What is our first thought when we don’t know something? “Just Google it up!”. Google will celebrate its 20th birthday this year and it is undeniable that the search engine occupies a prominent role in our lives. But could Google (and technology in general) go further and completely replace libraries, archives or even teachers by becoming the sole instrument to research, teach and learn history? Could Google rearrange our knowledge about the past with their untransparent algorithm? Camilla Crovella from Italy reflects on these questions, after attending the Eustory Annual meeting in Turin on these topics.

Happy 20th Birthday, Google!

Researching is a fundamental human activity. Even if some of us would not admit it, nowadays most of us look first on Google to find something we don’t know. The largest search engine in the world is turning 20 this year. It has become our everyday soul mate, memorizing our tastes, reminding us of our timeline and showing us the directions. Smart glasses and watches aside, research is still Google’s bread and butter. And it is definitely still successful. According to a statistics by Interntlivestats, Google now processes over 3.5 billion searches per day and 1.2 trillion searches per year. It will be a satisfying 20th birthday: in 1998, after the launch, the number of searches was around 10 thousand per day (source: Internetlivestats).

Can Google go Even Further?

The question that comes to my mind is: can Google go even further? Could Google become the sole instrument to research, teach and learn history in a better way? Will it completely take the place of books and encyclopedias? And what about the fascinating libraries and paper archives? Is it their unavoidable destiny to become useless?

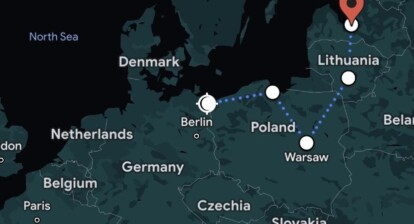

Apparently, I am not the only one asking such questions. Digitalization is one of the main challenges society in general and teachers of history in particular are facing today. A group of teachers, historians and participants from the EUSTORY history competitions, under the patronage of the Körber-Stiftung and the Fondazione per la Scuola, met this spring in Turin to discuss these issues. One key topic was the possibility to use technology as a unique search instrument for historians and students. The Italian history competition decided in 2012 to encourage students to make use of sources available online to experience the possibilities and challenges of digitalization and to foster their digital literacy, i.e. their competences in critical analyzing information on the web (and elsewhere).

Another question was whether history portrayed via movies, TV series and social media can achieve the same learning results as the old traditional book learning.

Some Findings from Turin

Some findings from Turin: first, Valentina Colombi, an archivist with a PhD in modern history who also works as a tutor in the Linguaggi Project at the Fondazione per la Scuola, presented her experiences in researching World War I. She and her students decided to explore digital sources related to the war and started with a Google search. They realized that the majority of websites and even digitized archive collections did not have accurate historical contextualization. For example, they found many pictures of soldiers in trenches. But no additional information, like details about the subject, the date or place the pictures were taken, was trackable via Google.

Challenges in Digital Research: The Role of Libraries and Archives

The same was true for films. Still they found some more reliable websites, but only after a very detailed search via Google. The ordinary search engines (Google, Yahoo etc.), digitized archive collections and the internet in general can be useful as tools to involve students, showing for example soldiers’ life conditions inside a trench during WWI. But Valentina Colombi is convinced that “at least for now in Italy you still need libraries and archives for the real historical documentation and contextualization even digitized collections too often do not provide”. “Thus-she concluded-libraries and archives are not useless in the future because of their longstanding experiences and techniques to secure the reliability of historical sources”.

Edmodo: A Platform for Collaborative Historic Research

Valentina Colombi also introduced Edmodo, a platform where students and teachers from different Italian schools can share documents and ideas and conduct mutual historic research. Edmodo was also an important working tool for two students from Piacenza, who presented the product of their work for the Eustory national competition: digital comics about Kamikaze during WWII. “This innovative way of relating to history definitely made us feel more empathy and eventually keep the stories we researched in mind, like we had experienced them ourselves”, they reported. That would be hard to obtain from book studying.

After reading these lines, some may think I’m supporting the idea that “watching the movie is the same as reading the book (but more relaxing)”. A contradicting example was given in the last presentation about an English TV Series, Peaky Blinders. This show is set in Birmingham during the 1920s (some years after the end of WWI) and focuses on the Peaky Blinders gang and its boss Tommy Shelby. The gang reacts to the poverty deriving from the war via violence, Tommy and other members suffer from psychiatric diseases caused by the fighting in the British army.

Balancing Entertainment and Historical Accuracy

What caught my attention was the theatrical way in which historical events were presented. The reality the show describes seemed close to the historical one, but the language, the characters’ behaviors and personal issues got – in my opinion – too much space compared to the historical setting. The explanation is obvious: it is a show. That is why it is theatrical, why it emphasizes characters’ portray and why it cannot be taken as the only relevant source to learn and teach history. Nevertheless, a series like Peaky Blinders can be a starting point for further exploration of times past.

Technology in Historical Research

This last statement about cinematographic representations of history brought my mind back to the wider category it belongs to: technology. Technology offers several instruments to research, teach and learn history; one of the most common among them is definitely the birthday child Google. Experts’ opinions during the conference and some reflections on my own brought me to believe that those instruments are, at the moment at least, not accurate enough to take the place of traditional sources of information and emphasize the need for critical source analysis.

For sure, technologies like the Google search engine bring many advantages to our lives, first of all giving access to a wide range of information to many people. Accurate teaching and learning of history can benefit from digitalization but not be solely built only on such instruments. So Happy Birthday, Google, let’s go back to the library!