Brief Intro to Operation Pied Piper and The Experience Of Children Who Grew Up in Cities During WW2

“Stories Of Losing, Leaving And Finding A Home”

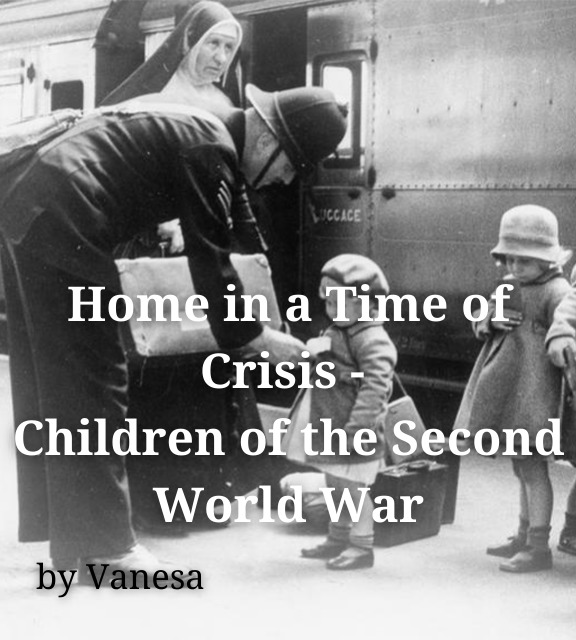

The Civilian Evacuation Scheme in Britian during the Second World. A policeman helps some young evacuees, and a nun who is escorting them, at a London station. Copyright: IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205019036

Stories, we all have them. But, not all of us get to have them heard. History as many of us have probably heard by now, belongs to the victors, or to those in positions of power, so what about the stories of everybody else? This project was made with the intention of bringing the stories of the everyday person to the world. It is specifically focusing on the experiences of children during the Second World War and what home meant for them and what their experience was in their time of crisis.

On the 1st of September 1939, when news of Germany invading Poland reached Britain and two days before Britain declared war, the British government created “Operation Pied Piper” and was put to work on the same day. The objective of “Operation Pied Piper” was to ensure the safety of those in towns at high risk of being bombed, the operation concerned itself with children, pregnant women and others who were vulnerable. The operation was stressful for not only the children being sent away but also the parents left behind. Many parents at the time didn’t know where their children were being sent to and had to wait days before they were contacted by their children of their thereabouts. For many children their new homes weren’t ideal either as the family who took them in was paid by the government to look after them. But as it is always the case, with the bad there is also the good! Some of these children who were evacuated were able to be sent to their family members in the countryside or even had the opportunity to lead better lives. It is important to note though, that this evacuation, especially of children, was not compulsory and in many cases was largely left up to the parents’ decision. So here below are three stories of different experiences; those who were evacuated or those who stayed on the Homefront during the war, kindly shared with me by some people which I have interviewed.

Adele’s Experience At The Homefront

Interviewed on November third, 2020.

Adele was eight, going on nine at the outbreak of WW2 and grew up in Wembley (London-England).

What Does The word “Home” Mean To You?

“Home” to me means where ever I am living at the time, sometimes on wheels. I came back from California eighteen months ago, being there for eight years. I have traveled widely and often and lived in a few countries for short periods of time, including Israel. I came back here to die as I have paid for my plot in the Jewish cemetery, but not yet. Not for a long time, there are still so many things I haven’t done yet. I was planning a big party for my ninetieth in December. Every time I make plans, God laughs and they don’t happen. That is life and I am happy.

We had known there would be a war as my father was sent to Hampshire to build army camps in 1938. We had family connections in Berlin so were concerned for them too. We listened to the radio for uplifting words and the need to pull together to succeed. We felt safe when there were gas masks supplied and we obeyed the order to never go anywhere without it. The one for the baby was like a little cradle her whole body was put in and so not easily portable. She graduated as she grew, to have one with a red flappy nose on it. My mother had told me in 1938, when Kristal night happened, not to let anyone know I was Jewish, which I did, sometimes not convincingly. My father wasn’t Jewish and we were quite sure at the beginning that Hitler would cross the channel.

