers can hardly be found in these books or are hidden in partial sentences. But minor remarks like that one about a local watchman, who “had not treated the Poles with kid gloves”, take on a whole new quality, considering that according to the lists of the Arolsen Archives at least one Pole committed suicide in Wolfhagen. It can be assumed that this is only the tip of the iceberg.

The case of Wettesingen

Entrance of the Rittergut Wettesingen, the grange where Gabriel lived as a forced labourer. (Photo: Phillip Landgrebe)

In addition to the danger of harmonising the past, these societies have another major problem, as I would like to demonstrate by using one of Gabriel’s few workplaces that I could clearly identify as an example. It is a grange in Wettesingen, a village in the old district of Wolfhagen that had only 891 inhabitants in 1939. Using data from the Arolsen Archives, I can say that Gabriel worked on this farm with about 31 other forced labourers from Russia, Poland, Italy, the Netherlands and Serbia. No less than 50 more (of various nationalities) were accommodated in other parts of the village. Looking at these numbers, the local population must have interacted with the foreign workers in some way.

But when I contacted the local history society, I learned that they had almost no information about forced labourers in Wettesingen. To put it more precisely, a friendly member informed me that forced labour has not even been an issue in their club yet. Paradoxically, I wouldn’t say that this is because of malicious intent. Since no one from outside apparently ever asked a question about forced work in the village, it may never have become a relevant issue for the village population itself. However, this also means that the historical societies, which are often the only ones that ask questions on a topic that has so far been avoided by academical research, have a lot of blind spots. Knowledge about living conditions or fate of forced labourers in rural areas is inevitably lost if there is no effective work-up at the local level.

A forced labourer from West Ukraine in North Hesse

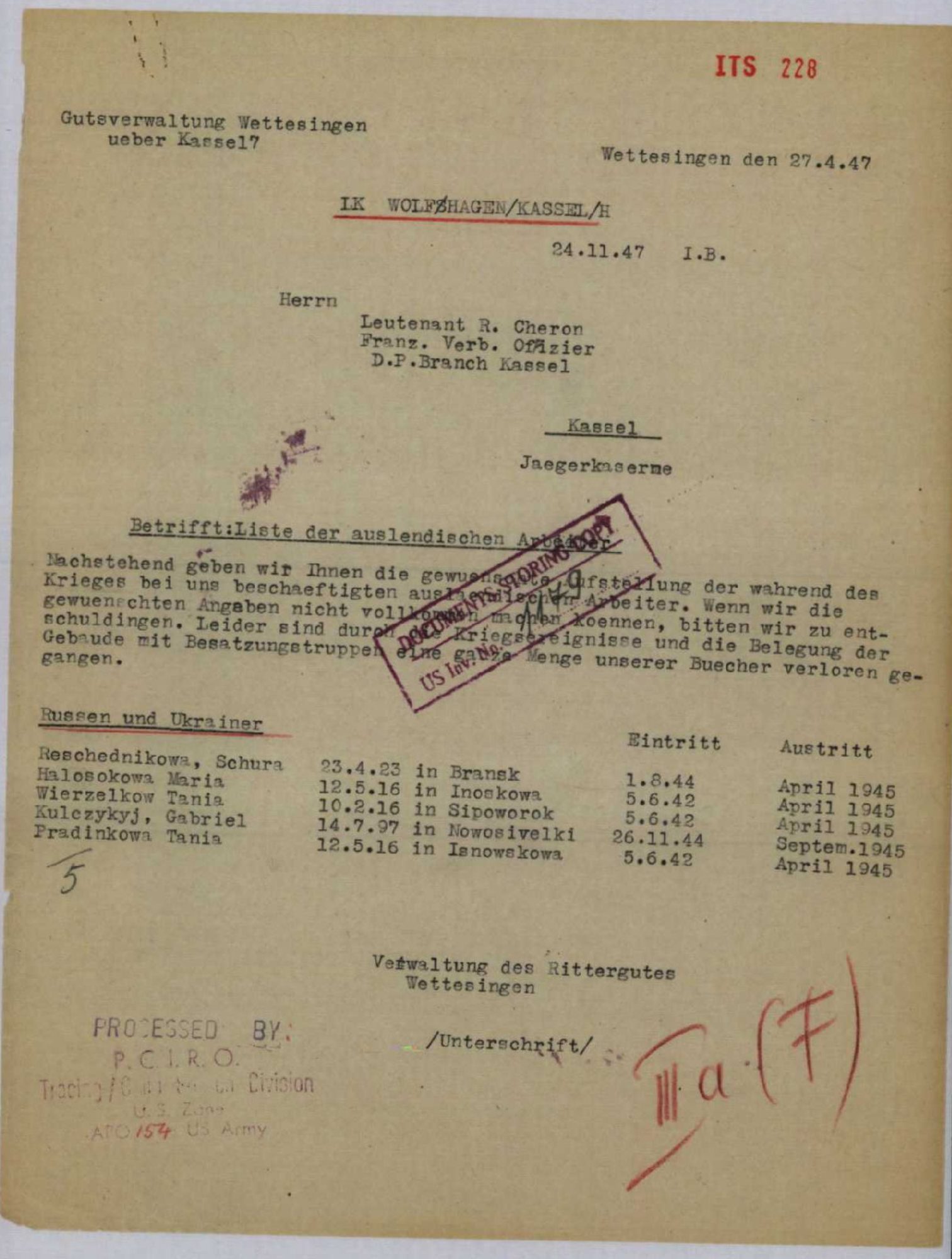

Post-war list of Russians and Ukrainians working on the Rittergut during WWII. (Liste ausländische Arbeiter Rittergut Wettesingen/ 2.1.1.1 /70484206/ ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archive)

