Have you ever asked yourself what your home is or what it means? And where is it? My family consists of Russian German emigrants and they asked themselves the same questions. They lived in Germany and the Soviet Union just to come back. In the following you will read why they came to Germany again and where they feel home. This is the story of my family.

Germany

This is the Russian-German emigrants’ country of birth. Before they went to the Soviet Union they lived and worked here.

Soviet Union, Wolga

In 1763 Katharina the Great, a German citizen, who governed the Russian empire invited her landspeople to Russia, because many workers and qualified employees were missing. Those who came were promised privileges like land-, tax- and religious freedom. But they were also supported with building up their own industry, plus they and their coming generations were freed from military- and civil service.

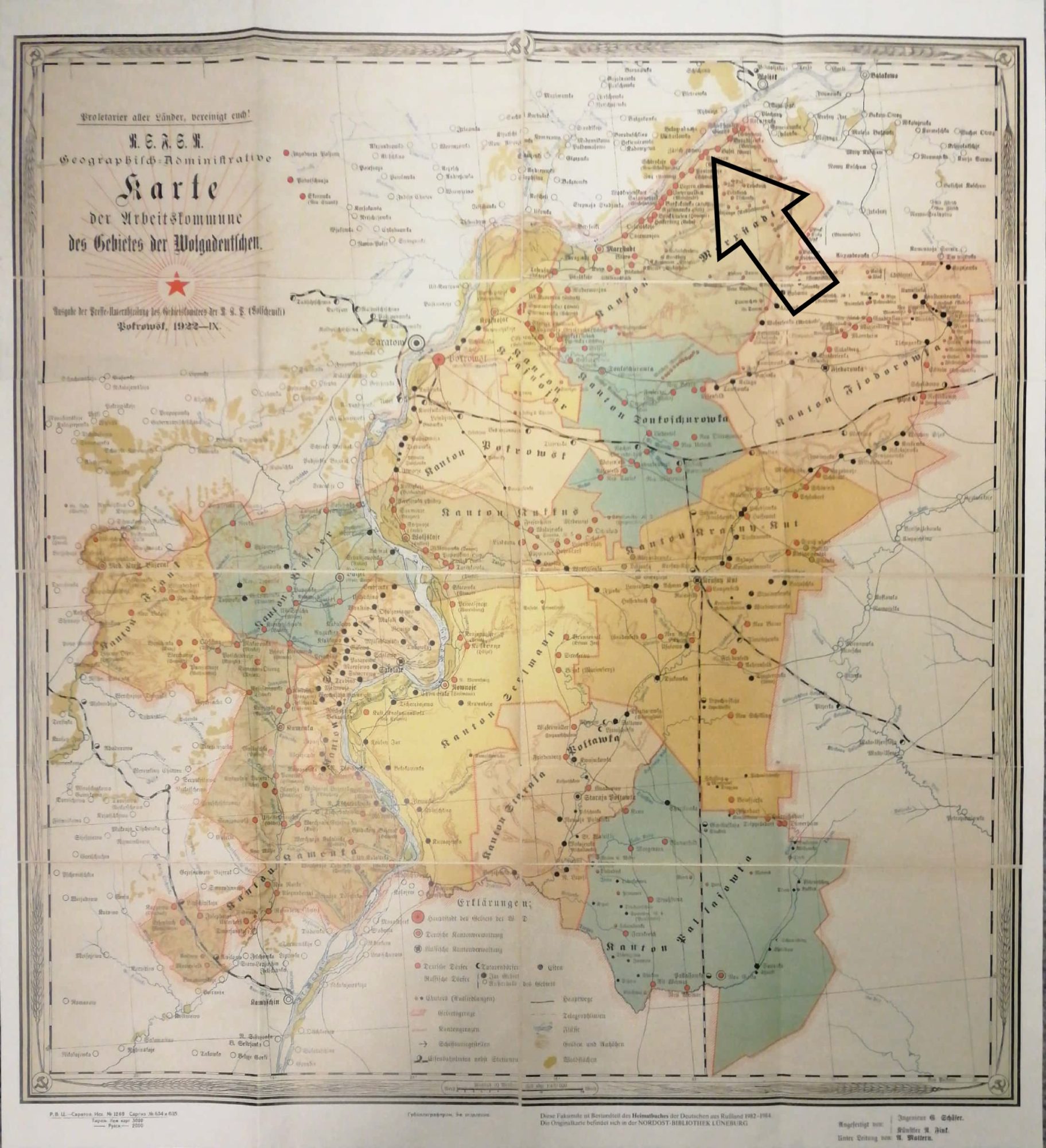

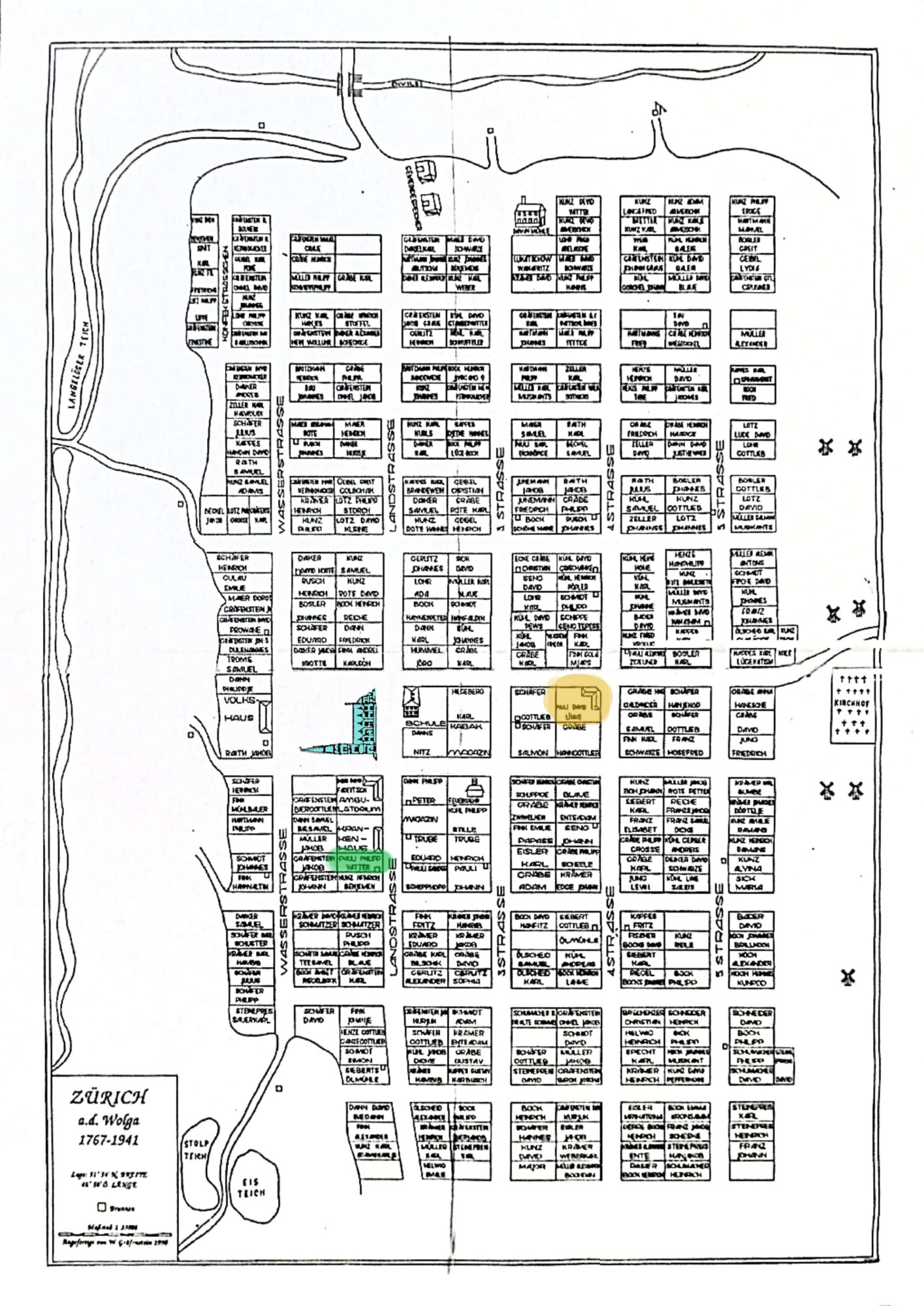

Map of Zürich at the Wolga.

Over decades the Germans lived undisturbed in small villages near the Wolga. That´s the reason the oldest generations of Russian German emigrants are called “Wolgagerman”. Besides they separated themselves strictly after religious confession.