My father had planned to send us to Canada until the ship full of children was torpedoed and no one else was able to go. I don’t think there was a safer place to be evacuated to anyway. Lots of boarding schools were evacuated en masse, we were left to our own devices. Lots of the evacuees came home during the quiet period at the start of the war anyway.

My father was absent most of the time and my mother had a new baby [born April 1940] which meant I had the responsibility of looking after my three brothers, being the eldest. When we were at home and the air raid siren started we all gathered under the stairs. The gas meter was poking my bony back. It was difficult to sleep there. Other people would go to the shelters on the street or the underground for shelter but my mother didn’t feel up to managing all of us on her own. Eventually we were supplied with a table shelter and we were able to sleep squashed in there. As the bombs dropped the house would rock on the foundations and it was terrifying. I learned that we had to live in the moment to enjoy life as we could be dead by morning. At school we were in the dark in the shelters built where the swimming pool had been. We sang a lot and did mental arithmetic and played other mental games until the all clear signal sounded. If a classmate was absent we thought the worst had happened overnight. We seemed to be in mourning a lot.

Rationing! You have no idea of how little food was available, it was my job to go to the co-op every Saturday morning and buy the rations. That meant queuing up at each department for our one egg a week each, one ounce of butter, two ounces of margarine, about two ounces of cheese and the equivalent of a lamb chop each for the week. Milk was delivered to the door, bread was not rationed but not always available. The greengrocer came by with a horse drawn cart twice a week, the rag and bone man still came with his donkey and cart every week. He paid us for what he would take. The horse droppings were a treasure scooped up by folks growing veggies in the back yard. Many people started keeping chickens or ducks or rabbits for food. My mother didn’t. She was too busy with us and sewing our clothes made from old clothes cut up. Clothes and furniture were also rationed. One pair of shoes a year. We didn’t lose our home but saw other houses bombed on the way to school and the ARP trying to find living survivors. Families from the East End were billeted in vacant houses on my street. They were blamed for the head lice that were running rampant.

After the war meant rationing went on so only the fear of death went away. My mother had never wanted to stay in England and we planned to emigrate to New Zealand until they closed the borders to families, so we went to Canada instead. We left in July of 1949, to Calgary, and suffered culture shock. We were not made welcome. We were wearing strange clothes and had an unusual baby carriage so were cursed and spat on downtown. “Go back to your own country, rotten Deepees.” A young woman at the Robin Hood flour mill, where I was working in the lab, told me I would end up marrying a Canadian chap and so deprive a girl the chance of a husband.

Heather – A Story Of Evacuation

Interviewed on 29 October 2020.

From Liverpool to Tyn y Cefn, Corwen North Wales

What Does The Word “Home” Mean To You?

Home to me is very important. I did travel abroad for many holidays because I like learning foreign languages and eating foreign food, but Home is where my heart is. I loved travelling to Scotland and in Wales, walking and staying in farmhouses and bed and breakfast but I am now quite content not to leave my home!

In 1940 or 1941. I think my parents took the decision when the bombing was so heavy in Liverpool, across the River Mersey. We watched the German planes, caught in the searchlights and being shot at , from our Anderson shelter in the garden. During the days we went out collecting shrapnel from the streets, and seeing the bombed houses.

I was about 10 when I was evacuated with my mother and younger sister to Tyn y Cefn, Corwen North Wales. I think my mother knew where we were going as my father had some distant relatives nearby. My mother, younger sister and I were together, moved to Tyn y cefn, near Corwen and my elder sister was moved with her school to Oswestry. In Tyn y Cefn we shared one room of the house, and had a double bed, I think.