So, even if I can’t say much about Gabriel’s life in Wettesingen, his nationality and the general circumstances of its employment allow a few cautious conclusions to be drawn. Although Gabriel had spent most of his life as a Polish citizen before being deported, he was a Western Ukrainian and had a therefore relatively privileged position among Slavic forced labourers. In comparison to Serbs, Russians or Poles, it is possible that he got a bit more money, days off or medical care. This is because Galicia, a historical region in Western Ukraine was part of Austria-Hungary until 1918, and the Germans expected a more sympathising attitude of the population there when invading in 1941.

Still, in the eyes of the Germans he was an Eastern European and therefore inferior from a racist perspective, which means his treatment must have been worse than that of the Dutch workers for instance. In addition, the accommodation together with a larger group of forced labourers is to be assessed ambivalently: He was not at the mercy of a single German family as were those civilian workers who were individually housed on remote farms. However, less contact with German employers or co-workers meant fewer opportunities to receive support or protection from them. It also plays a role that Gabriel changed workplaces several times for unknown reasons and lived in all those villages for just a short period of time. Lasting friendships with other forced labourers or Germans, as they are well documented in other cases, were difficult to establish and maintain in this way.

Liberation

On March 31st, 1945, American troops entered the town of Wolfhagen and the surrounding villages. For hundreds of forced labourers in the area, this finally meant liberation from the cruel enslavement that the Germans had forced on them. Gabriel, who was still on the grange in Wettesingen, must also have been freed around this time. In the depiction of regional historical works, though, the image of forced labourers’ changes with the liberation fundamentally. Previously, they were the pitiful and exploited people by the NS-Regime (who the warm-hearted local people took care of), but all the sudden they became violently vengeful looters and robbers.