I found a little map of the village a relative of mine, Phillipp Pauli, lived in and marked the location.

As the map says the village was called Zürich, just as it’s example in Switzerland. The next picture offers an overview of the village. Therefore, you may recognize the little building, marked in yellow, having been a pharmacy my family owned.

Map of Zürich.

Luckily this building still exists and you can even find the old medicine cabinets in it. Nowadays the old pharmacy is a little shop. The rectangle in green marks the place Phillip Pauli lived in. Every rectangle stands for a one-family housing. As already said the villages were strictly separated by religious confession so there was only one church per village in where everyone was baptised and confirmed. The one here is marked blue.

1st WW: The Germans were seen as a dangerous group of people and now the state’s enemy of first priority. To protect themselves, the Russians liquidated the Germans and so my family. While 1917 the first 120.000 emigrants came back to Germany my family stayed and hoped for improvements. And they were lucky – Lenin supported national minorities, but this wasn´t for long.

Kasachstan, northern parts

In the 2nd World War, my family was deported from the Wolga into the east; more specifically to Kasachstan. No colony or German village could exist anymore and so they lost much of their culture and language. Before my grand-grandmother died she wrote the following about what she experienced when she was deported:

I was born as the fourth child in a protestant home. In 1936 we were forced to leave house and yard and everything my parents had built in the sweat of their brow. With this, they decided to give up and leave the village. We had to follow the path into exile. We were put in cattle cars in inhuman conditions, and the train set off. But where to? None of us knew, it was clear only – into the east, away from the western border, from our birthplace. I was a six-year-old child then and can’t remember how long we were on the road until we were abandoned in the steppes of northern Kazakhstan. I have not forgotten that we dug a hole into the ground, covered it with willows and straw and hibernated in it.

