1474 kilometres or a 30-hour train ride – that’s what it takes to travel from Bern to Bucharest. During a university project, Salome, a young journalist and storyteller from Switzerland, spends two weeks in Romania. She wants to explore the country and meet young Romanians. In diesel trains, hotel complexes, prefabricated buildings, shopping centres and hipster cafés, she discovers the perspectives Romania gives to its youth.

First Impressions in a Good Company

Time flies by quickly when having good company. On my way to Bucharest, I am either asleep on the shaky bed or talking with an elderly woman in my compartment. She grew up in Romania and has been living in the United States for many years. Now, she is on a holiday trip (and what’s most astonishing: to our delight, we meet again at a pedestrian crossing some days later in the busy centre of Bucharest). It is a movie-like introduction, sitting in the gloomy train, hearing stories about her childhood and upbringing in a middle-class family under the communist regime. A bit nostalgic, a bit cliché, maybe.

Nevertheless, what interests me, is today’s Bucharest – a vibrant capital that seems surprisingly familiar to me. Not that I don’t see the typically Soviet buildings, hear the foreign language, or notice the much warmer temperature. But somehow, it feels like any European city.

A Look Beyond The Numbers

However, considering the bare numbers, Romania and Switzerland differ a lot. The statistics for Romania’s youth unemployment rate for example, which has been above 20 % for many years, may not seem promising. For comparison: In January 2023 it was 3 % in Switzerland. In search for peers who are willing to share their thoughts about their relationship with Romania, I meet Ali in the lobby of a conference hotel. The 21-year-old who lives in a village two hours away from Bucharest is attending training for volunteer workers. She is convinced that the high unemployment rate in Romania is also due to the theory-based, outdated education. “It is not designed for the needs of the labor market”, she says. Ali explains that her final exams at high school were almost the same as her mother’s back then and that her student’s books were decades old.

The Power of Grades

Good grades are very important in Romania’s school system. What number you get on your school diploma not only determines whether you will go to university. It also affects which university you go to and whether you must pay tuition fees or even receive a monthly allowance. In Switzerland, good grades are less important when choosing a university. As long as you have graduated successfully from a specific type of high school (which requires good grades to enter), you are allowed to study wherever and whatever you want. And no matter how good your grades in high school were, you will not receive any financial advantages.

Studying in The Capital

Like most students, Teodora lives in one of the state-run dormitories. (Photo: Private)

Due to her good grades, 19-year-old Romanian Teodora has the chance to study at a university in the capital and is delighted to leave her quiet hometown Ploieşti behind. Now, she spends her nights like most Romanian students in a grey prefabricated building. For 50 euros a month, they get a bed in one of the state-run dormitories – with modest amenities: no kitchens or washing machines in the whole building, no microwaves allowed in the rooms, no visitors overnight. Instead, long corridors and wooden doors with stickers from the previous residents are a usual sight. In contrast, Swiss students rarely live in dormitories, which gives them additional freedom and amenities. There are very few dormitories and almost none are run by the state. As Swiss students don’t get financial support for housing, most of them live either in shared flats or with their parents.

School’s Ultimate Goal: a Diploma in Your Hand

“For some, in the end, studying is only about holding a diploma in their hands”, says 27-year-old Andreea about young Romanians. She lives in a Transylvanian town and participates in the same training as Ali, being involved in various NGOs in her hometown. In her view, some young Romanians do not take school seriously enough “even in the big cities such as Bucharest”. Andreea describes their attitudes towards life as an “overall passivity“, which bothers her a lot. She blames the school system which fails in engaging and showing them the significance of education. However, with her voluntary activity as a coordinator of youth activities, Andreea wants to show children that they can make a difference. A look at the statistics shows that government expenditure on education, total (percent of GDP) in Romania was reported at 3.69 % in 2020, whereas the average for the European Union was 5.1 %.

Emigration vs. Gossiping Neighbours

Mihai is a counterexample of Andreea’s description of Romania’s youth. He emphasises how important it is to him to lead an independent life. For the IT specialist and many of his former colleagues, this meant leaving his village near Braşov in the metropolitan area of Transylvania.

