Migration flows towards Italy make headlines in European newspapers, depicting the struggles for survival on the Mediterranean sea and discussing the political deals coming along with it. At the same time, other migrant routes receive less attention: In the city of Trieste in Eastern Italy, thousands of migrants arrive via the Balkan route each year. Mawa worked as a volunteer teacher in Trieste and thereby faced new, eye-opening realities.

“Ciudi la porta” “No, mama, chiudi, CHIUDI, con la ch”. As a little girl, my mom called me maestra, which means teacher in Italian, because I always corrected her language mistakes. To be fair, Italian is not an easy language. It must have been difficult for my immigrant mom to learn it as an adult. She left Ivory Coast and came to Italy with my dad at the beginning of the 90s.

As a second-generation immigrant, since my early childhood, I have been very aware of the hardships, the struggles and the discrimination that stem from being a migrant. One of the first obstacles that hinder integration in a foreign country is the language, an essential element of every culture. The language barrier is truly crippling and confusing, especially when it comes to basic everyday interactions. I know how hard filling papers and bureaucratic procedures can get when one does not fully understand nor speak the language. Relying on other people can often feel frustrating.

Becoming a Volunteer

Language is the key to understanding the new environment of a country, necessary to go the first steps of a new life. That’s why I decided to join the volunteering association Linea d’Ombra in Trieste for teaching migrants. Due to my personal experience as a child of migrants and also as a foreign languages and translation student, I thought I could bring a new insight into the approach with teaching migrants. Even if I do not share the burden of being a migrant myself, I know how discrimination and being perceived as a second-class citizen by Italian society feels like. It feels like screaming in silence, because migrants don’t get to have a voice. Linea d’Ombra offers migrants a pen, a notebook and teaching lessons by volunteers to provide the invisible with a voice. An Italian voice, to make them heard and encourage integration into society.

At the time, between spring and summer 2023, I was completing my bachelor’s degree in Trieste. Trieste is a city in Friuli-Venezia-Giulia, in the far east of Italy. It’s the first Italian city in which many migrants from the Balkan route arrive after months, in some cases even years, of tiring travel through countries like Turkey, Greece and Macedonia.

The Balkan Route

Facing the Hardships of Migration

Migrants could attend Italian teaching lessons from 10 am to 12 am, Tuesday through Saturday, at a day centre. They could also eat breakfast, charge their phones, shower and shave their beard. These services were crucial, especially for those waiting for an empty spot in the reception centres for asylum seekers.

Months later, I was shocked to discover that some of my best students (intelligent, funny and clever men) were homeless and living in awful and unspeakable conditions. They were sleeping in a run-down, abandoned ruin near the train station. Moreover, they were bitten day and night by insects, surrounded by trash, rats and cockroaches. While talking with one of my students about their situation, he told me: “We do not tell our family that we are homeless. They would suffer knowing that we sleep on the street. We take pictures in front of nice houses and we tell them that it’s our house, we don’t want them to worry.”

Never Losing Hope

According to Italian and European law, in theory, everyone in the country has the right for healthcare, shelter, freedom and life. In practice, reality is very different. It is evident that my students neither had proper healthcare nor the freedom to live a decent life.

One day, I confronted a very harsh, enrooted bias that we carry with us. I felt deeply sorry because I knew them, because I knew their stories. They did not deserve to live such a life. Of course, no one does, but when it happens to someone close to you, the gravity of the problem hits home. I only cared because I considered them as people, and not as migrants or homeless people. I felt helpless, I had a gut-wrenching feeling hearing about their situation. Still, despite that, they came to learn Italian every day with a big smile and I loved that. The day centre was their only chance to speak to Italians, better understand our culture and try to make sense of their new world.

My First Lesson at the Centre

Let’s start from the beginning. It was my first day as a teacher. I was excited and eager to start this new experience. The room at the centre was not big and it seemed even smaller due to the number of people that were there. It was noisy and confusing and I felt slightly overwhelmed and intimidated.

I did not expect there would only be men of all ages, but not a single woman. I had to wait months until I saw migrant women in the centre. After hearing some of my students’ stories, this gender ratio is no surprise. Since the trip to Europe is so burdensome and expensive, it is considered that men in the family can better handle this gruelling venture. Then, once the residence permit is acquired, men can legally work in Italy. They eventually bring the rest of the family if they wish to do so. Or simply support the family by sending money abroad.

My Volunteering Supporters

Luckily, I was not alone on my first day. Other volunteers took me under their wing and that morning I somehow felt an unshakable energy during those two hours. My first day went well, so well that I began to question my belief of not wanting to be a teacher in the future.