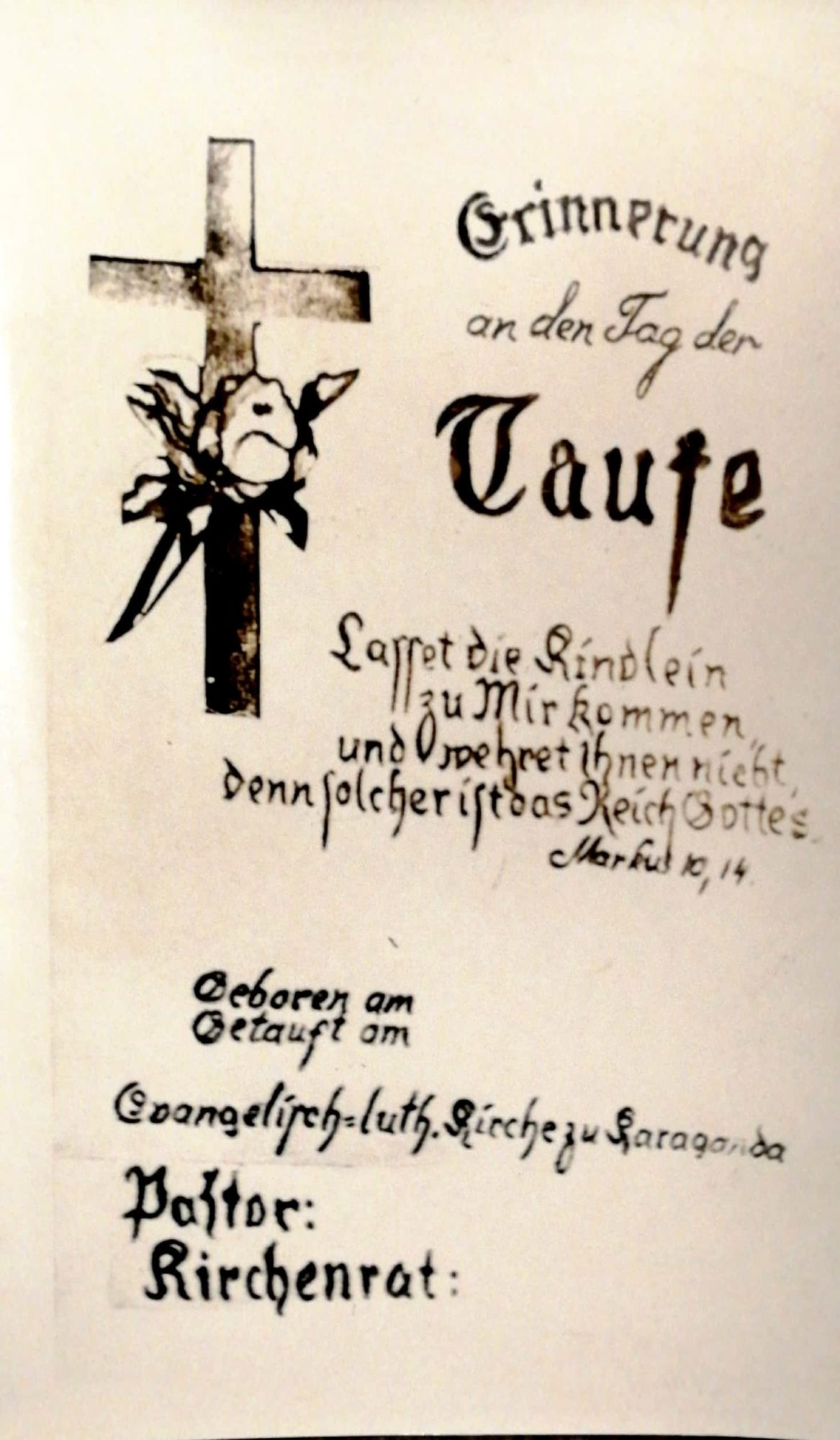

Baptism document

From this day onwards they were forced to stay there. This system was called “Special Command Agency” and included a “Command supervision” as well. Due to this, you had to ask them if you want to qualify yourself or go to work. Furthermore, your freedom to live your religion was taken from you and you were for example not allowed to be baptised anymore. Of course, it happened anyway. And thus, it came, that my grand-grandmother was baptised and the only document left is a photo of her certificate of baptism.

During this time the “Trudarmija”, the labour army, was established and many men, women and teenagers were displaced to work there. My grand-grandmother is so kind and offers us her thoughts on this topic:

After barely a year in the Kokchetaw region of Kazakhstan, the militia took my father away. My two older brothers Helmut and Leonhard said “Dad, why don’t you have dinner with us first?” He said: “Well, I’ll be right back…” It was in 1937, when the “Great Purge” was in full swing. Since that day we never saw our father Adolf Diesterheft again. Sometimes our mother Emilie Diesterheft had correspondence with my father, but apart of that, the letters were simply destroyed there, so that the recipient never got hold of them. In 1953, after Stalin’s death, our father was released due to serious illness and died on his way home. From 1937 to 1953 he was in the camp, for approximately 16 years behind barbed wire, guarded by shepherd dogs. His imprisonment with forced labour was spent by my Father in the north-east, under the most difficult conditions, exposed to Stalinist terror. Nobody knows, where he is buried, no cross, no gravestone shows where his soul rests.

