The European Union heads for the ballots in May. What current and future challenges is the European Parliament facing? And how did the elected body develop in the first place? Our editor Gregor talked to the committed European Mechthild Roos, who is doing research on exactly these questions.

EU citizens who are 18 (in Austria and Malta 16) years old or older will be asked to cast their votes in late May 2019 . With this 9th election for the European Parliament (EP), we celebrate 40 years of elections for the EP: The first direct elections took place in 1979. For Gregor, a young Eustorian, and millions of other young Europeans, this will be the first time to participate in EP elections.

Gregor talked to a young German historian and political scientist who has looked closely at the EP and its evolution: Mechthild Roos finished her PhD on the history of parliamentary representation at the European level at the University of Luxemburg and is now a lecturer of Comparative Politics at Augsburg University. She shares both personal reflections and – for our expert readers – historical insights from her research.

“I’m Absolutely Going to Vote!”

Q: Mechthild, let’s start with a personal question: Will you be voting in May?

A: Of course, I will be voting in May. How dare you ask that question! If I didn’t vote, I would consider this a statement against the institution, against its legitimacy, against the necessity to have a democratically elected body at the European level. Therefore, I’m absolutely going to vote!

This election, and EP elections more generally, matter to me to some extent for very personal reasons and to some extent for academic reasons. Scientifically because I have studied the EP for more than five years now, so of course its further development is very close and interesting to me.

Voting and Euroscepticism

Q: On an even more personal level – in a time where Euroscepticism becomes normalised, where does your pro-European attitude come from?

Personally, my pro-Europeanness comes from a background of being an Eastern German Catholic. My European experience has been shaped a lot by my parents, who had to live under a regime with strictly closed borders, a regime that practically did not allow them to live their faith without repression and denied them full political and human rights. For them there was no such thing as an open Europe, and they have passed this down to me and my siblings. My appreciation of Europe comes to a significant extent from how my parents talked about it.

Deepening my Personal Sense of “Europeanness”

Q: What did your parents tell you about Europe? How did this impact your life?

They taught us to recognize and acknowledge the importance of open borders, of peace on EU territory, of freedom of movement and guaranteed political and human rights. The fact that Germany is a member of the EU allowed me to study in Luxembourg, conduct research in the UK, Italy and the Benelux, to participate in numerous conferences and research projects all over Europe without noteworthy complications.

Without Europe’s open borders, I would probably never have got to know my partner, a Swede, with whom I experience this open Europe at home, everyday: in our multilingual communication, in discussions about politics from different national and transnational points of view, merging cultural traditions, ranging from different holidays (Midsommar is great fun!) to the usage of cutlery on the dinner table (a personal knife for everyone – the German way – vs. one knife per food item, shared by all – the Swedish way) … Indeed, all such experiences, ‘professional’ and private, allowed me to deepen my personal sense of “Europeanness”, which I consider a much stronger identity for me personally than my “Germanness”.

A Sense of Europe Growing Closer

Q: Let me circle back to my first question regarding elections – can the institutional bodies of the EU contribute to a sense of Europe growing closer?

For me, having a democratically elected parliament at the European level is a necessary element of creating European unity, including an institutional system that is able to regulate, and to guarantee democratic legitimacy, of European integration, securing the democratic future of Europe.

Q: Young people are the ones getting to know Europe personally much easier than their parents’ generations. Be it by travelling, student exchanges and transnational youth projects or the Union’s Erasmus+ programme. Why are these young people still less likely to vote than the average European?

A: This is sad… I think it would be interesting to compare the turnout of the EP elections with the turnout of national elections, to see whether we can observe similar patterns among different age groups.

In many European countries, especially in those with high unemployment, e.g. in Southern Europe, young people might feel that the EU has done very little for them. Indeed, they might have the impression that the EU has pushed their countries into crisis and economic difficulties – which I do not think is generally the case, but it might still be a perceived reality. Furthermore, this may of course be related to voter fatigue, to the young being tired of the big moral club: “You have to appreciate the EU as a great thing! You have to be grateful for the opportunities it gives you!”

