When Roksolana, student of International Relations in Kiev, started to look for a person to interview she found Dmytro Djula, who was acquainted with her grandfather as they were both members of the contemporary associations ‘Lemkivshchyna’ and ‘Nadsyania’ of the deported people from Ukrainian ethnic lands in Poland.

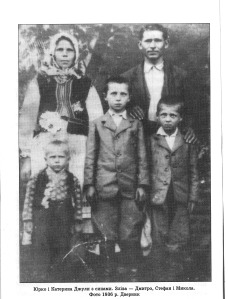

Djula was born in the village Dvernyk Liskiv county not far from Polish-Czech and Polish-Soviet borders. Father Yuriy and mother Katherine, besides him, brought up two sons and two daughters. He finished a primary school in Dvernyk, then during the German occupation attended a school in Lyutovisk.

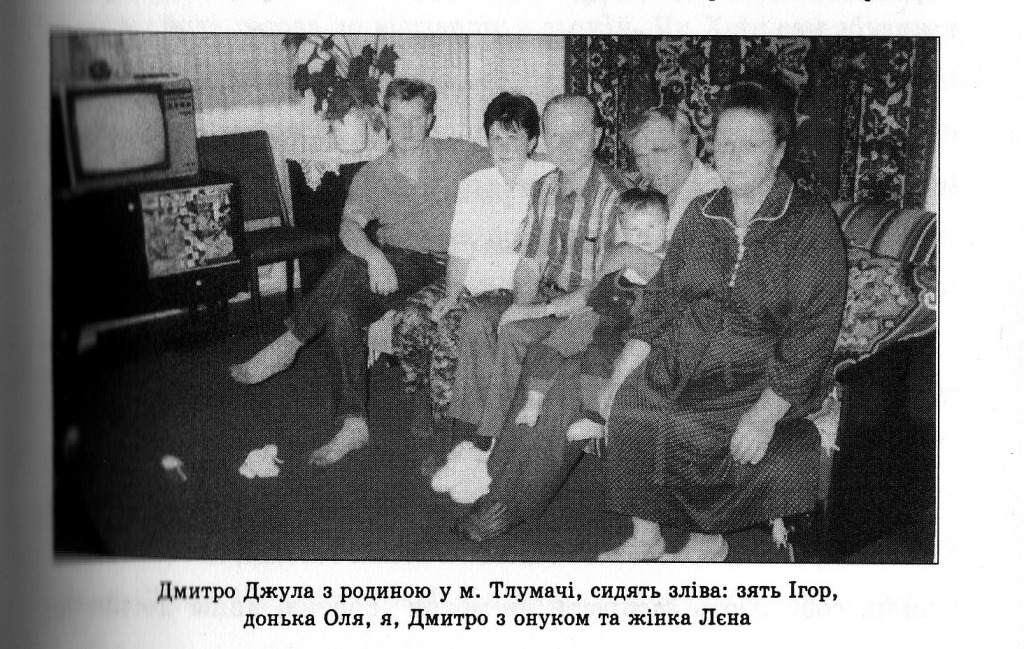

In 1946 Dmytro with his family were deported to Ternopil region of Ukraine, later they moved to the village Nyzhnyv of Tlumach district Ivano-Frankivsk region. There he finished a night school and graduated a trade college, afterwards worked as a cashier. Dmytro got married in 1962, has a daughter and two grandsons.

The life, early childhood of Dmytro, before leaving the native village was carefree. His parents were wealthy, prosperous farmers who owned a mill and a sawmill. Their mills enjoyed the popularity even among the people from neighboring villages. As a result of this, Dmytro thoroughly studied the technique of threshing the grain in order to help his father. Picturesque landscapes of mountains and the river Berezhanka facilitated the recover after the World War II. Over the village for some time there circulated some rumors about the probable migration but nobody knew for sure.

On the 2d of June in 1946 Dmytro’s family and all the inhabitants of his village were deported outside the country of residence under the pressure according to the agreements between the Soviet Union and Poland. It was called the ‘exchange’ of the population. So it wasn’t an exile of good will but a forcible action accompanied by violation of human rights. The ‘deported’ had to leave their place of dwelling, property, household and cattle. The only thing they were allowed to take was the provision. The village was surrounded by hostile armed soldiers who threatened to kill ‘disobedient’ and confiscated everything. However, some families could hide in the forest with the cattle but their fate is unknown.

The immigrants covered 3 km to the border and then 25 km to the nearest railway station on foot. On the border they were registered by the representative of immigration mission who was responsible for Dmytro’s family was appointed to settle in Ternopil region. After that they experienced a two-week trip by train without any extra provision and help, a three-month residence at the station (it was especially hard with sister Pavlina who was six months), humiliating begging in search of food. Finally, the authorities informed they would be given a place of residence in the village Nyzhnyv of Tlumach district Ivano-Frankivsk region but again in the village they settled a

temporary camp waiting for further designations of authorities since it was forbidden for them to settle. At last Dmytro’s family was told to settle in the house of Polish butcher Dashkevych which was almost ruined: without door, windows, only two rooms were suitable for living. They shared the rooms with local host and his family of four members and two teachers. They had lived for two years in such conditions as there were no materials to repair it. In autumn the government divided the field for cultivating but shortly after that there appeared the inscriptions of threats on the door. For local people the immigrants were aliens. But for the priest who lent them an iron oven, they would presumably die of starvation and cold. To make matters worse, postwar famine of 1946 – 1947 gripped a great territory of Ukraine. Not merely the immigrants but also residents had nothing to eat. Meanwhile, the amount of taxes, including food taxes, was overwhelming. Those who were defiant, in particular, their benefactor priest, were sent to Siberia in Russia At that time colectivization as one of the major directions of the policy implemented by the Soviet government was actively introduced on the territory of Western Ukraine. Membership in the collective farms was obligatory so Dmytro’s father gave all the harvest into the collective property not to be pressed and sent into exile once more with his family. All in all, the experience in the new country was bitter. Certainly, in the course of time the Djulas got used to the life in the country of exile and it became their fresh start. They were waiting for returning home for a long time and in 1999 they visited their homeland but in Poland there remained nothing they had, appreciated and loved.

Martyna Ceglińska

great to learn something more about history connected with Poland 😉