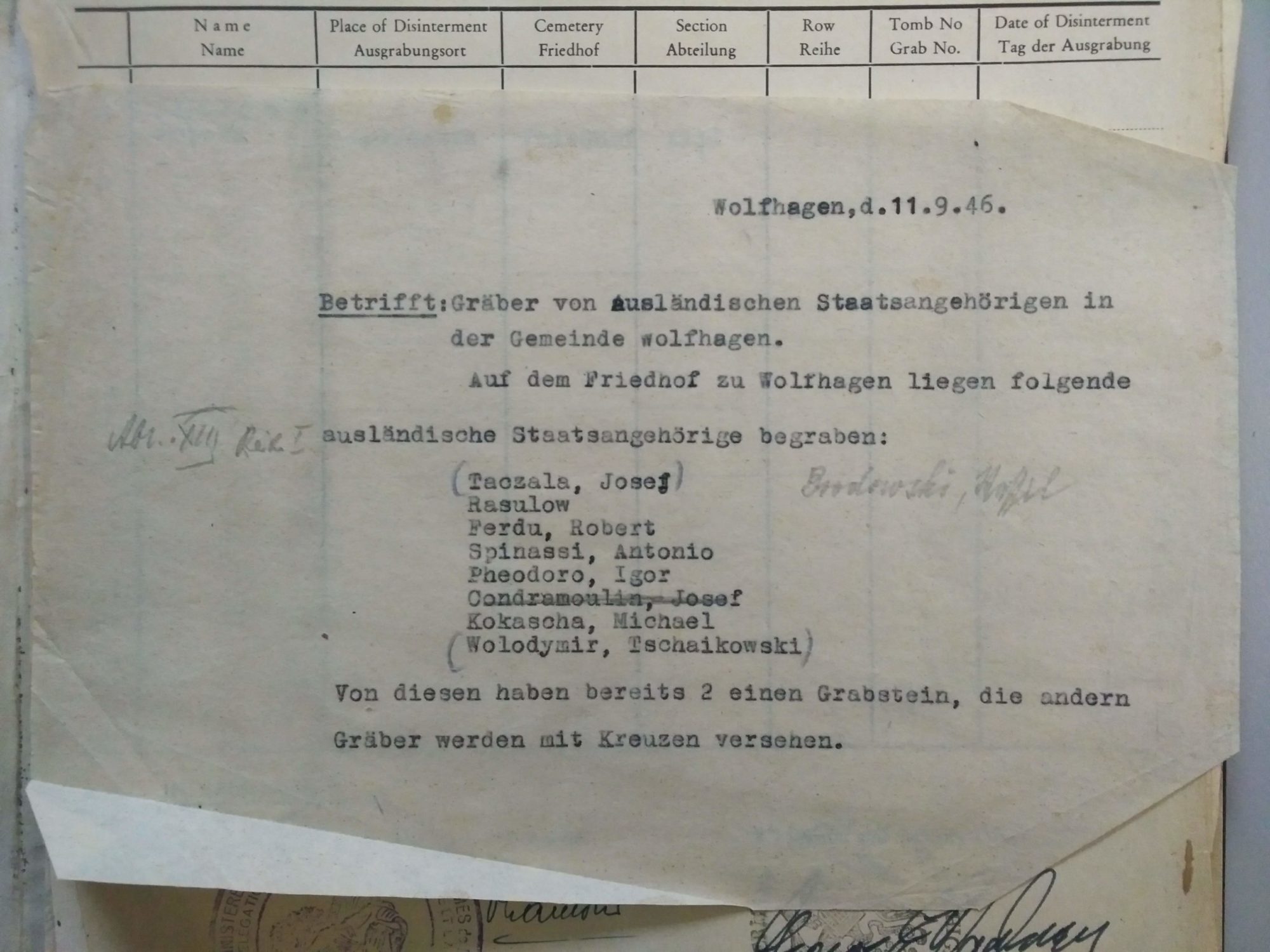

Names of the foreign workers/forced labourers who died in Wolfhagen until 1945. (Alphabet. Namensverzeichnis über die auf dem Friedhof der Stadt Wolfhagen ruhenden Toten, die bis zum 12.12.45 einschl. verstorben sind/Landeskirchliches Archiv Kassel, D 2.2 Wolfhagen v.O. 646)

The murder of two Wolfhagen citizens by a group of Poles in April 1945 is often mentioned in this context. But little information is given about the experiences of the liberated workers in the immediate post-war time. An interesting testimony for this is the death register of the Wolfhagen cemetery. It shows that six of the nine foreigners, who were buried in the town between 1942 and 1945, died in March, April and May 1945. Most deaths occurred directly before or shortly after liberation. With the help of various post-war German documents from the Arolsen Archive, even the leading cause of death can be identified: pulmonary tuberculosis. Assuming that these documents are to be trusted, the situation of shelter, nutrition and medical supply of forced labourers must have reached a horrible low between March and April.

Post-Liberation Challenges

The number of foreigners who died in Wolfhagen is comparatively small: over 700 former forced labourers lived in the town at the end of May despite some early repatriations in April. Still, the experienced lack of supply could have been a plausible reason for acts of self-procurement. In addition, violence was not only directed against Germans. Seven weeks after his liberation, a Russian perished after suffering fatal gunshots to the head. It is unclear who fired these shots, but it does make it clear that the post-war period was also dangerous for the liberated forced workers.

Why did Gabriel stay in Wolfhagen?

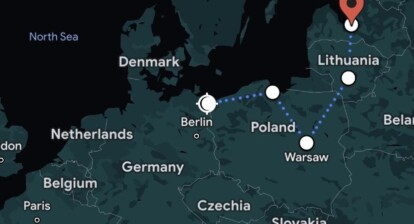

The list of Gabriel’s whereabouts between 1937 and 1949, with a special focus on the time in Germany from 1943. It is striking that he never stayed in one place for long. (CM/1-File Gabriel Kulczycki/ 3.2.1.1 /79359539/ ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archive)

Why then did Gabriel decided to stay? This question is not easy to answer. His CM/1 file shows that he had little interest in continuing to live in Germany. Also, he does not appear to have had permanent accommodation or work in the first years after WWII. In fact, Gabriel stated that from 1945 onwards he had moved back and forth between Wolfhagen and the surrounding villages, apparently working on the farms he knew from his time as forced labourer. In later documents there is a remark about his former workplaces that at some point “there was no place to sleep anymore”. Only in 1948 he managed to get a stable employment by a Wolfhagen farmer where he worked until the 1950s.

The sole explanation I could ever find from him on this question is also from the CM/1 file, in which he claims to still be waiting about news from his family. Nevertheless, neither the file nor any of the other documents from that time provide any information as to whether he was married, had children, or was looking for his parents or siblings. There is also no evidence that he later had any contact with his relatives in Ukraine.

Western Ukrainians and ‘repatriation’