Imagine you would lose a loved relative and wouldn’t even know where he or she is lying.

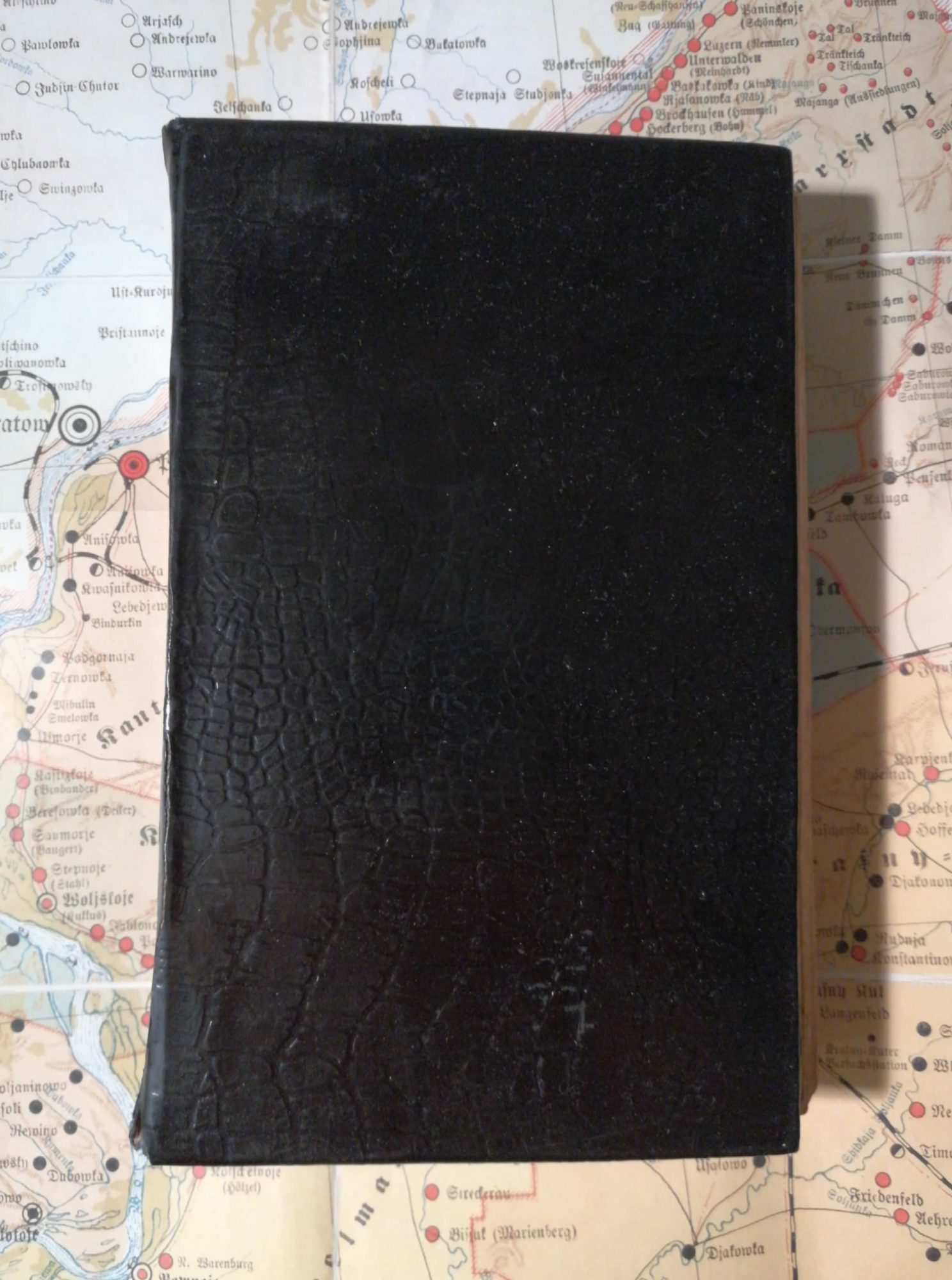

A Christian prayer book.