Does EU Really Have an Impact on our Lives?

Erasmus+ enables to discover the EU. (Photo: Laurie DIEFFEMBACQ / European Union 2017 – Source : EP / EP-062639A)

Q: Is the EU in this way too far away from the day-to-day life of the young?

Yes, the EU is considered something that happens very far away from them, that is not having any impact on their daily lives. This coincides to some extent with a lack of reflection what exactly the EU and Europe mean in their everyday lives. It is exactly what you mentioned before regarding travelling, or even simple processes like ordering your products online from another EU-country, and not having to go to a customs office to get your parcel.

These things are not really perceived as coming from the EU, not least because young people do not know how things were before the EU’s existence. What the EU is and does, and especially what the European Parliament is and stands for, is perceived as something detached from everyday life, happening at completely different levels. All that might contribute to the lower turnout.

Asking the Expert: “The Decision to Create a Parliamentary Assembly at all was Decisive”

Q: The EU is divided into several institutions with very different tasks. Many Europeans still perceive the EP as a ‘lame duck’ compared to the Commission and the Council. But historically, the parliament has gained incredible influence. What would you consider as the most important steps in this process?

A: This step-by-step approach is tricky when it comes to the European Parliament, because in my opinion the main and major step in the history of the European Parliament was the decision to create an assembly in 1951 in the first place during the negotiations of the Treaty of the first European Community. The decision by the founding member states’ governments to create an assembly which was not composed of ministers or bureaucrats, but of parliamentarians – this is what I consider the event which determined most significantly the following evolution of the EP into the parliament it is today.

This early assembly, formed in 1952, consisted mostly of pro-European parliamentarians, of delegates from the national parliaments who in their vast majority were in favour of European federalism, of an ever-closer Union, and of having a powerful, fully-fledged European Parliament. This was the crucial step: These parliamentarians, despite an extremely narrow formal basis (in its early years, the EP had very few powers: it could control the Commission and decide on its own rules of procedure, but had no legislative or budgetary powers), were strongly engaged in shaping the Community’s parliament.

Has MEP’s Mindset changed?

They commented on community legislation from the very beginning, even if they were not asked; they claimed to have a right to change legislation; they tried to control the Council; they tried to control the budget much earlier and to a much larger extent than the Budget Treaties of 1970 and 1975 allowed. Importantly, they did not behave like national parliamentarians, which they all were at that time first and foremost – but like Europarliamentarians. To some extent, the MEPs’ mindset has not changed much: The EP has remained eager to enhance its position, to gain more powers, and eventually to reach a parliamentary role that can be compared to national parliaments, a role it has to some extent reached today – not least, of course, with the help of Commissioners and ministers sharing the MEPs’ pro-European ideas, and considering the EU in need of democratic legitimacy through a powerful parliament.

Research Experiences: Surprises and EU institutions being BFFs?

Q: What surprised you the most when conducting your research on the EP’s history

A: Difficult … Probably the extent of influence the MEPs had without formally having the necessary power. I was amazed how often EP amendments and initiatives made it into EU legislation, word by word, from the 1950s – even though the EP only gained noteworthy legislative power through the Treaties of the 1980s and 1990s.

Until then, the Commission and the EP were kind of “BFFs“, whereas the Council was perceived as an opposition by the Parliament. Knowing this, it surprised me that the Council agreed repeatedly to restrict its own power by empowering the EP, and that the member states’ governments limited their possibilities to act intergovernmentally, often behind closed doors. For instance, already in the 1950s the Council agreed to appear in front of the EP, and hence in public, to justify its actions in front of a body that was legally speaking still far from being a parliament!