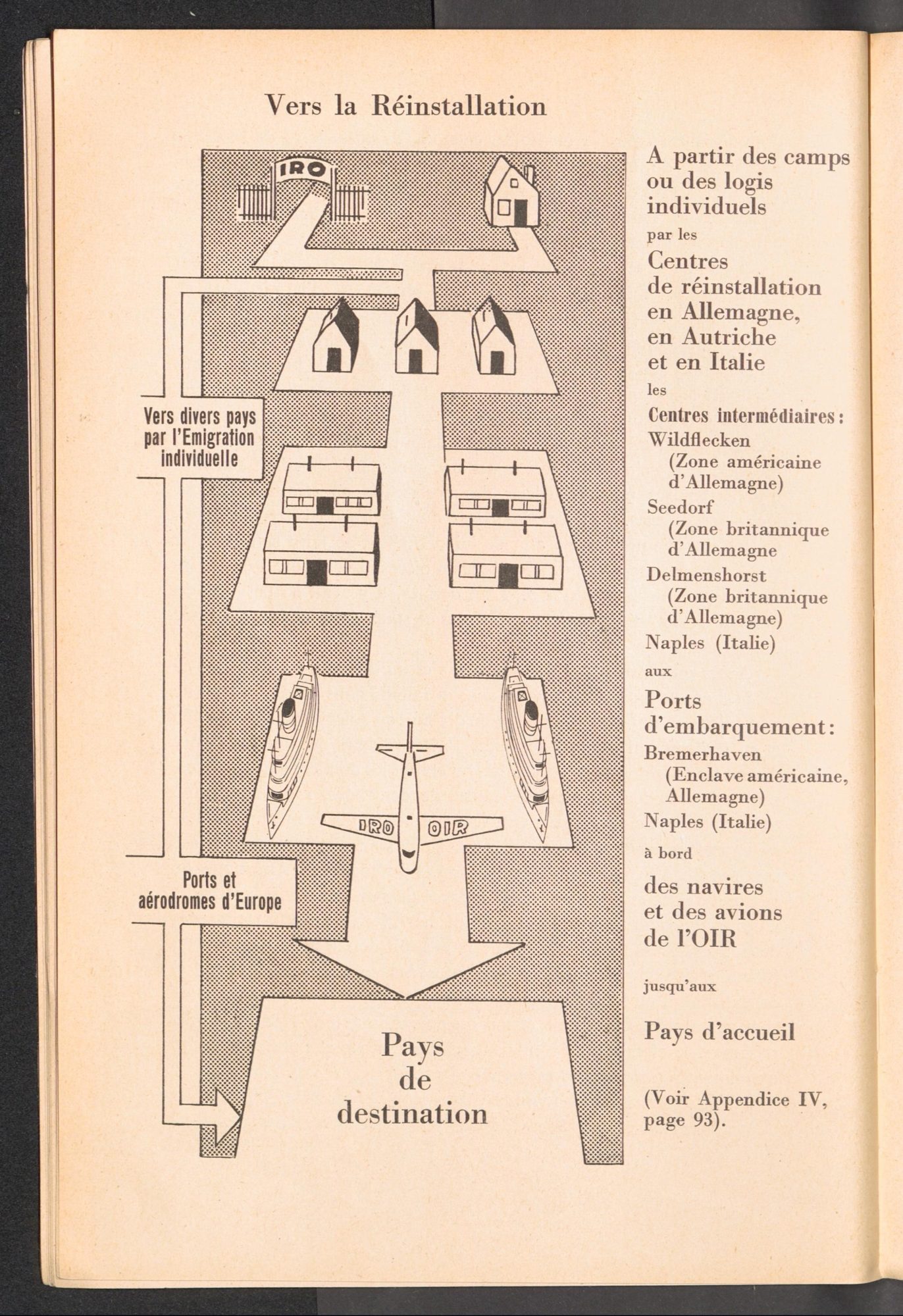

Info graphic from a French booklet about IRO resettlements in 1948-1949. (Photo: Rapport du Directeur Général au Conseil Général de l ‘Organisaton Internationale pour les Réfugiés: 1 er juillet 1948 – 30 juin 1949/ Organisation Internationale pour les Réfugiés (OIR)/ Genf 1949/ ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archive, p. 40)

His hesitation ‘to return’ may also be explained by the question of where he could go back to. As a Western Ukrainian, he was a Polish citizen until 1939. However, his home was finally incorporated into the Soviet Union at the end of the war, a country in which former forced labourers were stigmatised as being alleged helpers of the Nazi regime or even detained in special camps. Research suggests that only about 42% of Western Ukrainians ever returned to their hometowns, while over 80% of forced labourers from the Soviet Union (including Eastern Ukrainians) made their way home. This may also be reflected in the fact that the Western Allies already in 1946 ceased to implement the forced repatriation of Soviet citizens, which was demanded by the Soviet Union, since many ‘returnees’ resisted strongly and suicides occurred again and again.

Post-War Dilemmas and Difficult Choices

At the same time, though, many Western Ukrainians did not stay in Germany, but used the so called resettlement program to emigrate to various Allied countries. Those who stayed behind often did so out of fear of another rapid change in their living conditions, although the Allies massively advertised a new start abroad among the former forced labourers. Why Gabriel ultimately decided not to emigrate is unclear, but the paranoid suspiciousness attested in the article about him may well have had a real background. After all, the Ukrainian had been subjected to abduction by force, exploitation to the bone and the insecurity of impending forced repatriation, so he probably had not much confidence in new political programs. His age (he was 52 in 1949) could also have played a role, since the receiving countries were primarily interested in younger workers who still had a large part of their career ahead of them. This made Gabriel one of the approximately 280,000 ‘heimatlose Ausländer’ (uprooted foreigners), as German officials called the displaced persons (DPs), who remained in Germany permanently but never really became part of German society.

