For a language that was so close to extinction in the past, Irish simply refuses to lie down and play dead. Neasa from Ireland talks about the reasons for this as well as young people’s attitudes to language and culture, and the compulsory status of Irish in schools.

Growing up with Irish: A Love/Hate Relationship

As someone who grew up in Ireland, I was obliged to learn our native language in school. However, while speaking our national language is seen as a living expression of our national identity and soul, the compulsory status of Irish in schools, and the way it is taught, is not always ideal. This often results in Irish people having a love/hate relationship with the language. This prompted me to explore how other young native and non-native Irish speakers feel about Irish. But first, here is a little background information.

Exploring the Roots

Irish, known as Gaeilge to most people in Ireland, is part of the Celtic language family and has existed for over 2000 years. After the Anglo-Norman conquest in the late 12th century, hundreds of years of conflict ensued during which the Irish resisted British authority and colonialism. One of the lasting effects of this colonial influence was a dramatic decline in Irish speakers, beginning in the early 17th century. During the 18th century, many rural Irish-speaking communities began to adopt English as their first language. This was because most people perceived Irish as redundant and backward. Parents discouraged their children from speaking Irish, because it was seen as a language of the poor.

Facing Decline and Resurgence of the Irish Language

The Great Famine (1845-1850) also severely crippled the Irish-speaking population living in poor areas, as many died or emigrated. People lost interest in Irish, particularly because those who wanted to emigrate to America or England needed English as their first language instead. The language was on the point of extinction. However, towards the end of the 19th century, a mass movement of support for the Irish language emerged. Renewed efforts were made to revive and preserve it during this time, and have continued to the present day.

Current State

According to Ireland’s Census 2016, 39.8% of the population could speak Irish. My home county, Galway, had the highest percentage of Irish speakers of all the counties in 2016, with 49% of the population claiming that they could speak Irish. But I also learned that only about 4% of the population use Irish on a daily basis outside of education. This section of the population was found to be better educated than the general population. Around 49% of this section of the population boast a third-level or higher education, compared to just 28% of the general populace. Furthermore, about a quarter of the Irish population say that they cannot speak Irish at all. Although a minority language, it is also an official language of the Irish state as well as English. It is also the only Celtic language that is recognised as an official language of the European Union.

Preservation Efforts

The Gaeltachts, or the Irish-speaking areas on the island of Ireland, are located in seven different counties, including six inhabited offshore islands. Údarás na Gaeltachta, a government-funded organisation, was set up in 1980 to help preserve Irish as a community-spoken language, particularly in these areas. Other initiatives to promote the Irish language included the emergence of ‘Gaelscoileanna’ or Irish language primary and secondary schools outside Gaeltacht areas, in which all subjects are taught through the Irish language. Furthermore, thousands of secondary school students from all over Ireland attend colleges in the Gaeltacht for a few weeks every summer to improve their spoken Irish.

I decided that it would be useful to talk to three of my peers about their experience as young people with the Irish language. I also asked them what they think the future holds for Irish in this country.

The Personal Meaning of Irish

I am well acquainted with two students who grew up speaking Irish in their homes. Christina, who lives near a Gaeltacht island, Cape Clear, off the coast of Co. Cork, said to me, “Irish means a lot to me because I grew up with it. I learned it from a very young age from my mother and older siblings as they are fluent in it. I always had a very good understanding of the language, and I feel that Irish is a big part of my identity as an Irish citizen in Ireland.”

My friend Ailidh comes from Gaeltacht na Rinne in Co. Waterford, so speaking Irish was also a part of her daily life. “The Irish language is a connection to home for me, but it’s more than that,” she told me. “It’s a connection to our culture and our history and it’s a huge part of our national identity as well as my personal identity.”

I also spoke to my friend Hannah, who, like me, simply learned Irish during her years in school and is not fluent like Christina or Ailidh. She did not see Irish as an essential part of her identity: “The Irish language does not hold a huge amount of importance for me personally. I understand that it is a significant part of Irish history and people believe it is important to cherish its role in our culture. However, as it is a largely dead language today, and because it is of practically no use, I would have no problem seeing it dying out completely. Also, as I have 100% Irish roots, I do not need the Irish language to find my identity.”

Should the Irish language be Compulsory in all Schools in Ireland?

