Passed from generation to generation, European folk tales have taken down the barriers of time. But many tales which generations all over Europe grew up with are more than sweet stories told to children – they hide darker roots. Neasa from Ireland and Rusudan from Georgia discuss how folk tales from different countries shaped their personalities and share insights into not so “happily ever after” origins.

Inhibited with fairies, witches, giants, enchanted objects, and other magical creatures, European folk tales are as old as time. Written down after millenniums of verbal adventures, they are reflections of unity between different generations and nationalities. Tales of Rapunzel, The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast and many others are dear to almost everyone’s hearts, no matter which sub-category of European folk tales they come from – Celtic, Germanic, Romanic or Slavic. Because of the centuries spent evolving side by side, they show lots of similarities regarding themes and creatures. Even Georgian folk tales, which are largely inspired by Asian traditions, have parallels with those mentioned above. Let’s take a closer look..!

Affection for Tragedy?

Neasa: A lot of young people would say that Disney films were part of their childhood. They are embedded into my memory as well. Another thing that defined my childhood and inspires me until today, is folklore, specifically Irish tales. I grew up with medieval tragedies such as “Deirdre of the Sorrows” and “The Children of Lir”, and I even own a picture book called “Irish Legends for Children”. Its beautiful illustrations fuelled my interest in Celtic mythology, which is ironic. As someone who loves happy endings and detests stories ending with death and despair, I always found kinship with the tragic tales from medieval Ireland.

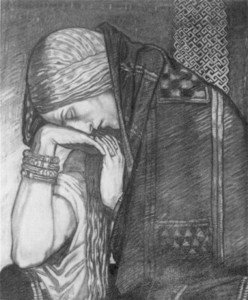

‘Deirdre of the Sorrows’ by John Duncan, PD-Art, over 70 years old (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

In “Deirdre of the Sorrows”, the heroine Deirdre was the most beautiful woman in Ireland, destined to bring bloodshed to the men of Ireland and Scotland. She is my favourite character in Irish folklore because of her passion to live life the way she wants. I admire her strength and determination to escape an arranged marriage with a king by fleeing with the warrior Naoise. She persisted, despite all the hardships. Cinderella has always been one of my favourite tales because of the uplifting story about a poor servant girl who marries a prince and lives happily ever after.

The Truth Behind Cinderella’s Popularity

Since Cinderella motifs have appeared in different parts of Europe and across the world, I wondered why this tale has been repeated more than 500 times by different cultures under new titles for hundreds of years. I think it is the fight for freedom and the rags to riches aspects that captivated readers all over the world. A story about a mistreated girl becoming a princess with the help of a lost item reflects the sense of justice of people who told the tale.

Eyeless Villains and Swiss Heroes

Another parallel between tales across countries: Giant creatures lack one eye. For example, Fomoire giants from Irish mythology and Cyclops from Greek mythology. This motif is intriguing as it builds a picture of what our ancestors believed representations of evil were. Some storytellers associated physical mutations with something frightening and lawless. I find such literal understanding unfair. It made me feel sympathetic towards the monstrous creatures because I believe kindness comes from within. For example, in some Georgian tales like “Natsarqeqia”, giant devils are just gullible creatures with no evil intentions. While witches were believed to have mysterious powers, it was the fear of the unknown that fuelled people’s negative emotions.

The motif of justice, as well as freedom, is prevalent in some European tales. My friend Julia from Switzerland told me about William Tell, a Swiss folk hero who may or may not have been based on a real person. He was courageous enough to rise up against the Habsburgs. “Tell killed one of the Habsburg leaders, which spurred the Swiss on to stand up to the Habsburgs. Therefore, his character became a symbol of freedom and autonomy for the nation, especially in times of war”, says Julia.

Never Eat a Golden Egg

Some stories are much simpler than others, but still incorporate recognisable themes. My friend Nadzeya from Belarus told me about a Russian fairy tale she grew up with called “Ryaba the Chicken” (“курочка-ряба”), which tells the story of a poor elderly couple and a chicken. One day, their chicken laid a golden egg. The grandparents tried to crack it in order to eat it but were unable to. Eventually, a mouse ran up to the egg, waved its tail, and broke it, causing the grandparents to weep in despair. Then the chicken said “Don’t cry. I’ll lay you a new egg. Not a golden one, but a simple one.”

As a child, Nadzeya didn’t understand the moral behind it, but “rereading it now, I think it means that if a man is not clever enough to recognise a wonderful opportunity, then no one can help him. Fate had given the grandparents a chance to become rich, just by selling the egg. But the grandparents didn’t think about what else they could do with it, apart from eating it.”

Swans: More Than Birds

The Children of Lir sculpture in Dublin’s Garden of Remembrance (Photo: Private)

Another reason for my affection for folktales is the animals, especially swans. They have significance in the European storytellers’ minds. I consider swans to be symbols of innocence and purity. For example, in an Irish tale “The Children of Lir” children are cursed to live as swans. These birds also taught me the tragic beauty of sacrifice and doomed love particularly in the case of Aenghus, the Irish god of love. He falls in love with a woman who transforms into a swan, and changes into one himself to be with her. According to the Finnish epic “Kalevala”, an attempt to kill a swan was punishable by death. Seeing the swan as more than a pretty bird, but as a pure, symbolic creature instead, is what European tales have in common.

A Georgian View: One Tale a Day

Collection of fairy tales in Georgian (Photo: Private).