Students celebrate in front of their dormitory with drinks, fairy lights and guitars, singing old Romanian songs they know by heart. (Photo: Private)

According to Mihai, those who have left the area are either well-educated individuals who studied in big cities like Cluj-Napoca, Braşov, and Bucharest and found employment there, or those who are less educated and have gone abroad for work. He recalls that roughly a third of his primary school class has already left, and many of his former classmates are now employed as butchers, care workers, and in agriculture, contributing to the economies of foreign countries. Switzerland may also be a destination, as many sectors, most importantly care and health, rely on workers from abroad to ease the staff shortage. However, in contrast, young Swiss rarely consider spending their life abroad, although many spend a gap or exchange year in a different country.

Mihai explains that on top of financial reasons, there are also some emotional ones leading to emigration: “Many young people are ashamed to work in Romania as cleaners, so they prefer doing it abroad. Otherwise, they fear that the neighbours will gossip.” Mihai observes that some emigrants return to their home country with money earned abroad after some years.

Brain Drain

Statistics confirm what Mihai describes: Currently, every sixth Romanian lives abroad. Among them is a disproportionately large number of well-educated young Romanians like himself. For example, in the medical sector, many well-trained individuals leave. This means that Romania pays for their education but eventually ends up with a major shortage of medical staff. Romania’s annual population loss of about 0.7 % seems a severe problem for the country’s economic upswing. Mihai fears that Romanians will not succeed in exploiting the country’s potential. There might be a skills shortage in the future due to its current lack of perspectives for well-educated Romanians. According to a 2021 report by InterNations, the typical Romanian expat working abroad is 38.8 years old, which is younger than the average expat, who is 43.1 years, and usually moves abroad for job-related reasons.

Working Abroad For Future Stability

Teodor moved to Bucharest from a village near Iaşi in the north of the country to attend a four-year firefighter training. He is one of the few who will eventually find a job in rural areas, where job opportunities are scarce and mostly limited to state employment. In 2020, only 12 % of Romanians considered them very good. Despite being happy to leave the hectic capital after his education, he dreams of working abroad to save money and eventually buy a house back home.

“I Want to Change it”

Emigrating forever is not an option for Teodor: “Romania is the middle class of all countries. And the middle ground is always good.” Here, he can study for free and enjoy freedom. He describes how during a conflict with his girlfriend they tried to understand each other. Eventually, this strengthened the relationship. Somehow it is the same with a country, Teodor explains. “Yes, Romania has its problems. But I don’t just leave the country. I want to change it.” He has already started: Teodor uses Instagram to document the clean-up campaigns he participates in, sharing before-and-after photos of public spaces he helps to clear of litter.

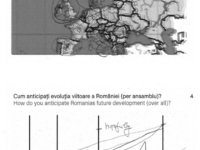

Hopes For The Future

Youth worker Ali doesn’t give up her country either. She is sure that Romania will develop in the right direction, contrary to 60 % of the Romanians who say their country is going in the wrong direction. “I believe in the potential of young people. I know how mentally strong the coming generation is.” Three years ago, she would have preferred to leave the country. But international exchanges and travelling around Europe changed her mind. “I realised that in some aspects Romania is better than other countries. I just love the people and their emotional intelligence here.”

Dear Memories

For sure, I was warmly welcomed in Romania. All the thought- and insightful exchange, the laughter and the joyful evenings are now dear memories. I feel very connected to my Romanian peers as we share many of life’s realities: first time living on our own, studying, concerns about our future and our identities. However, I know I’ve met a very specific – well-educated, urban, young – part of Romanian society. And still, going back to Switzerland, I am more aware of my day-to-day privileges: I can afford to visit a café whenever I fancy a coffee, I have financial stability, a very good and affordable education, and I enjoy a stable democratic system. It is true that travelling not only challenges narratives about foreign countries but also shapes the perception of home.

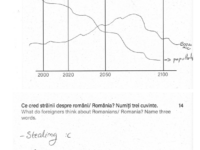

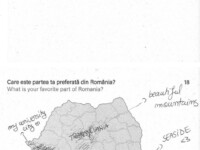

Questions to Romania’s Youth

This text is an extract of the project “Stars for Europe” which consists of photographs, surveys, and a text. To each of Salome’s encounters, she brought her camera and a survey along as a base for discussions. All the above photographs are private.