In Junior school in Corwen we were taught in one big classroom, where two classes were taught by the headmaster and the female teacher. In the morning, lessons were in Welsh and in the afternoon in English. We walked to school in Corwen, often in very deep snow. There was a big boiler heater in the room and I remember the teacher feeding us on hot soup when we had walked through deep snow drifts. I remember the head master showing us how to draw an open book, by demonstrating on the blackboard. I took the equivalent of the 11 plus exam with one paper in Welsh, which I passed (simply because I had picked up a few words of Welsh and learnt to count and to swear and to say the Lords prayer and the language is spelt phonetically, when you learn the rules, so I could read it aloud, without understanding.) I passed the exam to go to Bala grammar school, but instead joined my older sister in Oswestry High school and had a couple of years very posh education as it was a Girls Public day school. I was very happy there.

My younger sister stayed in junior school and she and I and my mother moved to Ruthin, where we stayed in Railway Terrace, by the railway line with a bachelor who was a bit overcome by this influx of women. The lavatories were at the opposite end of the terrace, with keys for residents. My mother worked as a secretary at a garage in Ruthin near the castle and went to church where services were held in Welsh and English alternately. She once sat through a sermon and only realised it was in Welsh when she heard the word (I’ve forgotten it) for ,foreigner, stranger in English. My sister was subject to racism, when she won all the school running races. We both entered the local eisteddfod, in the section for evacuees. (I came last! in the singing, but she came third.)

When I moved to secondary school, I lived in Morda, a mile or so from Oswestry, with my elder sister, with very pleasant people, one an old couple, one a family in Morda, where my sister was with a headmaster’s family and I was with a couple with a young son. We adapted to the changed circumstances and I don’t remember feeling homesick at all. My sister was my security and i just drifted through life, in a good school which had its own guide company. I was too busy learning to feel homesick!

My father, who stayed at home in Wallasey and did fire duty, came to visit us (in his old Ford car). I have photos of of us on family walks, when he visited. We didn’t keep in touch with friends at home, but I remember picking snowdrops and sending them wrapped in wet wrapping and posting to my aunt in Liverpool as a treat for her, because we had many such joys!

As soon as the war ended, we all returned to a house my father had found to rent in Wallasey. I travelled home by train and ferry boat with my younger sister and we both went to High School in Wallasey and my elder sister went to teacher training college in Hereford. I remember realising that my Oswestry high school was much superior to the teaching in Wallasey, with mainly elderly spinster ladies. I knew that in most subjects I was way ahead of fellow classmates!

Neil, A Story Of Two Parts- A Life On The Homefront and an evacuation

Interviewed on 8th November.

Outskirts Of London To Somerset.

What Does The Word “Home” Mean To You?

This is important. As I see the position the home is the most important part of someone’s life. It is where we grow up. As a parent it is where we bring up our children and where they come back to as they advance through life. The expression ‘Home is where you hang your hat’ is apt – it is where you are comfortable and at ease with yourself, regardless of where you were born or brought up. Its location is not static – we are all likely to move from time to time but the end result is that we create a new home but the same sentiments apply. In times of crisis we will fight figuratively, if not literally, to preserve our homes. In times of war we join with others to literally fight for our “homeland”.

When WW2 broke out in 1939 I was three and when it ended in 1945, I was nine. But I remember ration books and my parents Co-Op number, 384941, and some wartime experiences e.g. we had a shelter in our garden, which was shared with neighbours when there were bombing attacks on nearby London. The sirens would go, search lights would be seen flickering in the sky searching for the bombers and gun fire could be heard – meanwhile I would try to sleep on one of the bunk beds, while the adults played cards and talked; sometimes anxiously. The bombers could often be heard rumbling overhead and on occasions firebombs were dropped in the road, causing panic and bringing the ARP (Air Raid Protections) wardens into action. But the worst noise was the sound created by “doodlebugs” – a bomb with wings, thousands of which were launched against London starting in June 1944 – which created a low humming sound, which suddenly stopped and everyone would hold their breath for a few seconds waiting for them to hit their targets.