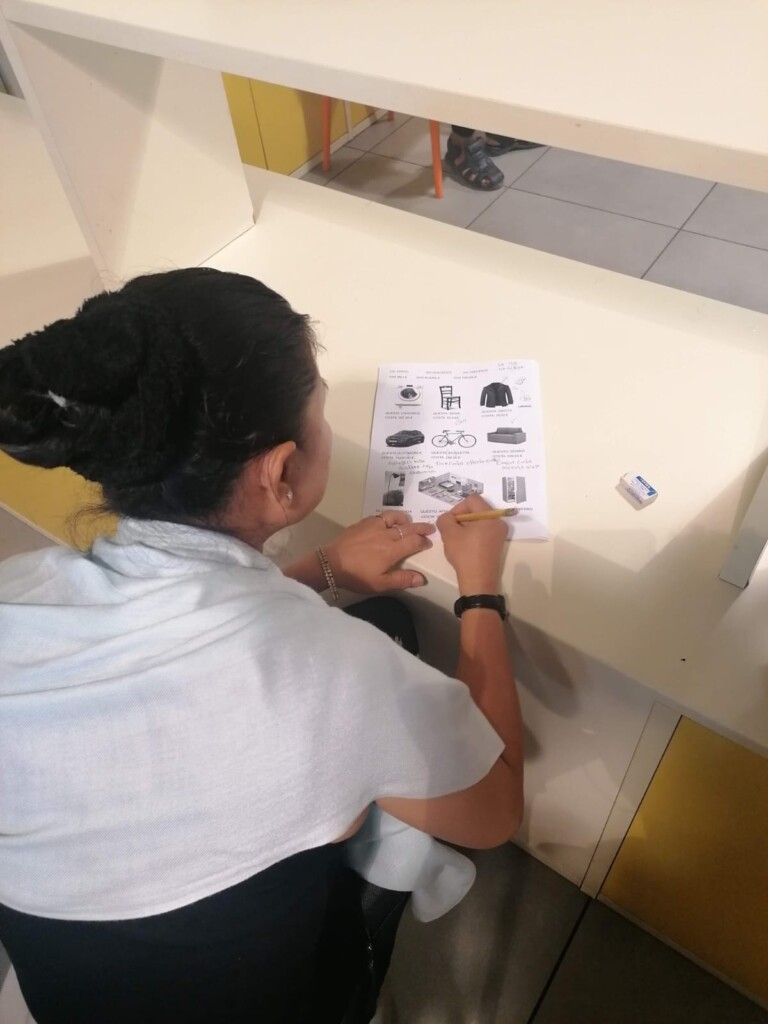

We were teaching basic Italian to the migrants, from the alphabet to the numbers, greeting expressions and fundamental vocabulary. However, I had some eye-opening realizations from the first two lessons: there’s nothing of the Italian language and culture that I can take for granted and there’s so much that I can learn from non-Italians and their languages. I now chuckle thinking about how I was trying to explain what Nutella is.

Beyond Pens and Notebooks

I quickly realized that my “Teaching migrants”-mission went beyond pens, notebooks and whiteboards. Not only was I dealing with students, but also with resilient men and women. People who left everything to take a leap of faith in a whole other continent, hoping that on this side of the world things would get better for them. During the lessons I saw so much potential in some students, so much desire to learn Italian and smash the language barrier. I was proud when they got the answer right, excited when I saw some progress the next week, and thrilled when they asked me to correct their notebook.

Quickly, I became emotionally involved in this activity, in their lives, asking for updates about their paperwork situation or a simple “ciao, come stai?”. Everyone knew me and I knew most of them, and we became friends. I still kept contact with some after they left or were displaced to other reception centres in Italy. The other side of the coin is the heart-breaking truth: no one stays there permanently.

