Its legacy crucially carved Europe’s history and shapes its landscape – literally and politically – till the present day: Germany’s past as a fascist dictatorship, committing human crimes and plunging the world into another war plays a central role in German national identity and its culture of remembrance. But what if this burden of the past enters your private space? How does it feel to find out about your own family’s involvement in the heavy-weighing Nazi past? Our author Kelly knows.

My Ancestor’s Faces

The Green Cigar Box (photo: private)

Whenever I open my great-grandfather’s green cigar box, my imagination tricks me into thinking that I can smell the faintest hint of tobacco. In reality, though, the tin case has not contained cigars in decades. Betraying its original function, it has become a little box of memories. Memories of a time long before I was even conceived of.

I have looked through the collection of photos inside so often that the strange faces have become familiar. Nonetheless, they are faces I know only in black and white. When meeting the forever-encapsulated eyes of my ancestors, I am overcome by a sense of familiarity that goes beyond the sheer number of times I have gone through each one of the portraits and snapshots. I tell myself that I can recognise my aunt’s eyebrows, my uncle’s eyes and my great uncle’s chin in the man I would have addressed as great-grandpa had he lived long enough to meet me. All I can do now is look into the eyes of a man dressed in a Wehrmacht uniform, handsome and strong-chinned, and ask myself what was going on in his head. I will never know.

Big-Bellied and Cigar-Smoking

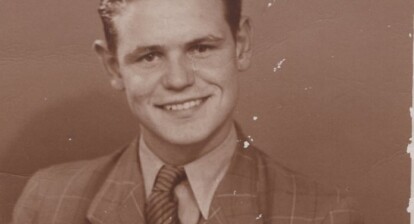

1926 (photo: private)

The stories I have heard about my great-grandfather are plentiful. My mum fondly recalls her big-bellied, cigar-smoking Opa, who taught her how to ride as a little girl. A cavalry soldier whom me and my sister credit with our passion for horses and whose near legendary stories driving an eight-horse carriage in military competitions, winning both medals and my great-grandma’s heart have become a part of the family mythology. I am told my great-grandmother – a true Hanseatic North German – always wanted to marry a man in marine uniform, but when this desire remained unfulfilled, she settled for a cavalry uniform and the man dressed in it.

When looking at the swastika on his uniform from 1933 onwards, I cannot help but ask myself the typical post-war generations’ question: Was my great-grandfather a Nazi?

Quadrille in Oldenburg 1927 (photo: private)

Was my Uropa a Nazi?

For a long time, my family hid itself behind the common yet factually incorrect fable that he was a soldier in the Wehrmacht, not one of those “awful SS-Nazi criminals”. As Germany slowly grows to accept that the Wehrmacht was more than just a little involved in war atrocities as well as the execution of the “Endlösung” (“final solution”) on a national level, my family still refuses to jump on this train of acceptance. And to be honest, I would argue that most families still try to uphold the narrative that Opa war kein Nazi (“Grandpa wasn’t a Nazi”). More than that, my family has perfected the German art of totschweigen (hushing up) what truly happened. All I know is what I have been told by other relatives, for I, too, follow the family tradition. Questions are met with shrugs, assertions that “they don’t remember” and the obligatory repetition of the much heard “and anyway, no one spoke of it back then.” Of course, I could dig into the depths of the internet, I might be able to find out what regiment my great grandpa led; I might find out what prison camp he managed and where exactly he fought at the Ostfront (“Eastern Front”), what atrocities he might have been involved in. But I never wanted to.

The Germans’ Struggle With Their History

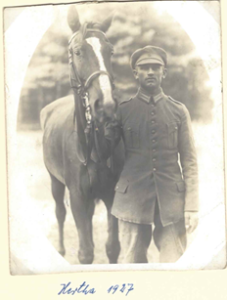

My great-grandfather with his horse Hertha in 1927 (photo: private).

Having gone through German higher education, images of dead skeleton-like bodies piled on top of each other in the worst, most industrialized genocide humanity has ever seen were part of my curriculum. Documentary footage of the liberation of Auschwitz, the visit to an actual concentration camp many pupils went through, and supplementary photographic input of Eastern Front horrors all are part of the German endeavour to shock students into painful awareness of their country’s irksome past. Rightfully so, at least regarding the topic at hand. More than any country I have ever lived in (Germany, Australia, UK, New Zealand, Canada), Germany is conscious of its past, the weight of reconciliation, responsibility and commitment to peace weighs heavy on those of us lucky enough to have been educated here. It is this awareness that – one hesitates to use the expression for all the baggage it carries – makes me proud to be German.