Uprooted Foreigner

I wish I could write something about how Gabriel’s life as an ‘uprooted foreigner’ looked like. Did he really not have a single friend, as the article mentioned in the beginning of my research suggests? Was he the only former forced labourer in the region or were there maybe others to talk about their experiences? And why did he stay at the same place where he had been forced to work hard a few years earlier? Unfortunately, there are no written records about Gabriel from the 1950s to answer these questions. After all, he lived an inconspicuous life as a farmhand in a small town that considered him a strange outsider, but otherwise didn’t pay him any attention. The reason why Gabriel appears in written documents again has to with his dementia and the year 1961.

Pictures of Gabriel, taken in Haina shortly before his death in 1961. (LWV-Archiv Kassel/ K 13/ Nr. 1961/078)

I discovered these documents at the State Welfare Association of Hesse after a few months full of dead ends. That’s why I was even more surprised when I found that the association not only kept old medical files from its clinics, like the one about Gabriel from the Haina psychiatric institution, but also that this file was more than just a pure medical account – it offered some insight into his life before Haina. The background of his admission to the psychiatric institution is particularly worth considering, as many details about his last months have only been recorded there. These records shed light on the status given to ‘uprooted foreigners’ in post-war German society.

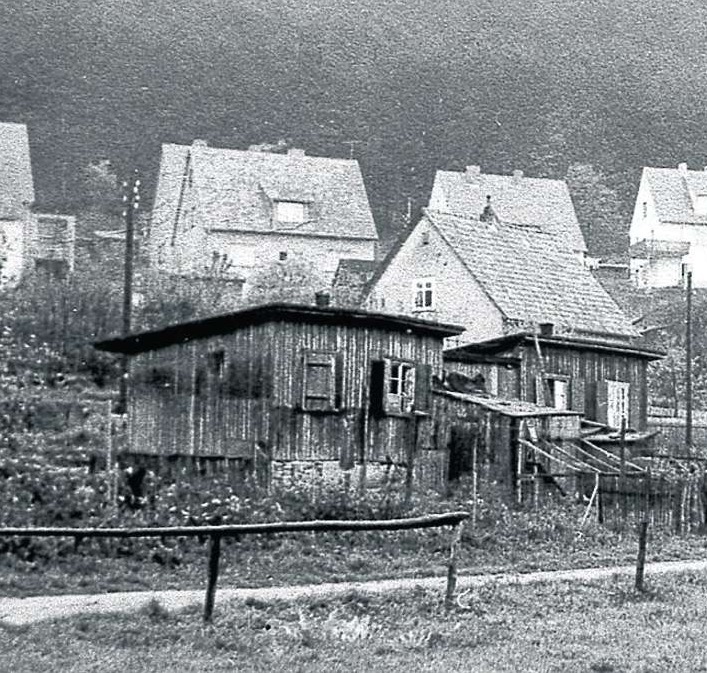

A makeshift shack in 1961

Post-war shacks in the street that Gabriel lived in until 1961. (Photo: Rudolph Killian)

At the end of the 1950s, Gabriel lived in a small wooden shack with two rooms that the town originally had built for refugees after the war. Since he was already unable to work due to his illness, he received a small pension and otherwise lived largely reclusively. This changed in March 1961 when he was suddenly assigned a legal guardian, Maria Ruschmann, and at the same time was removed from his shack. The official reason given was that Gabriel was no longer able to live alone because town officials had found him and his home in a neglected state. However, the fact that the last of the post-war shacks was planned to be demolished at this time, leaving no place for Gabriel to live, could have also played a role in his removal. This assumption would be supported by the fact that there is no evidence that his condition had interested anyone before 1961.

The Enigmatic Eviction: Unraveling the Circumstances Surrounding Gabriel’s Removal and Placement in 1961

It is fairly certain that Gabriel did not agree to the eviction. Nor does he seem to have liked the transfer to a special-care home close to Haunetal (a good 80 km from Wolfhagen), which was organised by his guardian Ms Ruschmann. His dislike is evidenced by the fact that Gabriel returned to Wolfhagen independently in early April. There he was admitted to the local hospital due to some health conditions, where members of the hospital staff claimed to be overburdened with the treatment of Gabriel (who was now seriously demented) and considered treatment on site to be impossible. Although he insisted several times to stay in Wolfhagen, the district court acted promptly and had him admitted to a secured ward in the Haina psychiatric institution less than two weeks after his return. This swift ruling even surprised Ruschmann, who found out about it only after Gabriel’s transfer to Haina and immediately protested against the decision.

Haina psychiatric institution

However, it quickly became clear that in Gabriel’s case there was no alternative to intensive care in a secured clinic. In addition to his dementia, the official list of his medical problems at the time of his death also included heart failure, kidney damage, bronchitis and rheumatism. It is thus no wonder that Gabriel, who was slowly dying, must have been in great pain, although the staff tried their best for almost two months. Ruschmann hence accepted Gabriel’s admission to Haina after paying a visit to the clinic.