Rusudan: As a Georgian, I grew up with not only Caucasian, but with European and Asian folk tales, too. For two years, my father used to bring me a new fairy tale every day. The excitement of reading folk tales from other countries made me dive into these far-away fantasy worlds day by day. When I was growing older, I gave most of them away, but the ones I loved the most stayed in my collection until today.

They are all unique in their own way, but the similarities are there. The villain that used to scare me the most in Georgian folk tales was Devi – a giant, hairy creature with many heads or horns. I agree with Neasa that monstrous creatures were seen as representations of evil. This must be the reason why I felt insecure while reading about them.

How I Became a Witch

Looking at it from an adult’s perspective, I too realised that the physical imperfection should never be paralleled to one’s character. It was then that I saw witches in a new light. I learned that in the tropes of fairies with kind intentions, and of old evil women living in secluded areas, they were not only seen as mythological creatures. Some people considered them to be real. In medieval times, lots of women were actually accused of witchcraft and were executed. The most infamous event perhaps is the Salem Witch Trials.

Learning about these historical events, I realised that the evilness of the witches depicted in fairy tales was the result of people’s hatred for those being different. My sympathy for them grew. I started to think that the witchy power our ancestors told stories about was the trait of being a strong, independent woman, smart and always ready to resist if necessary. It was these abilities that were seen as something dangerous in former times. My personal consequence: I joined the generation of the “granddaughters of the witches you could not burn”.

Triggering Chinkas

Being the exact opposite of giants, little chinkas were the characters from Georgian mythology that triggered “two in one” emotions in me. I loved and hated them at the same time. They were tricksters, but also very amusing while executing their pranks. In fact, children are often called chinkas. I never wanted to be the chinka. I rather related to characters like Loki in Norse mythology with the cleverness and ability to see the fifth corner in the Georgian tale called “khutkunchula” (literally translated as “five corners”). It always amazed me how fairy tales could take the literal meaning of something and change it into an allegory.

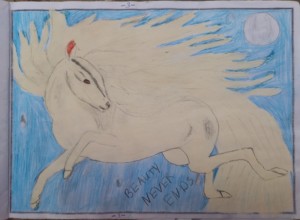

Illustrations were another reason why I loved fairy tales so much. My favorite creature to visualize was Rashi, a magical horse in Georgian mythology.

The drawing of Rashi I did at the age of 12. The choice of the caption, “Beauty Never Ends”, shows the way I used to see beauty in mythical creatures (Photo: Private).

Under the Sea: Bittersweet Memories

Neasa: As a half German, I also gained a fondness for fairy tales recorded by the Brothers Grimm, though my earlier understanding of these tales was defined by Walt Disney. “The Little Mermaid” was my favourite film because of its catchy songs, the memorable characters and an underwater city inhabited by mermaids. I especially adored Ariel, so it was mind-blowing when many years later I read the original “Little Mermaid” tale by Hans Christian Andersen.

It was upsetting for me to learn that this story had a much darker ending than the film: The prince ends up marrying someone else, the mermaid chooses to end her life and becomes a spirit of the air.

A Mirror of Reality

I was also surprised to find out that Andersen implemented a Christian message in this tale. When the Little Mermaid becomes a spirit of the air, she is given a few centuries to earn her soul by doing good deeds for mankind so that she can reach heaven. This is very similar to how Irish mythology was recorded in order to suit the medieval Christian society context that it was being written in, while successfully preserving the original traditional tales.

When stories are written, they are adapted to suit the society of the time. The moral of Andersen’s story is to teach others that if soulless mermaids can find a way to get to heaven, so can all humans. In the end, it is a story of redemption because of the mermaid’s selfless act of mercy towards the prince. “The Little Mermaid” mirrors the former moral norms and hence gives us more than just a simple, happy ending.

My Eye-Opening Moment

Rusudan: I clearly remember the moment when I realised I had a passion for folklore. It was seven years ago, when my teacher called the children Kikimora (an evil spirit in Slavic mythology) because of the squeaking noises they were making. Being the only one in the classroom who understood the parallel and bursting out laughing, I realised how much time I was actually spending reading tales and studying mythology.

From then on, I dug deeper to find out how original versions of famous Disney adaptations really ended. The most memorable one for me was Cinderella, in which in order for the shoe to fit, the stepmother makes the stepsisters cut off their heels and toes. Some versions deal with the theme of revenge – as the bird gouges out the stepsisters’ eyes.

Dark for a Reason: Light Bulbs of Life

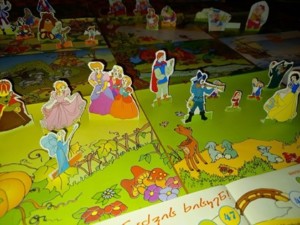

Reading such dark origins made me reanalyse the folk tales I used to read the most. “The Little Mermaid” shook my conscience just like it did to Neasa. The happy endings I always used in my paper theatre while playing with my friends and family, hid much darker roots than I ever expected.

The paper figures and sets of different tales I used to put on shows with my friends and family (Photo: Private).

After years, I concluded that the reason European folk tales have dark roots is simple – to provide generations to come with lessons about reality and the hardships of life: Dedication is not always enough, luck plays a role as well. Loving someone does not mean they will love you back. Sometimes it takes sacrifice to make dreams come true. Reading folk tales is another way of dealing with history, revealing the dreams, fears, values and structures of societies centuries ago. This is the reason why the books my dad bought me when I was little still have a place on my shelf – and will be handed down to my own children one day.