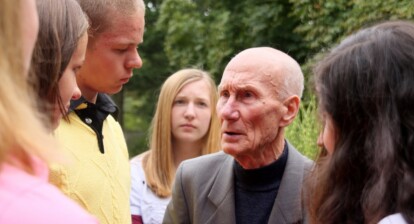

After the wars, more than 400 000 people had to leave their homes. This photo has been taken during evacuations in Kurkijoki in Russian Karelia. (Photo: The Finnish Defence Forces, SA-picture/SA-kuva)

One lifetime has passed since the end of World War II. During the war, Finland was fighting wars of its own against the Soviet Union, first in 1939–1940 and then in 1941–1944. This interview with researcher Jenni Kirves shows that the war is still present in Finland every day. We might not notice it, but the Finns’ attitudes towards alcohol, work and expressing emotions have all been shaped by the legacy of World War II.

World War II ended 70 years ago ‒ that is merely one lifetime. Therefore, it would be unrealistic to assume that the scars – mental of physical – would already have been healed by now. “From historical perspective, something that happened 70 years ago was yesterday. It is an extremely short period of time” says researcher Jenni Kirves. She studies Finnish and Nordic history at the University of Helsinki and specialises in the mental state of the Finnish society after World War II. “If someone says that the war no longer affects us, I dare to argue they are wrong,” she says.

During World War II Finland fought two wars against the Soviet Union. First in 1939–1940 and then in 1941–1944. As a result, Finland lost areas to the Soviet Union and more than 400 000 people had to leave their homes which had become a part of the Soviet Union.

There are still almost 29 000 war veterans. All in all there are about 700 000 people who were born by the end of World War II. Still, the amount of people who are currently in one way or another affected by the war is much higher. It is approximately 5.5 million people, which is the current total population of the country.

Although only few of us carry scars caused directly by the war, every one of us has been shaped by the experiences of those who do. Most of us are children of war unconsciously, as we have absorbed its legacy from our parents – who have inherited it from their parents and grandparents.

We were taught to be good girls and boys

“Parenting styles are easily passed down to the next generation”, Kirves points out. “Often this happens automatically even if one would try to avoid it.”

This is the reason why it may be hard especially for the young generation to see themselves being affected by the war. Our war legacy is no longer clearly connected to the events of the war. Instead, we have inherited the ideals and attitudes which were shaped during and after the war.

Our parents have told us that a good girl or boy is well-behaved and hardworking. They have encouraged us to be quiet unless we have something important to say and made it clear that one should not complain unless something is seriously wrong.

To us, teaching these things is a natural part of bringing up a child as our society values politeness, diligence and being composed. What we might not come to think of is why these characteristics are as appealing to us as they are. In large measure, the reason can be found in the war.

“Those who were children right after the war had the role of preserving their parents’ torments. It was their task to be well-behaved, hardworking and to make sure that their parents had not made sacrifices in vain.”

Also the way in which we express other emotions and behave in human relations can be connected to the legacy of the war.

“Children had to become adults too early after the war, because parents were busy with their work. Mothers did not have enough time to hold their children in their arms when they had to be reconstructing the country,” Jenni Kirves describes. When children did not have the chance to create an emotionally close relationship with their parents, they later passed the avoidant attachment to their own children. They did not learn to ask help from others – instead they learned to manage on their own. “The ideal of surviving on your own is still very strong in Finland.”

This picture has been taken during the reconstruction of the Saimaa Canal. (Photo: The Finnish Defence Forces, SA-picture/SA-kuva)

The Finn’s attitude towards work was shaped during and after the wars.

During the wars, the women had to take care of the men’s work, as well, and after them reconstruction work kept people busy.

Using alcohol as a medicine

Children learn what is taught to them, but behavioural models are also learnt simply through watching and following the actions of other people. The alcohol culture in Finland is a case in point. When men got back from the war, many of them tried to deal with their traumas with alcohol. Although alcohol was consumed in Finland already long before World War II, the habit of drowning ones sorrows in alcohol became more and more common after it.

“Using alcohol as a ‘medicine’ for problems has been moved from generation to another”, Jenni Kirves notes. In addition to creating a large-scale alcohol problem for the nation – alcohol causes about 1 900 deaths annually and each adult consumes 11,6 litres of pure alcohol in a year – the traumas of war created also other unfortunate behavioural models that we are still struggling with. “The traumas also caused violence. It was considered to be the responsibility of the women to be strong and accept all kinds of behaviour from the men when they got back home from the war.”

Stopping the legacy of war from moving to the next generation is anything but easy – mainly because we transfer it to the new members of our society without realising it. Still, it is up to the young generation of this quiet, nice, well-behaved and violent nation of work addicts and alcoholics to do something about it.

“It is our responsibility to deal with our problems and to prevent our children from inheriting them.”

Anna Sievälä

Anna Sievälä

is a Finnish Eustorian who is currently working as a journalist in the city of Joensuu in Eastern Finland. She studied European Law and graduated in 2014. Her life would be empty without travelling, coffee, dogs and – most importantly – amazing European friends.