A dormitory in ward VI of Haina psychiatric institution in the 1960s. Gabriel was placed in this ward, but it is unknown in which room. (LWV-Archiv Kassel/ F 13/ Nr. 1385)

This visit is particularly interesting for the research, because Ruschmann gave some statements about Gabriel’s background that are preserved in his file. Since she stated to have interpreted for Gabriel, which means that she could speak to him in either Ukrainian or Polish, she might even have heard his life story in his own words. For example, she told the staff that he was “chased like rabbits across the field” in his home country. Later, his long-time employer in Wolfhagen is said to have only taken advantage of him. She also had nothing good to say about Wolfhagen Hospital, which according to her treated Gabriel badly after he was taken in with cardiac asthma and kidney problems. There are limits to Ruschmanns knowledge, however, which can be seen when she suggests that he may never have received wages from his employer, although the CM/1 file does show monthly earnings in 1949.

Deciphering Gabriel’s Final Days

While the care worker’s words were taken seriously, Gabriel’s own explanations and requests were seen as unreasonable and stubborn. This applies to conversations he had with members of staff, but also his interview records from the district court that appear to have been sent to Haina as well. Since he was a seriously demented patient who had shown strange and unhygienic behaviour in his last weeks, this may have been justified from the point of view of staff and officials. At the same time, his statements perfectly display what was important to Gabriel shortly before his death: He, for example, not only repeatedly expressed his wish to return to Wolfhagen, but also explained that “all of his acquaintances” were there – a rare indication of his social environment in Germany. His greatest wish, though, was still to return to Ukraine, and for the first time he mentioned close relatives, namely a sister and a son, whom he was waiting to hear from. Because of the stories that were rife in Wolfhagen, it is moreover interesting that he claimed to have been a soldier for 10 years. But neither did his interviewers go into further detail on these assertions, nor did he continue to elaborate on it. Unfortunately, it thus cannot be determined whether this was confused talk or actual information about his life.

Roses in front of the gravestone

Who put the roses there? (Photo: Phillip Landgrebe)

The last phase of Gabriel’s life was tragic in two ways: Firstly, due to his illness and isolation, he lived in miserable conditions in his last years. Secondly, even though several local institutions realised that he needed help, they only wanted to get rid of him. Town officials, the hospital and the Wolfhagen district court complied with their legal obligations but did not show the slightest bit of understanding for Gabriel’s own wishes. Of particular concern is the fact that some of them were the same institutions that helped exploiting him during WWII. Voices that actively supported Gabriel can hardly be found, except for Maria Ruschmann maybe.

With this in mind, it is even more astonishing that right at the start of my research I found roses in front of his tombstone. Since I assumed that he had no friends or relatives in Germany, I was initially clueless from whom these flowers could be. Again, I contacted the pastor in charge of the cemetery, who suspected that Russia-Germans could use the tombstone as a memorial. In fact, there are many Russian or Ukrainian-speaking people in Wolfhagen who mainly came to Germany after the fall of the Iron Curtain in the early 1990s or are children of the original migrants. But why would they commemorate a person whom they couldn’t possibly know and who is unlikely to be related to them? And did they know the rumours that Gabriel was a Nazi collaborator? I decided to dig into this as well.

Migration and Wolfhagen’s Catholic community

The Protestant pastor recommended I enquire in the Catholic parish to get access to Eastern European migrants in Wolfhagen. It should be said that before WWII, in addition to the Jewish community that existed until 1939, when its last members had been deported or fled, Wolfhagen was primarily influenced by the Protestant Church. Only because of the influx of Catholic immigrants did a community with its own church emerge in the town. Since many of the migrants who moved to Wolfhagen after 1990 were members of the Eastern Catholic Churches, the local community experienced a second, strong boost during these years. As I learned later, it is mainly people with roots in Ukraine who shape parish life today.

Service at the Catholic church in Wolfhagen. (Photo: Phillip Landgrebe

A cordial member of staff at the Catholic parish office informed me that she didn’t know anybody who placed flowers at the tombstone. Nevertheless, she offered me the opportunity to present my request to the congregation during church service. The service was a strange and yet very positive experience for me. Compared to the Protestant services during the time of my confirmation classes, in which mainly some pensioners took part, there were not only significantly more people in the Catholic church, but also young families with children. When the priest finally called me forward, the people in the church were much livelier and more interested than in the services of my memory.

Bridging Faiths and Communities

As I presented my request to the congregation, the priest stepped in and assisted me in describing my research and the discovery of the roses. He then explained to me that Gabriel’s fate was particularly interesting for the community, since many of the parishioners came from one village in Western Ukraine. Unfortunately, this doesn’t seem to be the same area where Gabriel was born. In addition, the interest doesn’t appear to have been caused by previous knowledge of the gravestone. After the service, some visitors asked about my research or wished me luck. A very small group even let me show them the stone and promised to ask around about the roses. However, I could not gain any new information about commemoration at the tombstone that day and have not heard from the congregation since.

Why is his gravestone still standing?

Even the best strategy and preparation does not replace the findings that you make by chance. A good example of this is a conversation I had with a cemetery worker when I visited my grandparents’ grave. Originally, the pastor had informed me that he had interviewed the cemetery staff and that they did not know anything about the grave, since an elderly worker with a lot of knowledge about the graveyard had recently died. However, this worker knew a few stories that had been narrated to him by his predecessors. He told me that in the 1990s the tombstone was a symbolic memorial for Russia-Germans who sometimes placed up to 50 candles there on All Saints’ Day. Although this tradition has decreased considerably over time, he suspected that the roses were put down in this context. Commemoration at the gravestone is therefore not linked to Gabriel’s fate or forced labour in general, but rather served migrants to maintain symbolic ties with their old homeland and the memory of their dead.