The Council contributed significantly to the empowerment of its biggest counter-actor by treating the EP to some extent as if it was a proper parliament. Of course, there are rationalist reasons for that. Council members sought to legitimize European policies, to convince European citizens that their interests were represented in the European Community. Still: the extent to which that empowerment happened really surprised me.

Personal Hopes for the Future

Q: What are your personal hopes for the elections in May and the EU’s near future?

A: My biggest hope is that the EU continues to exist. Unfortunately, in today’s turbulent times that needs to be said. If you had asked me two or three years ago, I would have said: that’s obvious – but given the current developments in the EU, I do not consider it quite so obvious anymore, although I am convinced that some form of European integration will prevail.

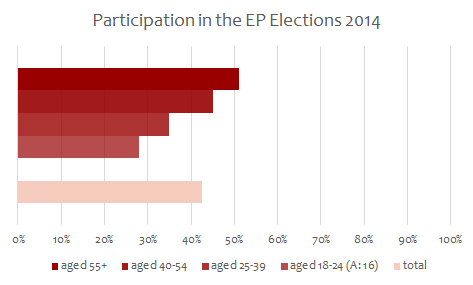

My personal hope for the election itself is that we have a turnout higher than 50%, if possible, in all member states. I know that this is utopian; I know there will be some very “good” member states, for example Belgium and Luxembourg, with their system of compulsory voting. But we also had countries like Slovakia, Bulgaria and Romania with a very sad turnout in 2014. Maybe Brexit has brought Europe closer together, maybe it has made the impact of the EU on their lives more palpable; maybe it has given some people the feeling: “I can change something by voting, and it does matter whether I vote or not!”

The empty hemicycle of the European Parliament in Strasbourg – who is going to sit down in these rows after the elections? (Photo: Mathieu CUGNOT / European Union 2018 – Source : EP / EP-072673A)

Hopes and More Hopes

Q: And what are you hoping for concerning the political results?

This is the other big question: For whom will people vote and who will the EP be composed of after these elections. My hope is that the vast majority of the MEPs is somewhere in the political centre, and that populist parties do not get too much power through too many votes.

I furthermore hope that whoever leads the next Commission is a very present figure. Someone who is recognised, who can share with the people what the EU can do, what benefits it brings to every citizen, both in a rational and a normative, even emotional manner. I truly hope he or she is able to convince people of the added value of European integration.

Q: Thank you for taking the time to answer our questions!

Extra: From a Parliament without Socialists and the British Towards Diverse Representation

Q: Is there a lack of a European identity and European public sphere? Do you observe the development of such an identity in the micro-climate of an institution like the EP?

Towards a more diverse EP: European election campaign in Denmark 1984. (Photo: European Union 1984 – EP / 1984ElecDK)

A: As far as I see, it was rather the opposite. MEPs shared a pretty strong common European identity in the 1950s to 1970s, prior to the EP’s first direct elections, and notably prior to the first enlargement of the European Community in 1973, when Denmark, Ireland and the UK entered. Up to the 1970s, there was this group of fairly homogenous pro-European MEPs, not least because those who thought differently were to some extent kept out:

For example, communists and socialists were not allowed to join the national delegations sent to the EP prior to the late 1960s / early 1970s. Even though in France and in Italy, Socialists and Communists reached election results of up to 30% and were partly even participating in governments, they were kept out of the EP because of their Euro-critical attitude. This of course “conveniently” reduced controversy in the EP a lot.

A Common European Identity

But the more enlargements there were, the more national parties that came in, the more different ideas of Europe were represented concerning what the nation state’s role is, what the Community (and later the EU) should become etc., in other words: the more the EP grew, the less homogenous it became. Now it is as heterogenous as never before.

One might even ask whether there should be one European identity within the EP: It made things easier for the MEPs in the beginning with regard to finding majorities, and it helped the EP to act as one unitary actor vis-à-vis the other community institutions and the member states. But: the EP would not be a parliament if there was no controversy! Indeed, there is no democracy if there is no controversy.