Bloody Sunday, which occurred in Dublin in 1920, was one of the most violent events in the Irish War of Independence, leaving more than 30 people dead. To this day, this period of Irish history still sparks furious national as well as private debates in Ireland. Neasa from Ireland describes how researching these events made her discover that the picture of the perpetrator is less black and white than she expected.

Bloody Sunday: A Turning Point in Irish History

The 21st November 1920 is remembered for being one of the most violent events in the Irish War of Independence, leaving more than 30 people dead. On that fateful morning, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) carried out an operation, organised by Michael Collins, to assassinate British intelligence agents known as the ‘Cairo Gang’. Fourteen agents were shot and killed all across Dublin on that Sunday morning, some in their own homes and in front of their families. As news of the killings spread, there were heavy fears that a reprisal could take place.

Then later that day, a Gaelic football match was taking place between Tipperary and Dublin in Croke Park. Around 5,000 spectators attended the match. Due to suspicion that there were IRA members in the crowd, a force made up of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and the Black and Tans opened fire on the crowd of spectators, killing 14 people, including children, and wounding between 60 and 70 people. Victims were shot, impaled and crushed as they attempted to flee the scene. One of the football players, Michael Hogan, was fatally wounded. The Hogan Stand in Croke Park was later named in his honour. That day became known as Bloody Sunday, an event that was later portrayed in a scene in the 1996 film ‘Michael Collins’.

Worldwide Attention

The events at Croke Park received worldwide attention, and the British authorities were heavily criticised by the US government. Some newspaper outlets even pointed out similarities between the shootings and the Amritsar massacre in India which had taken place in 1919. However, the IRA killings earlier that day received more attention in Britain than the events at Croke Park. When Joseph Devlin, an Irish Parliamentary Party MP, attempted to bring up the Croke Park massacre in the Westminster parliament, he was shouted down and even physically assaulted.

The Impact of Bloody Sunday on the War of Independence

It’s no secret that the events of Bloody Sunday were a turning point in the War of Independence, as not only was British intelligence severely crippled by the IRA killings, but the reprisals later that day also served to boost support for the IRA and led to increased hostility towards British rule in Ireland.