Unexpected Discoveries

Did Gabriel’s gravestone look similar in the 1990s? All Saints’ Day in Gniezno, Poland. (Photo: Diego Delso, delso.photo, License CC-BY-SA)

But why is Gabriel’s tombstone still standing? According to the cemetery regulations, the rest period is 25 years, so that his grave should have been levelled around 1986, long before it received the symbolic status in the 1990s. The worker was also able to help here: Gabriel’s gravestone is not at his original burial place but was moved after the rest period. This means the exact location of Gabriel’s grave within the cemetery remains unknown. He also stated that the reason for the relocation of the cross was that it was “special” and hence kept. As there were no hedge or bushes on the cemetery wall at that time, the new place of the gravestone was clearly visible and, since there is a gate not far from it, by no means remote. In the absence of a map of the graveyard from the 1980s, I have no choice but to trust this explanation. At the same time, though, he couldn’t answer why the cross is still there today. Even if the new location of the gravestone was initially much less secluded, the height of the hedge and bushes indicate that it has been almost hidden for many years.

Open Ends

As with so many steps in my research, I have come to a point where, due to a lack of written records or knowledgeable contemporary witnesses, I cannot get any further. With that, my report on the life of Gabriel and his tombstone also comes to an end. After all the months of immersing myself deeper and deeper in the topic, it is frustrating how many questions remain unanswered and will probably never be resolved. For example, I still don’t know why his tombstone has no name. It also concerns me why the Catholic Gabriel received an Orthodox gravestone, although he may even have visited the local Catholic community in town. Unfortunately, I have no control over what is preserved and what is not. Sometimes, it seems absurd. While I know exactly how much the parish office charged for Gabriel’s funeral, and I even know how much putting him in his coffin had cost, I cannot say who paid for his funeral or commissioned the tombstone.

Unanswered Mysteries and Divergent Commemorations

The memorial for the fallen soldiers of both world wars from Wolfhagen is located very centrally on the cemetery. (Photo: Phillip Landgrebe)

What I also took with me from the last two years is how different commemoration can be. While the local population first kept the tombstone and then apparently almost forgot it, Eastern European migrants made the Orthodox Cross a symbolic monument in the 1990s without even knowing the history behind it. The handling of the gravestone was not always correct in my opinion: Above all, I have the impression that it was preserved more because of its exoticised ‘otherness’ than because of the extremely sad story that is behind the stone. Since even Wehrmacht soldiers are honoured on their own, very central part in the cemetery, there is no comprehensible reason for leaving the tombstone at its current location.

Unanswered Questions and Commemorative Reflections

Therefore, I would consider it an urgent need to move the stone from the corner, which does not even represent Gabriel’s actual grave, to a new, more visible place. Apart from Gabriel, at least nine other forced labourers were buried in this cemetery, who were not lucky enough to survive 1945 and there is nothing to remember them by. It would thus be great to honour the person associated with the cross and the subject of forced labour in Wolfhagen with a small memorial plaque. During my research I often have heard the vague comment that something should be done. My hope is the new knowledge about Gabriel may actually change something. In the meantime, I have noticed that from time to time new flowers are put in front of the cross. A beautiful sign that Gabriel’s gravestone will not be forgotten so quickly.

Gratitude and Acknowledgments

Over the past few months, I have been supported by a variety of institutions and individuals. Even if I cannot mention every single one of them here, I would like to thank the most important helpers at least briefly. This applies in particular to the Arolsen Archives Reference Services team, which was always quick and uncomplicated to assist me with my enquiries. But I would also like to mention Dr. Dominik Motz and the archive of the State Welfare Association of Hesse, without whom I could not say nearly as much about Gabriel’s post-war life. At the local level, I would particularly like to thank Gerd Riedemann and Dirk Lindemann from the Wolfhagen’s history association. The former for always taking time for my questions and supporting me to the best of his knowledge, and the latter for referencing literature and giving permission to use photos from his collection. Thanks also go to Gilbert Schmale from Wettesingen’s history association, who took the time to do a (unfortunately unsuccessful) search for information about forced labour on the grange. A big help were Martin Jung from the Protestant community and Simone Straka-Geiersbach and Marek Prus from the Catholic community, as well as the employees of the Wolfhagen cemetery who provided me with a lot of valuable information about the graveyard and religious communities. Finally, I would like to thank Helmut Rupp and Jan Fischer from the town hall Wolfhagen, who did their best to support my research despite the corona restrictions.

Nora Stalke

Sehr geehrter Herr Landgrebe,

vielen Dank für Ihre wundervolle Recherche zu dem Grabstein. Ich war zufällig an in unserem katholischen Gottesdienst, als Sie Ihr Anliegen vorgestellt haben. Wir haben danach einpaar Worte zu dem Fall gewechselt.