After the war, in March 1955 the Russian German emigrants got their passports back and in December 1955 the obligation to report was lifted. Although they had to live in their allocated places still and had to ignore their own culture. But my grand-grandparents were of protestant belief and felt the need to celebrate Christian holidays. Christmas, for example, was celebrated secretly. For such opportunities my grand-grandmother had her song and prayer book, which is shown in this picture. This book already existed when my family lived in Zürich by the Wolga (Sorkino), so it can be assumed that the book is around 200 years old and has already been restored a few times but it still looks stable and is easy to read.

Since 3rd November 1972, Russian-German emigrants were allowed to choose where to live in the Soviet Union. An improvement to the current situation then, but nevertheless they missed the freedom they had before.

But what has led to the day, my parents, grandparents and grand-grandparents left the Soviet Union? Of course, the deportations were a reason but not the main, because back then the acting generation had not experienced the deportation and liquidation. What they experienced was discrimination and unfair treatments which had their roots in the envy for the privileges they were given by Katharina the Great.

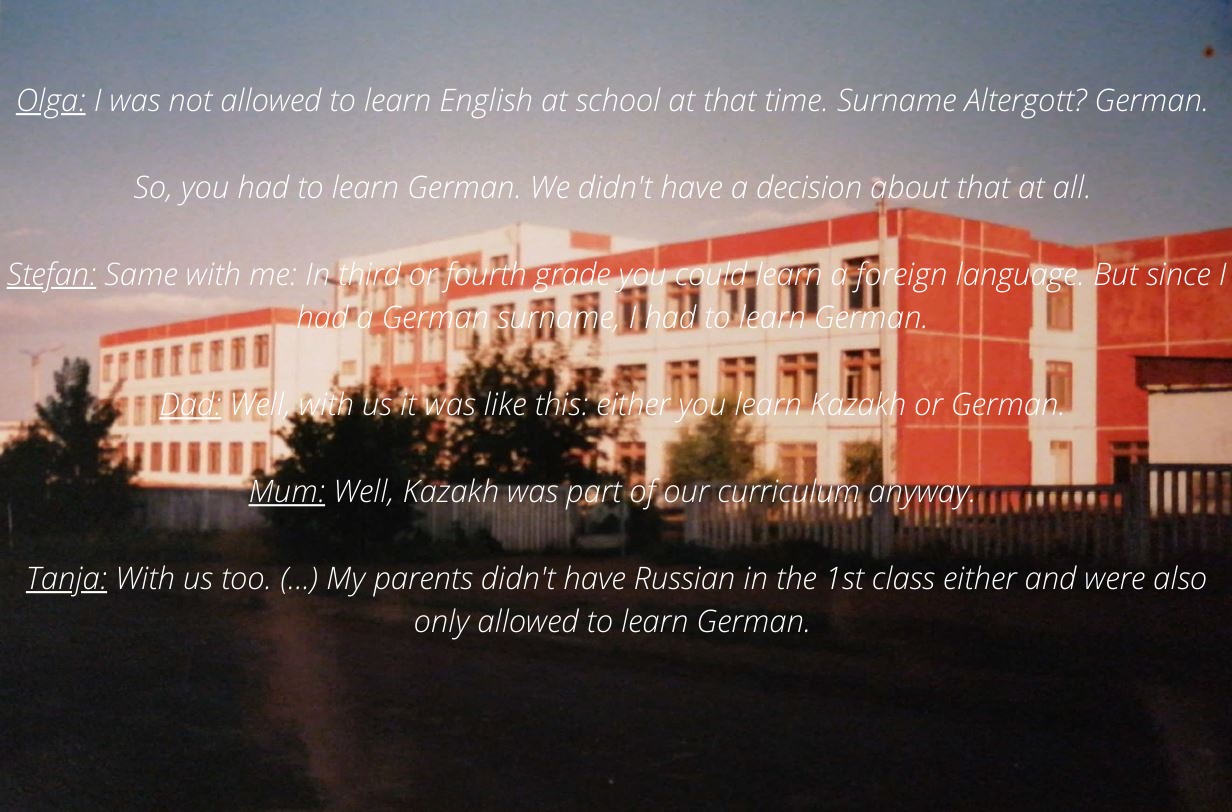

Concerning school, the generation of my parents experienced the following:

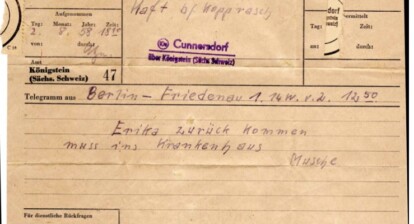

Conversation between differen people of the family.

But also in their daily life discrimination had a great impact as my father told me.