I recall an occasion when I was unwell and kept at home by my mother. During the afternoon she needed provisions from nearby shops that could be reached by one of two roads leading from our house. In the event, we took the road on the left and as we were walking up the road we heard a doodlebug and ran towards the doorway of a nearby house for cover. As we ran down the path the front window was sucked out – a feature created by these bombs – which narrowly missed us. Little did we know that had we approached the shops by the other road we would probably have been killed, as the doodlebug landed on some farm buildings that we would have reached when it landed, causing massive damage. At the time, we had an indoor shelter under which we sought refuge when the sirens were operated. On returning home from our walk to the shops, we discovered that the front windows had been blown in, with the result that the shelter was full of shards of glass that would have caused serious injury. A second narrow miss! Another close encounter occurred one day when I was walking home from school. I became aware of a plane and as it approached it started to offload bullets. I had no reason to think it was aiming at me but I didn’t hang around to find out. I ran like hell. Apparently at the time, it was not unusual for German planesto offload surplus ammunition when returning from raids.

I remember an occasion when some of my father’s school friends visited. They were all young men that were in the armed forces. One of them was in the RAF and I remember him playing the Warsaw Concerto on our piano. This music was written for an excellent 1941 British film “Dangerous Moonlight”, which is about the Polish struggle against the 1939 invasion by Nazi Germany. To this day I find this music as haunting; it conjures up the intensity of the time: I urge you to Google “the Warsaw Concerto” to hear what I mean – the video is excellent. In the event, my father’s friend – the pilot – was killed in action shortly after the visit.

During the war the use of old-fashioned radios – no matter how crude – provided an important lifeline and brought news into homes and programmes boosting morale. Music lightened the mood and a number of comedy-shows. Doubtless yon have heard of Vera Lynn the English singer, songwriter and entertainer who was the forces sweetheart. She died in June of this year at the age of 103 and remained in the hearts of many to the end. But William Joyce – who was nicknamed “Lord Haw Haw”, a radio personality, was another matter. He broadcast German propaganda to the United Kingdom during the Second World War and was eventually convicted of high treason and sentenced to death on 19 September 1945.

Our house suffered a lot of damage during the war from doodlebugs and more particularly a V2 rocket that landed on a nearby property killing the whole family. I was evacuated with my mother and baby brother, Ian, to Somerset for a while and stayed on a farm (the farmer’s name was Sykes) on land owned by a Lord and Lady Walker. This was a great experience, although I felt out of place at the local school. However, I recall a beautiful sheep dog, a lovely orchard, which produced cider apples and the fascination of seeing wasps being trapped in jam jars. But more particularly, I remember sitting astride a horse and going out with one of the farm hands catching rabbits. We had two bull terriers in tow, which nearly pulled me off my feet if I took their leads. He used a double-barrelled shotgun that used cartridges, to shoot the rabbits, which did not make good eating – you could break your teeth on the pellets!

No, we did not lose our house (/home in the war). It was repaired and at the end of the war my parents sold it and we moved to Leigh-on-Sea in Essex where we lived for many years. Having said that, if one of the bombs had landed on the house, I would have a different story. I do not think my parents move was influenced by the war. Their objective was to live in a nicer area.

When I first started work in the City (of London) not many years after the end of the war, there were numerous bomb sites and pre-fabricated homes (prefabs) still existed. Prefabs solved the post war housing shortage. Between the end of the war and the 1970s, many houses in the UK were built with concrete, often pre-formed, pre-cast sections made in a factory. This was necessary to alleviate the chronic housing shortage after the war. I think immediately after the war was a time for re-adjustment. The anxieties of the war had gone but some people had suffered mentally under the strain. The loss of friends and relatives for many also caused strains. The war established changes in attitudes and, for example, the role of women in society advanced. Many men and women that had been in the services were at home again but some experienced difficulties in returning to the way of life they had enjoyed prior to the war for a variety of reasons. However, the prospects of a new life, without fear, brought back ‘normality’ for the majority. Fortunately my family fell into this category and our transfer to Leigh-on-Sea proved to be a good move.