This is my family’s story during the 1984 coal miners strike.

I come from a family of Coal miners. My grandfather, my great grandfather, my great great grandfather, and so on. They were happy. Earned enough money, had a job. It was a simple life for them. But then the strikes started.

Interview with my grandfather

The first main strike was during 1972 for around a month. 9 January to 18 February 1972. It was cold. And to make matters worse, there weren’t enough coal stocks. The coal that was in the stock went to the power stations to make electricity. Even though most of the coal stock went to the power stations, the stock in the power stations went down. Therefore, these power stations all across the country could only operate for 3 to 4 days a week as not enough electricity was made. My Great grandfather worked in Beynons Colliery, Blaina at the time. A four week strike that didn’t exactly affect my family.

Marine Colliery near Cwm (Credit: roger geach / Marine Colliery near Cwm / CC BY-SA 2.0)

This was the starting point.

My grandfather first started working in the coal mines as soon as he left school at 16 during 1963. His first job was in Oakdale Training Colliery, then later Beynons Colliery. In 1965, my Grandfather changed his profession and joined the army as a parachuter. During 1981, my grandfather returned to working in the mines at Marine Colliery in Ebbw Vale where he worked till 1989 when it closed.

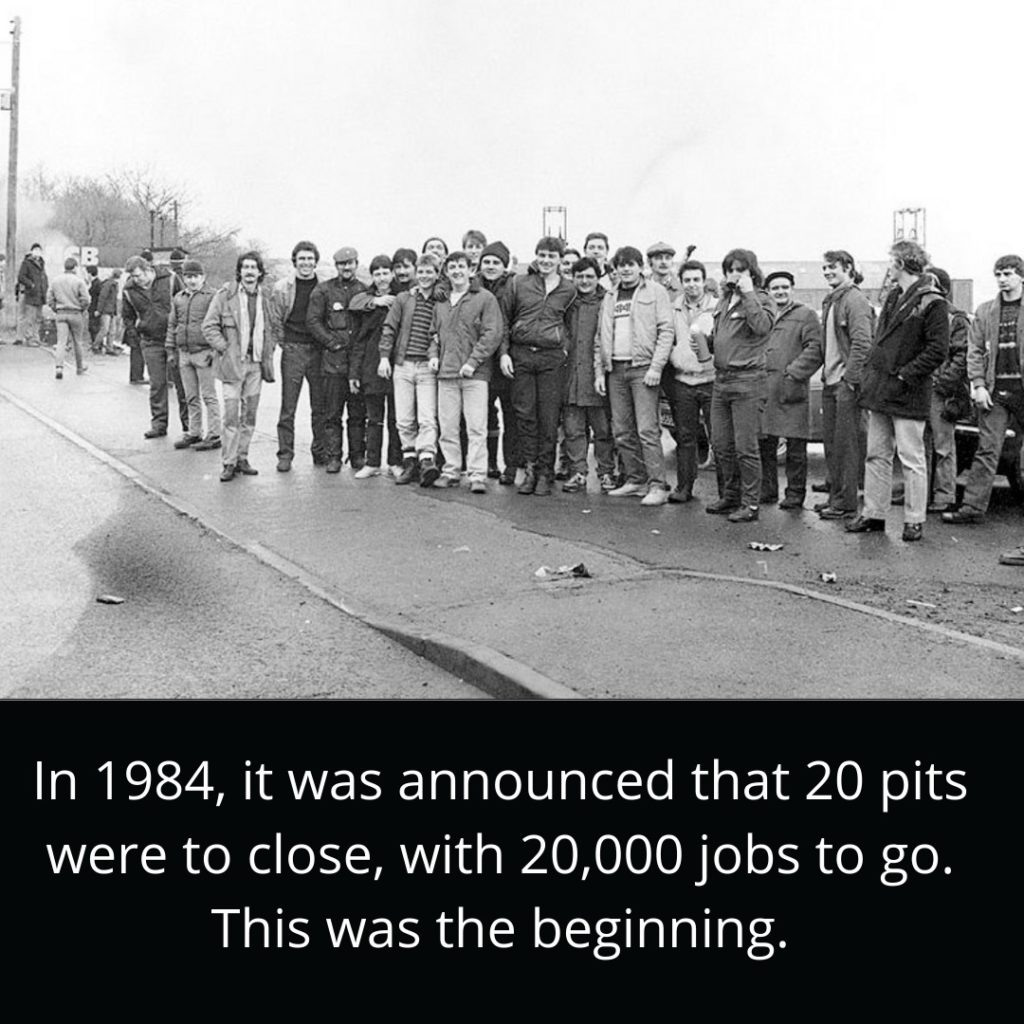

The 6 March 1984-3 March 1985, miners’ strike was a major industrial action to shut down the British coal industry in an attempt to prevent colliery closures. It affected a myriad of people in mining communities all around the UK. In 1984, 20 pits were to close, with 20,000 jobs to go- but more were to be announced. The British Government found it cheaper to import Coal from other countries such as Poland than producing it here.

At the beginning, there were locally-organised strikes across the UK. These were a catalyst to the national NUM strike in March 1985. But, the NUM leader, Arthur Scargill decreed that NUM regions could decide whether or not to strike on an independent basis. My grandfather, he was one of the many miners that took part in this strike. My family was one of the many families that were affected by the Coal Miners strike.

My grandmother was the only person making money during this year long strike, and she was only working part time. It’s strange how you can go from earning enough money to live comfortably to not earning enough money in a matter of a couple days, without notice. They couldn’t pay the bills. They had no solid income. They were struggling. My family almost lost their house. They had to make a deal with the council, a nice and generous council luckily, to pay off their house mortgage once my grandfather got a sustainable job. My family was lucky. Their council was understanding, not only to them but to the rest of the area as well.