“In front of a supermarket is a number of people, all hoping to get a kilo of sugar. And so it happens that a German comes to the shop counter and asks for a kilogram of sugar. The answer: Everything sold out! The German goes and turns around. And there he sees how a Russian asks for sugar and under the counter a packet of sugar is pulled out.”

These are only two examples of discrimination against my family. And after so many decades under such conditions they wished to come back to the unknown Germany. When 1991 the Soviet Union was dissolved, they finally made the request for an entry permission.

Germany, North-Rhein-Westphalia

And after many force-dragging processes they got it! Now they were allowed to go back to Germany – their home country.

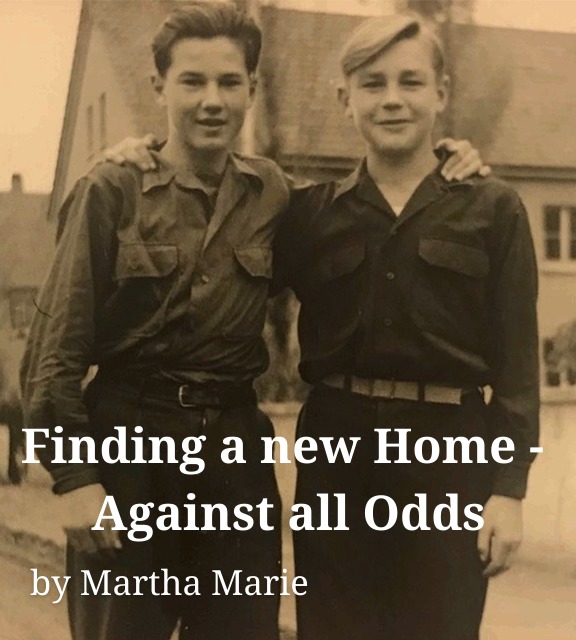

Family arrival in Germany.

The country where you can buy anything and where everything is a perfect paradies! At least this is what they were told. Nobody told the coming Russian-German emigrants that discrimination would not stop at the borders.

The fact Russian-German emigrants got a German passport immediately stroked many natives. How can someone living in the Soviet Union for generations get a German passport right at the arrival? Therefore, my family was not welcomed nicely and did not get the feeling of coming home. Even today my parents call themselves “homeless” although they have integrated themselves in a very positive way. They both work hard and speak fluent German, just as the rest of my family does.

They wanted to live where they could live out their culture without being looked at stupidly and live in the same country where their ancestors lived in. They make many contributions in society but do not feel acknowledged for their achievements. Coming home was their goal and they achieved it partly.

