For almost four decades, Francoism defined how to believe and behave as a Spanish citizen. María from Spain remembers her grandmother, who only started dressing freely after Democracy arrived…

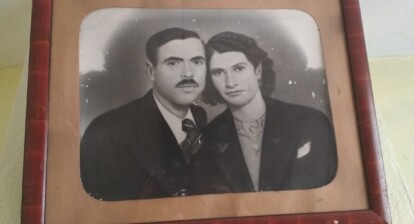

Spain is a country that puts a high value on its traditions. One of them: naming children after their grandparents. I had the luck to be named after my grandmother, María. Sadly, I only got to meet her for a few months, since she passed away when I was a baby. When my family talked to me about my grandma, I always have the photo in mind where she’s wearing a flowered dress.

Dress for a Lifetime

My grandmother wore the same dress for half of her lifetime. It was a dress made from God’s Fabric (clothes worn by processional effigies), whom she vowed to protect her family from disgrace. Only a few months ago I discovered that it was her who made up the concept of God’s Fabric as clothing to be worn daily. Furthermore, although it might sound excessive, the story behind her putting up with her promise for more than 20 years is connected with Spain’s transition to democracy.

Fearing a Tragedy

My grandmother María was my age, 21, when my aunt Carmen was born. She was María’s second daughter, and she would have six siblings, my mother being the youngest one, born in 1964. By that time, my aunt Carmen had gotten sick: when she turned 14, she was diagnosed with neurofibromatosis (a kind of brain tumor). She had to undertake a high-risk surgery.

My aunt was in the operating room for longer than expected. My grandma waited and waited in the hospital, without receiving any updates on her daughter’s state. Fearing her death, she initiated a prayer to God.

A Mandatory Religion

In the 60s, Spain was still under Franco’s authoritarian regime, meaning Catholicism was obligatory. My grandmother had always avoided attending the Mass – she secretly criticized the imposition of religion in the country. But when her daughter Carmen got the severe diagnosis, religion became my grandma’s last resource of hope, as she felt there was nothing left she could do. That’s why she made a desperate vow to God: she would devote to him for life if he protected her daughter.

Luckily, the surgery was successful and my aunt Carmen fully recovered. Out of thankfulness and superstition, my grandmother swore her penance would last forever. Hence, she knitted a violet dress: the only design in her wardrobe thereafter.

Faith, Tradition or Superstition?

It was normal to make those kinds of vows at the time. However, I think that my grandma’s faith was connected to her origins, rather than a genuine religious faith. She never received formal education. She didn’t know how to write. Her only source of information was the church. She lived in rural Andalusia, where the Catholic religion has deep roots in the regional culture. People keep small religious idols in the house for protection and venerate all kinds of processional effigies (wooden sculptures modelled after characters of the Bible).

There’s usually one of those sculptures in every Spanish church. Most are hundreds of years old. It’s a tradition to bring them to the streets in spectacular parades during the Holy Week, where they wear ostentatious clothes. People made promises to god and did penance to make their wishes come true. Men became Penitents (wearing a tunic based on the sculpture’s clothes). The tunic covered their whole body and pointed to the sky. Women were not allowed to wear those clothes, so their penance consisted of walking behind the procession in black mourning dresses.

What is the Holy Week?

Holy Week

The Holy Week is still a tradition heavily present in Spain nowadays. Each region has its particular processions. In Andalusia, the parades are composed of a float representing a scene of the life of Jesus Christ, followed by a float of a mourning Virgin. The costaleros take the heavy sculptures on their shoulders and walk them to the rhythm of a live band, preceded by Penitents, who can now be men and women.

A Particular Promise

My grandmother had prayed to the Saint of our hometown, Nuestro Padre Jesús, who wore a violet tunic with yellow accessories. Therefore, as soon as my aunt Carmen recovered, she bought the fabric that the Penitents wore. Not only did she wish to fulfill her promise, but she wanted to take it a step further. As she thought doing penance only once a year would not be enough, she decided to bear the robe Penitents wore for the rest of her life. She only bought yellow belts and violet Penitent fabric, with which she knitted the identical dresses she always wore.

Nuestro Padre Jesús processional effigie (Photo: Juanma Guardado)

As time went by, my grandmother kept her promise, mostly because of superstition. She was afraid that, if she stopped wearing the clothes made from God’s Fabric, something terrible could happen to her daughter. Her behaviour was rare during Francoist times, but it became even more unique after the dictator died in 1975. Democracy came fast, with a Transition accompanied by the joy of newly-acquired freedom. Spain opened its borders, which meant new ideas and beliefs coming in. However, even when the country’s evolution was mirrored in the flashy, cool clothes people started to wear, my grandmother didn’t want to take off her dress.

