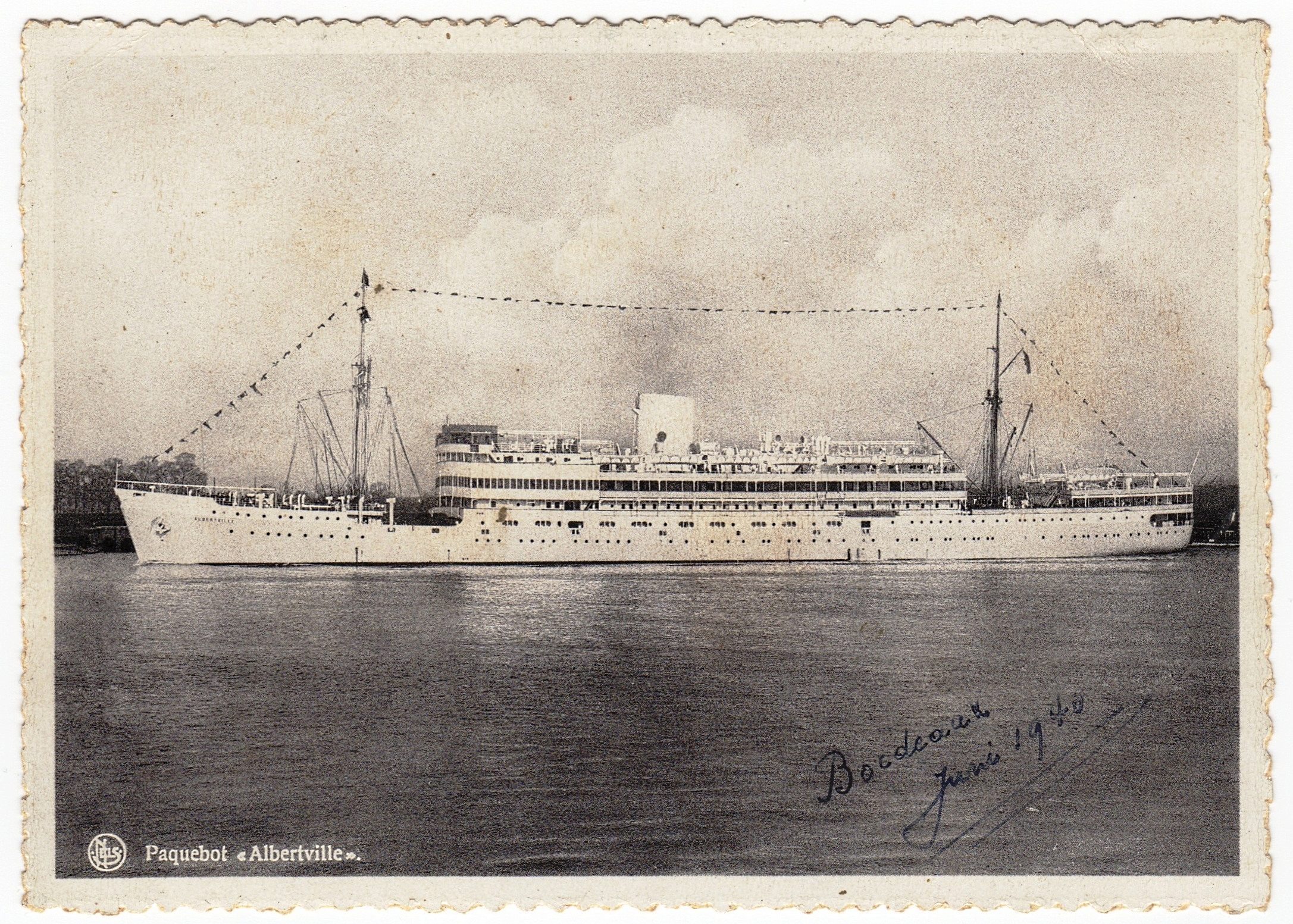

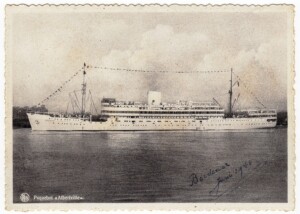

A postcard with the Albertville. The date of arriving in Bordeaux is noted. Credit: Private

Since months the fate of thousands of refugees on boats calls for a European solution. How different the fate of a refugee on a boat could turn out reveals Hilda Ketels. As a twelve-year-old she escaped the German invasion of Belgium in 1940 on the passenger and cargo ship SS Albertville. She told her story to our author Thomas Dirven 74 years later.

“I was born in Gheel, a little rural town near Antwerp, in 1928, grew up relatively happy and had a normal upbringing. I lived a quiet, peaceful country life and my parents had enough money to support our family. My father, Joseph Ketels, was employed by the prestigious ‘Compagnie Maritime Belge’.”

This company was responsible for the shipping between the port of Antwerp and the rest of world. The fleet primarily navigated back and forth Belgium’s colony Congo. Therefore many boats were given names of Congolese cities, for example Leopoldville (Kinshasa), Jadotville (Likasi) and of course Albertville (Kalemie).

Escaping from Belgium

On the 10th of May 1940, when Belgium got invaded by the German army, a crucial decision had to be made. The officers of the SS Albertville had to decide whether the ship should stay in Antwerp, taking the risk of being confiscated by the Germans, which would have been a disaster for the company, or whether they should safeguard the ship and navigate to a port in unoccupied territory with the entire crew on board. The decision to flee was crucial for the lives of several families, including Hilda and her siblings, they only realized how serious the situation was years later, when their parents explained them why they had to flee. So, all hands on deck, Hilda’s father set to sail for Portugal.