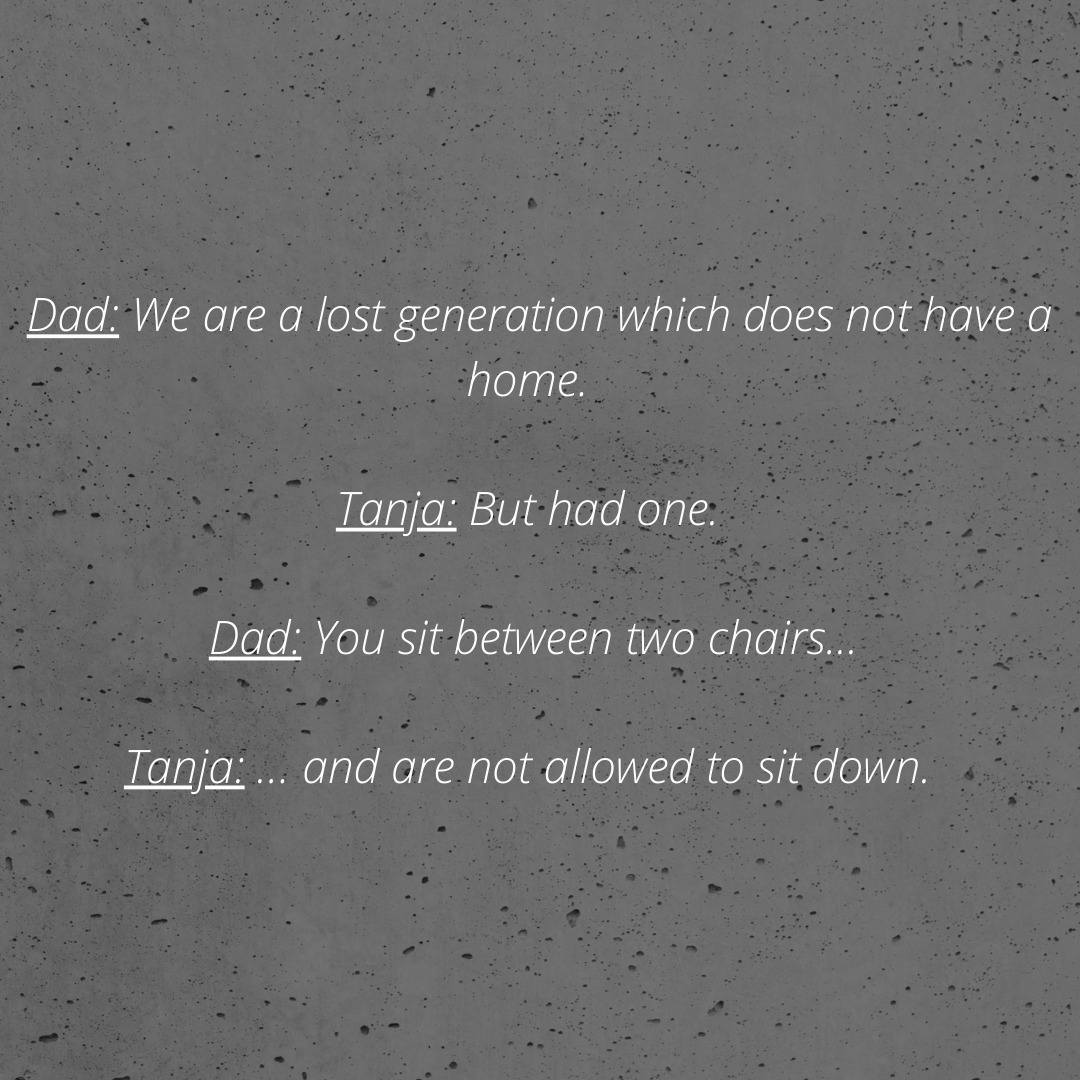

To conclude this story, I would like to give the word to my father and one of his friends:

Conversation between my dad and a friend.