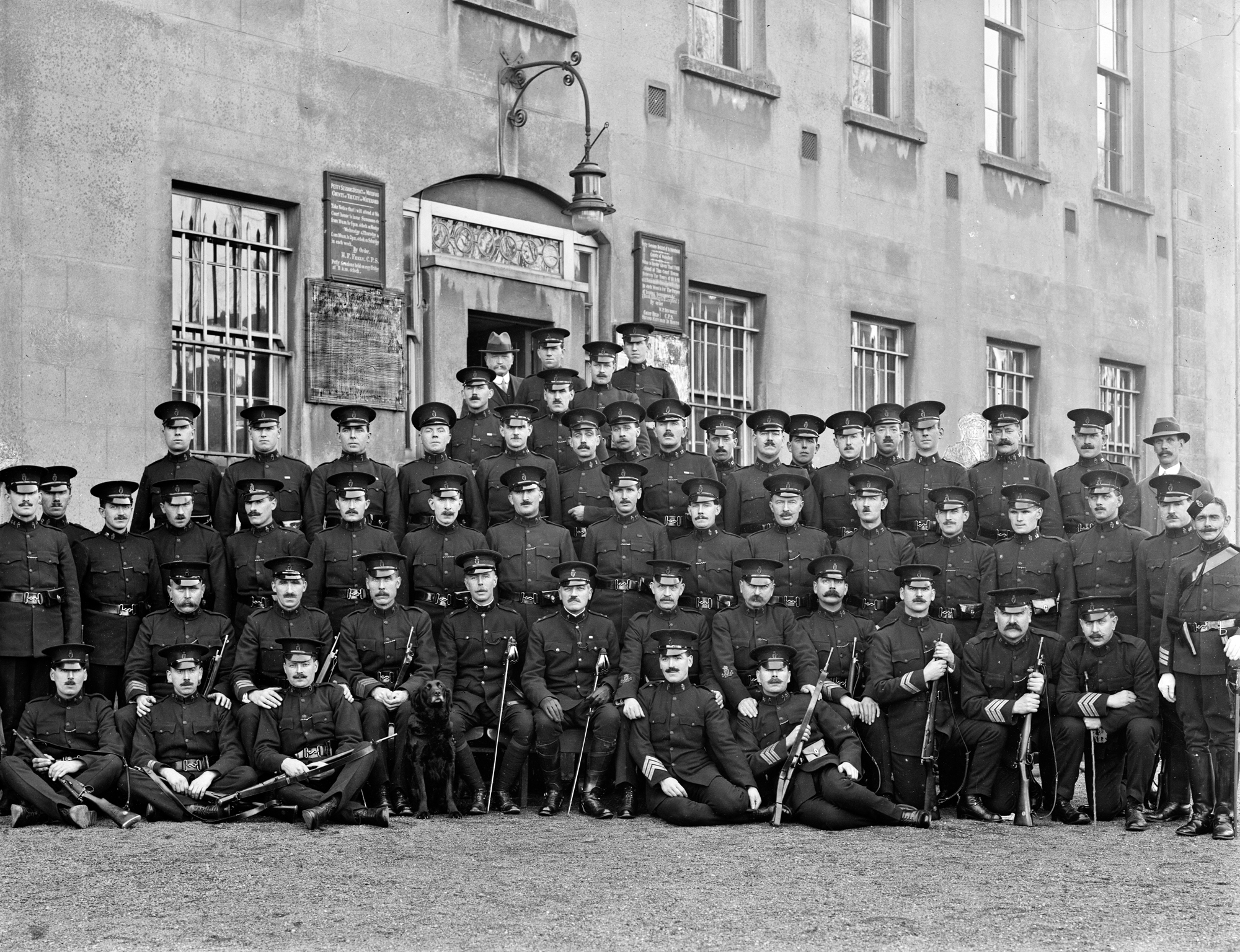

Even now, 100 years later, there are still very strong feelings in Ireland about this dark period of Irish history. Those feelings erupted in early January 2020, when the then-Irish Minister for Justice, Charlie Flanagan, announced to the public that he was planning a commemoration service for members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP), the police forces who served in Ireland between 1836 and 1922. The minister stressed that most of these ordinary men were just doing their job like policemen everywhere and that history had treated them unfairly. This proposal was met with complete uproar by the majority of the Irish public, who maintained that both police forces were acting for the British in opposing the IRA during the War of Independence. Furthermore, to this day, the British constabulary has generally also been associated with the infamous military groups known as the ‘Black and Tans’ and the Auxiliaries, tasked by the British government to assist the British police forces in crushing the IRA.

Controversy and Backlash: Unraveling the Commemoration Debate

Black and Tans and Auxiliaries outside the London and North Western Hotel, in North Wall, Dublin surveying the damage done to their quarters after an I.R.A. attack, https://www.flickr.com/photos/nlireland/6492236861/, CCO

Those opposed to this year’s commemoration maintained that the actions of the police and the Black and Tans during the War of Independence could not be separated as they were all trying to prevent Irish independence. Both the Black and Tans and the RIC have been held responsible for the events at Croke Park in November 1920, and countless other bloody happenings that took place during those turbulent years between 1919 and 1922.

Social Media Storm and Musical Resistance

This proposed commemoration received national attention and was trending on social media, with debates raging between both sides of the argument. The famous rebel song ‘Come Out, Ye Black And Tans’ reached No. 1 in the UK and Irish iTunes charts, as part of widespread criticism of the planned commemoration. Eventually, the event was cancelled, much to the relief of those who were passionately against it.

Like most Irish people, I opposed this commemoration and was rather pleased when public pressure led to its cancellation. However, as this topic was of great interest to me, I decided to do some research. To my surprise, I found that the circumstances surrounding the British forces policing Ireland at the time wasn’t as black and white as I had previously thought.

Family Ties and the Shades of Complicity

In no way will I be attempting to defend the actions of British authorities in Ireland, as none of that can ever truly be justified by anyone. Instead I will discuss who the RIC were, as well as some discoveries I have made about my own ancestors and their involvement with the RIC. I will also deliberate over the question of whether I consider my family members to be among the perpetrators.

My Family History

During this past year, I have become fascinated with my own family history and tracking down my ancestors. Therefore, I was rather shocked to discover over time that at least seven members of my own family, three of whom were my direct ancestors, were themselves members of the RIC.

Conflicting Heritage

When I think of the RIC, I think about that disturbing eviction scene in the film ‘Black 47’, which takes place during the Great Famine. At first, I felt a deep shame that my ancestors may have partaken in such horrific events, but I was also curious. What made them decide to join a force that served the British Crown, while knowing that what they were doing was traitorous in the eyes of many fellow Irish people, who suffered under persecution and poverty brought on by British colonialism?