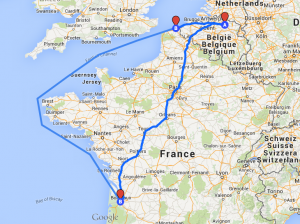

Arrangements were made for Hilda and the rest of her family to take the train to Portugal: “The very thought of being on a ship made my mother feel sick, so we took the train”. On their way, they had fixed meeting points. But when they arrived at the first of these points in Dunkirk, the boat with Hilda’s father had not yet arrived. ”We had to wait for several days, hoping Dad was safe. Apparently our plan was far from fool proof.” Due to the German invasion the ship encountered difficulties to leave the port of Antwerp. The German troops tried to sink the vessel by attacking it with missiles. “Afterwards we heard that the crew on board was terrified and that they kept their life jackets on during the entire trip in case the ship would sink.“

While waiting in Dunkirk, the Germans had laid siege to the city and the train that the family would have taken, had been claimed by the army. So they had no other choice than to go to the port, where they would meet the boat and embark.

This was only the first problem that they had to face on their journey. The original plan was to move the whole company to Portugal and to start all over again. But then everything changed when Franco decided to close Spanish borders, due to his dubious relationship with Hitler. Around this time Hilda was at sea somewhere near Brittany. The helmsmen thought it would be best if they tried to move away as far as possible from the frontline, more precisely to Bordeaux. They were responsible for entire families, so it must have been a heavy burden for them to bear.

Living in a fully equipped floating hotel

“Many of us children on board did not have the faintest idea of what was happening on the continent. I had one younger sister and an elder brother. We lived a luxurious, joyful life on that boat. For us the ship actually was a fully equipped floating hotel.” Because of the boat’s use in pre-war times, to transport people for a period of several weeks to Congo, there were many leisure facilities on board – great for the children. “We could swim, there was an enormous library available and we practised sports in the gym hall. We actually had the time of our life. We did not feel like leaving at all!” They were served every meal in a floating posh French restaurant. The number of people on board was so large that it was not possible to fit all the passengers at one time into the dining hall, so they were used to eat in two shifts, first all the children and then the staff and the captains.

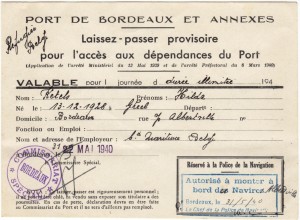

“When we moored at Bordeaux everyone just stayed on board. A few weeks passed, and everyone enjoyed the splendour of the ship and did as if we lived somewhere where war had never existed. Officially the boat even was Belgian territory, so when the kitchen staff went ashore to buy fresh supplies they had to show a French remittance note everywhere they went. My family and I had one, too.”

The German expansion to Bordeaux

Day by day the German army came a little closer, and at the same time the tension in the city and on the Albertville rose. The Germans arrived in Bordeaux, but the ship was already sent to Le Havre. It was used to transport allied soldiers on the North Sea. This meant that Hilda and all the other passengers had to leave the ship and search for homes ashore. In those days Bordeaux was flooded by thousands and thousands of refugees from the north. So it was hard for the people of the Albertville to find accommodation in Bordeaux. In the end Hilda’s parents found a little cottage outside the city, in La Brède, on the same estate where the great philosopher, Montesquieu, had been born four hundred years earlier.

The Albertville was sent back up north, to the occupied territory. The French authorities used the vessel to transport British troops to their homeland. While entering Le Havre, Saturday 11th of June 1940 the port was ‘blitzed’ by German aircraft and the ship sank. There were no survivors. The loss had a devastating impact on the company, they had lost one of their most important and expensive vessels. Hilda’s father was extremely lucky to have stayed in Bordeaux. He got away save, but many of his colleagues didn’t.

“When we heard about this, we were living, together with a friend of my father and his wife, in a small countryside cottage. It was just big enough for all us. The contrast couldn’t be bigger with the splendour and space on the ship. A few months later we were on the train back to Belgium. The Germans had invaded France entirely so there was no point in staying in Bordeaux. Altogether we had been away from home for four months.”

Back in Belgium

When Hilda got back home, her family moved to Mortsel, but the war was far form over, in fact it had only just begun. She suffered from famine and witnessed the bombardment of Mortsel – the biggest airstrike ever in Belgian history. Moreover she had to flee again to her family in Gheel. Miraculously all members of her family survived all of this.

Today Hilda is 86 and lives in a flat in Wilrijk, a suburb of Antwerp. Until this very day she is reminiscent of the times of pure bliss on board of the Albertville. And although she has suffered severely from the atrocities of war, she told me: “You see, Thomas, not all war stories have to be sad.” This remark illustrates quite well, what her fate of being a boat-refugee meant to her – a totally different situation compared to the thousands of refugees in the Mediterranean today. Hilda and her family had the luck to survive Second World War. Many did not, as many refugees today do not survive their attempt of escaping.

Thomas Dirven

Thomas Dirven

(born in 1998) still attends high school. He lives near Antwerp in Belgium. When he listens to people’s stories, he loves passing them on to others. One of the things he certainly wants to do before he dies, is to write his own book.