With one problem out of the way, my family had to figure out how to use their money and what to use it on. The savings account had to be used for paying bills. The coal board owed my grandfather money, but refused to pay him until he went back to work. So, during the strike, my family didn’t earn enough income, had to queue at the food bank every week and had to rely on other family members.

Compared to other miners, my family was lucky. They barely had any issues with losing homes as did many other miners, only the one scare of losing their house, that the local council cleared up for them straight away. My mother, and many other miners’ children had to have free school meals and queued arduously every monday to get dinner tickets for that week. It was a change.

It was after the strike that became the problem.

A new kitchen was installed in their house, and it was paid off monthly. Because of the strike, they agreed to pay the kitchen off after the strike. Unfortunately the company scammed my grandparents and blacklisted them, claiming they didn’t pay for the kitchen. Luckily the blacklist was paid off, but the fact that a company took advantage of my family when they were at their most vulnerable disgusted me.

Not all miners took part in the strike; some still worked. They were referred to as Scabs. Still to this day no one would bother them, talk to them or even look at them. During the strike, bricks would be thrown at them and names would be called because everyone felt betrayed by them.

Police Officer Point of View

After an interview with a police officer, I have found out how different people viewed the Coal miners strike of 1984. One point of view was that the police were the main reason why most peaceful picketing (protesting) became violent. Another point of view was that illegal picketers and individuals who had nothing to do with the strike caused the violence.

Shows the different sides of the story. Police officer and coal miner.

The miners had a choice. Either work or strike. This was because the leader of the NUM, Arthur Scargill didn’t hold a national strike ballot. Of course, there was tension between the strikers and the ‘scabs’ as the strikers would call the miners still working, and because of this the police had to intervene. The main purpose of the police according to the police officer I interviewed, was to protect the miners that were working. Picketing was a big thing during this time, and sometimes became violent as there was a lot of shoving and pushing. It wasn’t illegal to picket and it wasn’t illegal to still work during the strike. The only way picketing became illegal was when flying picketers travelled to other places or when random people showed up at the coal mines to picket. Which happened a lot.