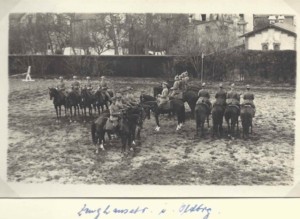

At the Eastern Front in 1944 (photo: private)

Facing the Truth

I am well aware that on paper, my great grandpa’s record does not exactly speak in his favour: Born into the generation too young to fight in the First World War, he would have likely grown up hearing of the glorious, stable Kaiserzeit (“German Empire”), of the wide-spread conspiracy about the “malicious” Jewish-Socialist betrayal that caused German defeat and had landed the country in the chaos of democracy. The earliest photos of him in uniform I have are from the mid-1920s, either posing in an earnest portrait or next to his favourite horse, Hertha – a chestnut Trakehner mare. Among the first wave of officers to fight in Hitler’s war against the world, he somehow managed to survive until 1945. So yeah, frankly speaking, statistically, he was probably a Nazi. And if not, he sure as hell did not express his disagreement with the political situation to a degree that would have cost him his high rank in the military.

A Life That Commands Respect

Over the years of trying to accept this statistical likelihood, I have come to the conclusion that none of it matters. That I have not the faintest right to judge him as a white, middle-class, educated young woman who grew up during the most peaceful times Germany has ever seen.

Return From Imprisonment in December 1955 (photo: private)

Why? Because when my great-grandpa spent his last furlough with his family to see his son for the first time in March of 1945 and his relatives tried to convince him to go into hiding and wait out the inevitable defeat, he said no, he had to return to his comrades. Because when his train arrived at the Eastern Front, he fell straight into the hands of the Soviet Army. Because he was imprisoned in Siberia for the next ten years. Because when he finally returned to his family after sixteen years of war and its aftermath, he was a near stranger to his nineteen-year-old daughter and eleven-year-old son. Because he woke up screaming from nightmares for the rest of his life, though he never broke the silence on what he had actually seen and experienced. A prime example of Germany’s war generation, he lived out the rest of his life in the sleepy province of Schleswig-Holstein, until his tired heart stopped beating twenty years after the reunion with his family.

A Shared Legacy

Most Germans who have ancestors that lived in Nazi Germany are in the same situation as me. Only a minuscule minority can “pride” themselves in being the descendants of resistance fighters, however I would argue that it is time to move on from our individual heritage. What matters is that from 1933 (and before) to 1945, 60 million Germans went along with a totalitarian fascist dictatorship, fought in its war, which ultimately led to the death of 75 million people. Doubtlessly, had half of the population gone to the barricades in protest against Hitler and his regime, the war would not have taken place the way it did. But they didn’t. And thus, generations of Germans have struggled to come to terms with the personal legacy the Nazi regime left for them.

Moving On?

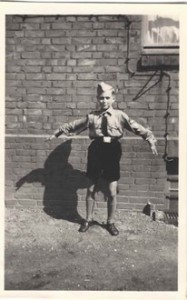

My Great-Uncle in Hitler Youth Uniform (Photo: private)

My German side of the family (the other side hailing from Australia) was very much the perfect example for a post-“Stunde Null” – the metaphorical “hour” from which everything began anew from the wreckage of the world war – a capitalist success story. Out of the ashes of Hamburg’s ruins, my Opa, who had fled from Eastern Prussia when he was seven, built up his business, ultimately making him the family patriarch. To this day, whenever we have family reunions, he will make a very official speech and toast to our family and to European peace. Yes, European peace. I distinctly remember the urge in my younger self to roll my eyes every time Opa reached this point during his obligatory speech because this was when he would start tearing up. My wine-bellied, authoritative German grandfather would tear up in front of the entire family. Every. Single. Time. He would usually start by saying something like “well, back then [i.e. after the war] we had nothing” and end asserting how thankful and proud he was that after the disaster of World War Two, nearly eighty years of peace have made Europe flourish.

Of Closing and Carrying the Box

This is the legacy we should carry on. Cheesy as it may sound, I believe that learning from the horrific errors of our predecessors and contributing to European unity and peace is what is left for us to do. I can’t change what happened in the past – yes, our great-grandparents probably committed terrible acts during the war, but I believe it is time for me to close the green cigar box of memories and detach myself from the personalisation of a war that I only know from books and movies. I will always carry it with me, however, this little tin box. It is a part of my history, my family and myself. And who knows, maybe it will even help me leave behind a better world than the one I was born into.