Unraveling Motivations: Understanding Irish Society

In order to understand their motivations for joining this force, I also had to understand Irish society and the general system that existed in rural Ireland during the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. Ireland was an extremely poor country and had been for centuries while under British rule. One of the only ways for an Irishman to earn a decent living was to serve the Crown in one way or another, either in the army or as a police officer.

A Family Tradition: The Case of Looney

Both seem to apply to my great-great uncle, James “Jim” Looney, who was killed while serving in the British army during World War 1. Until recently, I had always believed that he was an ordinary young countryman who, for some unknown reason, had decided to go to France to fight for Britain. Therefore, I was rather surprised when I accidentally discovered his name on an online list of RIC members who had “answered the call” for army volunteers during World War 1. Intrigued, I decided to dig a little deeper into this uncle of mine, even managing to find online copies of original documents.

Like most RIC men, Jim came from a Catholic farming family. Being a part of this force ran in the family, as his father and grandfather before him were RIC pensioners. He was initially appointed to the RIC on 17th August 1914 but was discharged two days later as the surgeon deemed him unfit for service. He was then reappointed in October 1914, and served as a constable in Counties Clare, Roscommon, Dublin and Cork.

A Unique Story

Jim’s story interests me more than all of my other relatives because his story is more unique than theirs. In November 1915, he was selected for service in the British army for World War I. In fact, he was among the 752 RIC men who were called up by the inspector general at the time to go and fight in France between 1914 and 1918. He served in the Irish Guards regiment for about three years, during which they took part in a major German military offensive known as Operation Michael. They fought in the Battle of St. Quentin, the First Battle of Bapaume and the First Battle of Arras. He was killed in action by unknown causes on the 2nd June 1918, in France & Flanders, just before the Battle of Albert. He is buried in a village called Bienvillers-au-Bois, Arras, near the French-Belgian border. I hope to visit his resting place someday soon.

A memorial for 500 local men who served in World War 1, Ennis, Co. Clare (Photo: Private)

It’s possible that Jim was under a lot of pressure from his RIC colleagues and superiors to join in the war effort. But perhaps there was another reason too. I recently spoke to my great-aunt Mary and great-uncle John, and although they didn’t have any particular insight with regard to their uncle Jim, they did mention that many Irishmen fought in World War I because it was supposed to be the war to end all wars, meaning freedom for all nations. Therefore, a significant number of Irishmen may have made the decision to fight in the British army because they believed that in so doing, they were helping Ireland to finally become a free nation.

If that was the case, then it is very ironic that Jim’s name is included in the book ‘The Royal Irish Constabulary: A short history and genealogical guide…’ by Jim Herlihy, which lists RIC men who were honoured for their contribution towards the British Crown, when in fact his possible motivation was to ultimately free Ireland from the Crown.

Conclusion

During my research, I deliberated a lot about how I feel personally about my RIC relatives, and what I would have done in their place. I have come to the conclusion that I do not consider my ancestors to be among the perpetrators. I realise now that joining the RIC or the British army was likely not an easy choice for any of my relatives, because they probably felt as though they had no choice. I’m not sure what I would have done in their place, but I do know that these men had their own families to think about. They would have sacrificed the respect of many of their relatives, friends and neighbours just so they could secure permanent and pensionable employment.

As I have said before, I am absolutely not trying to justify all the atrocities that the RIC committed against Irish civilians. It cannot be ruled out that my relatives may have partaken in these terrible events while serving in the RIC, because that was part of their job. All I’m saying is that I feel great sympathy for them, because no matter what reasons they had for becoming RIC members or indeed British soldiers, and despite the fact that the latter were on the side that won the Great War, all these men ended up on the wrong side of Irish history. Unlike the Irish revolutionaries of the 1916 Rising and the 1798 rebellion, the Irishmen who joined the RIC and the British Army have tended to be ignored and often despised by subsequent Irish generations because they were working for the Irish enemy, i.e. the British Crown. Because of that, it is very likely that for the most part, they may continue to be airbrushed from Irish history.

Bibliography

Herlihy, J. (1997), The Royal Irish Constabulary : A Short History and Genealogical Guide with a Select List of Medal Awards and Casualties, Reprint, Four Courts Press, 2016

Leeson, D. (2011), The Black and Tans: British Police and Auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence, 1920–1921, Illustrated edition, OUP Oxford

Check out more in out Blog Archive.