Es ist wirklich eine erstaunliche Geschichte, insbesondere im Hinblick darauf, wie gut sich der Lebensweg von Herrn Kulczycki doch nach so vielen Jahren rekonstruieren lässt. Auch in Anbetracht dessen, dass er keine Bekannte Persönlichkeit war.

Ich darf mir allerdings einen kleinen Hinweis erlauben: viele Mitglieder unserer katholischen Kirche, dazu gehört auch meine Familie, kommen aus der Ukraine. Um genauer zu sein aus der Region um Mukatschewo. Dies liegt zwar nicht in unmittelbarer Nähe zum Geburtsort des oben genannten Herren, jedoch auch nicht in einem vollkommen anderen Teil des Landes.

Sollten Sie jemals Interesse daran haben auch hier mehr zu erfahren, können Sie mich gerne jeder Zeit kontaktieren.

Ihr Anliegen, den Stein umzusiedeln und einen würdigeren Platz zu bieten, würde ich ebenfalls gerne unterstützen. Ich wünsche Ihnen voel Erfolg bei Ihren Bemühungen.

Phillip

Sehr geehrte Frau Stalke,

ich danke Ihnen sehr für Ihr Lob!

An den Gottesdienst kann ich mich noch sehr gut erinnern, da er, wie im Artikel geschildert, eine sehr positive Erfahrung für mich war. Tatsächlich hatte mich Herr Prus bereits an dem Tag auf die besondere Verbindung der Gemeinde zur Westukraine hingewiesen. Auch kann ich mich an einige Interessent*innen an meinen Recherchen erinnern und freue mich, dass Sie den Fall nach wie vor aufmerksam verfolgen.

Mich würde immer noch brennend interessieren mit Personen zu sprechen, die Blumen oder (in den 1990ern) Grablichter vor dem Grabstein abgelegt haben – vielleicht haben Sie ja in der Zwischenzeit etwas darüber gehört?

In jedem Fall ist die Geschichte von Ukrainer*innen in Deutschland äußert spannend, wie ich während meiner Recherche erfahren habe. Ich komme in nächster Zeit gerne einmal darauf zurück Sie zu kontaktieren!

Ich danke Ihnen erneut für Ihre Unterstützung bezüglich der Grabsteinumstellung! Es freut mich wirklich sehr, dass immer mehr Menschen erkennen, dass der Stein dringend einen würdigen Platz erhalten muss. Das Anliegen den Stein umzustellen und mit einer Gedenktafel zu versehen, habe ich bereits Mitte/Ende Januar dem zuständigen Friedhofausschuss übermittelt, bislang ist aber (vermutlich auch durch Corona) recht wenig passiert.

Wenn Sie ganz praktisch helfen möchten: Sollten Mitglieder des Ausschusses kennen (eine Übersicht ist hier: http://friedhof-wolfhagen.de/verwaltg/aussch.php), sprechen Sie diese gerne einmal an oder fragen Sie bei Herrn Prus/der katholischen Gemeindeverwaltung in Wolfhagen nach, ob diese nicht auch eine entsprechende Anfrage an den Aussc´huss stellen möchten. Je mehr Menschen in Wolfhagen Interesse an dem Fall zeigen, desto eher kann ich mir vorstellen, dass sich da bald etwas bewegt.

Herzliche Grüße

Phillip Landgrebe

irina Chetinin

Dear sir Landgrebe,

Vielen Dank für Ihren tollen Artikel. Es wundert mich, wie großartig Sie in so kurzer Zeit gearbeitet haben. Seit vielen Jahren suche und sammle ich Informationen über meine Familie, die von 1943 bis 1945 Ostarbeiter in Deutschland war. Meine Familie wurde aus der Ostukraine nach Deutschland gebracht. Ich habe viele Dokumente aus Bad Arolsen Archiven bekommen, aber leider ist das alles, was sie haben. Abwesend für das ganze Jahr 1943-1944. Ich werde weiter suchen. Du hast mich mit deinem Beispiel inspiriert! Entschuldigung für die schlechte deutsche Übersetzung. Ich lebe in der USA.

Sincerely,Irina

Phillip

Dear Ms. Chetinin,

thank you very much for your kind feedback and I am delighted that you have been inspired by my research! It’s really great that you are researching your family’s history because unfortunately way too many stories are already forgotten.

I wish you every success with your research! If I can support you with my knowledge of archives in the North Hesse region, please contact me.

Kind regards,

Phillip Landgrebe

Volker Gaul

Sehr geehrter Herr Landgrebe!

Vielen Dank für die spannende Darstellung Ihrer Forschungsergebnisse. Wir planen als Klasse eine kleine Ausstellung zum Thema Zwangsarbeiter in Dithmarschen (S-H). Wäre es möglich, dass wir uns bei Fragen an Sie wenden könnten?

Ihnen alles Gute!

Volker Gaul

Dietfrid Krause-viklmar

eine exzellente Stdudie, meinen Glückwunsch! – “Public History” an der Uni Kassel? bei Frau Kollegin Veit? Beste Grüße, D. Krause-Vilmar