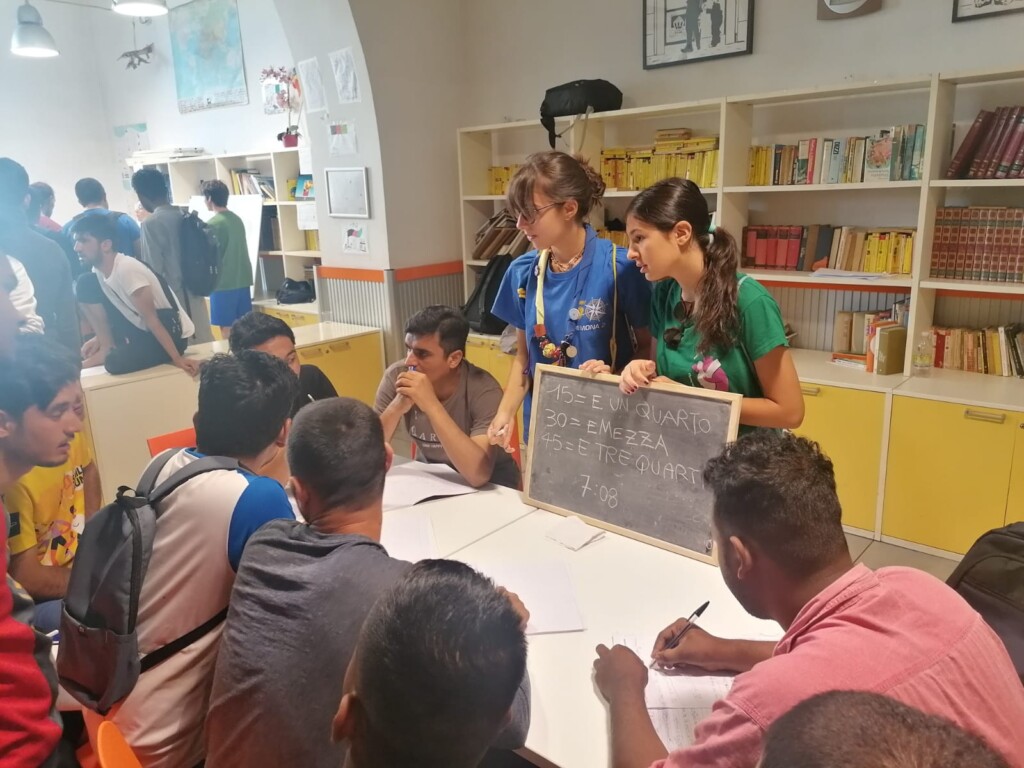

Some scout volunteers and I teaching the time in Italian. (Photo: Private)

“I Thought it Would be Easier in Europe”

Reception centres in Italy cannot accommodate the vast numbers of migrants due to the lack of proper infrastructure and funding. Therefore, they displace them through the country’s reception facilities as soon as other spots are available.

I remember the first time they abruptly transferred a good chunk of my students. Until then, I had no idea how much a transfer could affect me emotionally. First I just wanted to cry, felt guilty that I did not say goodbye to some of them, that I got attached to them, and that I did not exchange numbers with them. I even felt guilty that I was upset, because they were the ones being transferred, losing friends, and stability, thrown into a confusing and inefficient migration system, and unable to predict when they would finally find a place to call home. After this breakdown, I completely changed my perspective, reframing my role as a volunteer. I tried to make the most out of these interactions as if every time was the last time I met them, because I now knew that eventually the day would come.

Some opened up to me, because at the end of the day, they were only looking for genuine friends, mutual understanding and kindness. The recurring theme that would come out of our conversations was that they thought that it would be easier in Europe. Never in a million years would they have imagined being homeless, having to endure social discrimination, unfair treatment, isolation and the struggle to acquire paper as an asylum seeker in a migration system that has ridiculously flawed policies. What they imagined as a garden of Eden quickly became a living hell.

A Volunteer, a Teacher and Also a Friend

We volunteers were trying to give back some dignity in a society that stripped it away from them. Our help with the migrants went beyond teaching Italian: we would join them on the square near the train station where migrants gathered up because they had no better place to go. They could get some basic healthcare, food and other essential supplies there. We spent afternoons and evenings with them, playing cards and other games, singing and playing volleyball. Sometimes some of my students would even ask me about the lesson we had in the morning. I genuinely felt loved, they showered me with compliments, they always told me that I was a good teacher, and I truly believed them. I think it is because I knew better than other volunteers what they needed. Or just because I would always smile and laugh during lessons. Probably a mix of both.

People, not Migrants

In the first lessons with newcomers, I would stress the importance of knowing how to spell their name. I’m quite familiar with how frustrating it is when people write your name incorrectly. I would always jokingly say that I have seen my name butchered in so many creative ways in 20 years. A simple letter spelt wrong may endanger the whole paperwork process in a system that is already trying to find any viable way to make procedures more confusing and complicated.

It was my third year living in Trieste and these people had been invisible to my eyes until I joined that volunteering association. For years I was blind because I did not want to see this truth, the uncomfortable truth of the neglected and marginalized. I never bothered to ask what they were doing in the square, and who were those people helping them. For me, I just considered them migrants, stripping away the inherent humanity that they possess. Now I do know their names, their faces, their stories. Everywhere I went I would meet at least one of my students and many would greet me with “Ciao maestra!”. They went from being the umpteenth migrant to being my students, my friends, my people.