The majority of the picketers were peaceful and many police officers weren’t actually subject to any violence, but of course there were some exceptions.

In November 1984 David Wilkie, a strike-breaking miner died on the Heads of the Valleys road when two men dropped a concrete block from a bridge on his car. People blamed the picketers as this was an innocent bystander who was killed. It was unclear if they killed him deliberately or not. The police officer said that most violent picketing was up North England and in Wales a lot of police had families and friends who were miners so they were also affected. In reality, the police didn’t want to be involved at all and it was non-political to them. Many people do believe that if the leader of the NUM passed the ballot to hold a national strike, the police wouldn’t have been involved and it would have probably been much more peaceful. But do you think this is true? Or is violence necessary to stand your ground?

Of course the miners didn’t see eye to eye and definitely had many disagreements. What has been written down in history might not be true. What has been written down in history might be true. Each person has their own story to tell and stories differ. You will never see the same thing identically right because not everyone has experienced the same thing.

LGSM

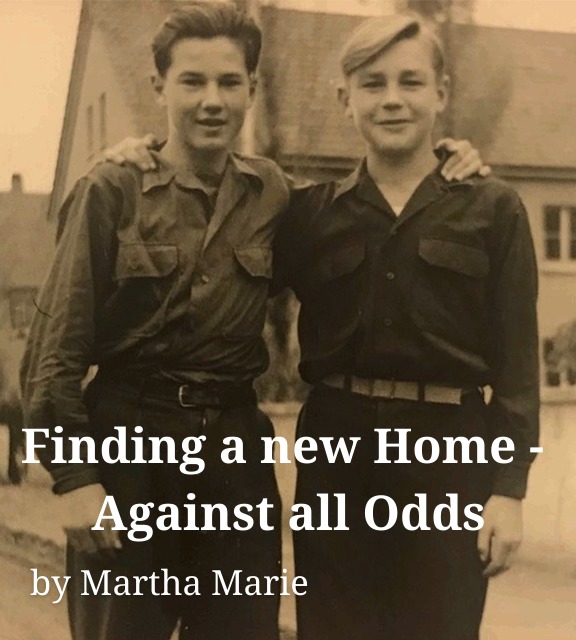

My friend recommended a film to me months ago that was set in Wales and based on a true story. The film was called Pride filmed in 2014, about a group of LGBTQ+people raising money for a small town in the Dulais Valley that were hit hard by the Coal Miners Strike in 1984.

London Pride 2015, LGSM and Welsh miners (Credit: David Jones/Wikipedia/CC).

The founding members were Mike Jackson and Mark Ashton, who organised a bucket collection to support the striking miners during the June 1984 Pride March. At first it was hard to get members, with only eleven people attending the first meeting, but by the end of the strike in March 1985, over sixty people were involved in LGSM (Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners). They raised £22,500 by 1985 (equivalent to £69,000) in support. The money raised helped immensely with the striking miners and their families throughout the duration of the strike.

I watched this film and couldn’t help but feel ashamed and emotional: ashamed because I didn’t know about this movement and emotional because of the heartwarming story of two completely different communities and two completely different views, came together. And not only did the relationship make these two communities stronger, but it was also an important factor in turning the tide in the trade union movement for equality measures for queer people.

The ending of the film was what moved me the most. After everything LGSM did for the miners, raising money during pride parades, from collections at “gay pubs and clubs and on the pavement outside Gay’s The Word Bookshop”, the NUM and the mining communities of South Wales joined LGSM to lead the June 1985 London Pride march. Even after all of this, the NUM supported the call for LGBTQ+ equality at the 1985 Labour Party Conference and Trades Union Congress. It was such a heartwarming and wholesome experience and the film, in my opinion, gave this story justice. It was portrayed beautifully and was an incredibly emotional experience as a whole..

And even today, LGSM members and their banner have led twelve Pride parades across the UK.