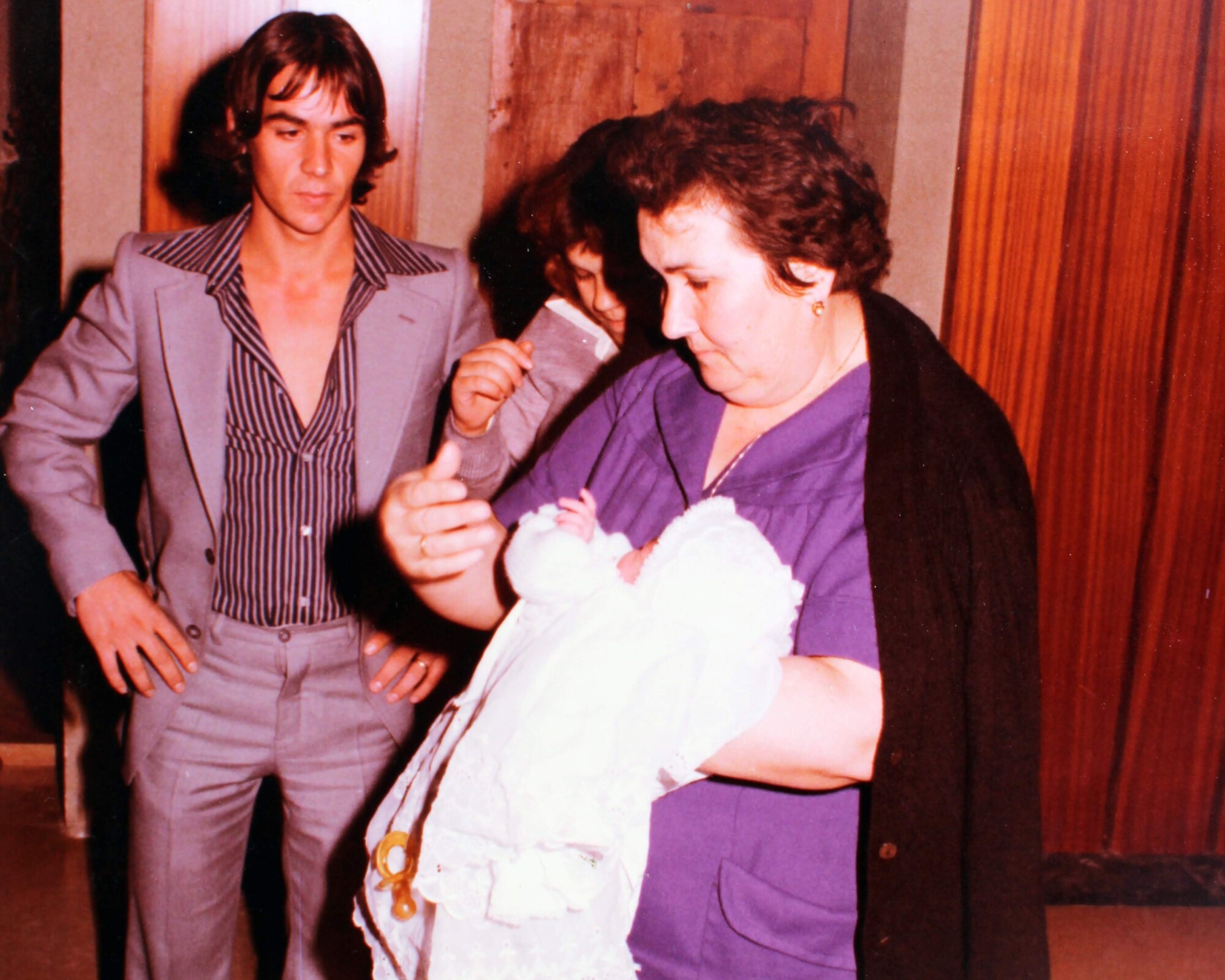

My Cousin's Baptism in 1977

Stuck in the Past

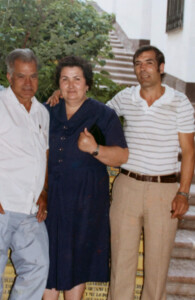

My grandparents with their son, Joaquín (Photo: Private)

María’s children grew up, got married and got children… And she kept on wearing the same dress every single time a photo was taken, which only happened at big family events.

During Francoism the borders were closed and there weren’t many ways to communicate with anyone further than the small suburbs she lived in. However, it wasn’t until the 90s – when democracy was installed and Spain was already part of the European Union – that my grandmother started to question whether something bad would really happen if she stopped wearing the dress.

My grandma went to church to ask the priest. Thereafter, she finally decided to buy new dresses; the priest had assured her that the pope did not consider that as requirements for penance.

Daring to be Herself

Consequently, she stopped wearing God’s Fabric, but only for the last decade of her life. Nevertheless, her new clothing choices were vivid: she loved vibrant colours with cute stamps. I wonder if she had always liked those kinds of clothes.

Either way, I think the story is a perfect reflection of the way Spain changed with democracy.

My grandmother had to live a very tumultuous time. She was six when the Spanish Civil War began. At the time, people never told personal stories, nor shared their opinion. They were afraid that something bad could happen to them or their families, just like my grandmother feared that god would punish her if she took off that dress. When the 40 years of dictatorship ended, darkness was substituted by a saturated light. Most people experienced freedom of will and expression for the first time in their lives.

As for me, I’m just happy that the story had a delightful outcome. Even if it was for a short time, I think my grandmother could finally express herself. Therefore, although there’s only one photo where we’re together, it makes me happy to notice she’s wearing a beautiful, flowered dress.