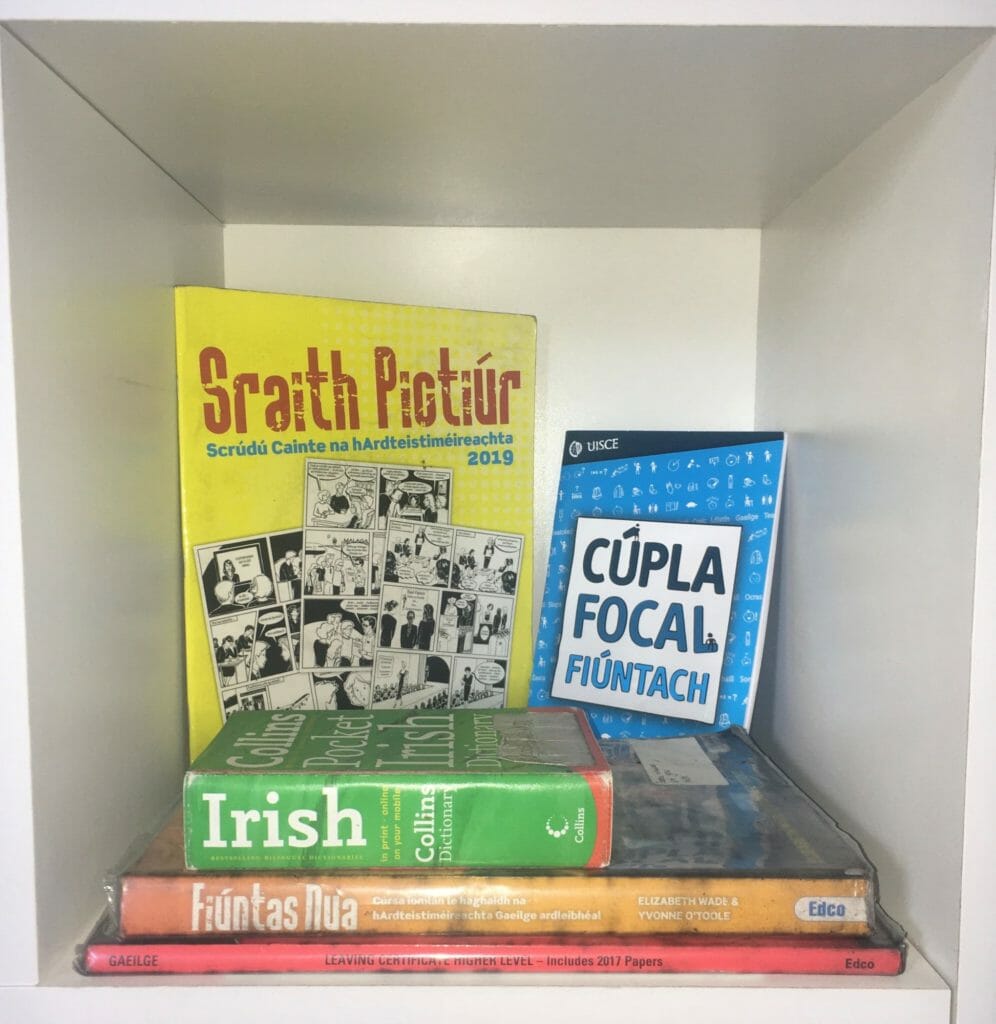

My old Irish schoolbooks (Photo: Private).

There has been a long-standing debate about the teaching of Irish in the Irish education system. It is compulsory for all Irish students to learn it in primary and secondary school, except for those with an exemption due to intellectual disabilities such as dyslexia. But is Irish a necessary exam subject? Or should students be given the choice to learn it?

Ailidh supports the position that Irish should be compulsory: “Irish is our national language. Besides its preservation, teaching Irish in schools gives students access to the wealth of songs, poetry and literature in Irish. I think that removing the Irish language from the school system would be very damaging to our culture and history.”

The Potential Impact

From my own research, I found that if Irish were made non-compulsory, this would cause a huge drop in the numbers of people learning it. Furthermore, it could also close certain career doors for students. For example, Irish is still required by many colleges as an entry qualification. Because of this, the elimination of compulsory Irish from the school syllabus could have a negative impact on the futures of young people.

Others are of the opinion that learning Irish is nothing more than a tedious burden for them. Irish is a difficult language, so it can be off-putting for many young people especially when they are under massive pressure to pass exams. “I feel that Irish shouldn’t be compulsory in all schools in Ireland but in the vast majority,” Christina told me. “The language has survived several hundred years from being the most common language spoken by people at the time. I feel it would be unfortunate if we lost it.”

Hannah had a different opinion: “It is unfair to force students to learn a difficult language if they have no interest in it. I think the language will be of no use to students in the future, as it is not spoken in any other country in the world,” she said. “I believe it should be one of the many optional subjects for students.”

Considering Diversity

When it comes to whether students should be forced to learn Irish, one must also consider all the immigrants coming into Ireland. According to the 2016 census, there were 96,497 non-Irish national students and pupils resident in Ireland in 2016. Should these children, particularly those in their early teenage years, be forced to learn Irish in school, especially since English would not be their first language? Christina thinks that this would be rather unfair. “I think that it should not be compulsory in schools with mixed nationalities who haven’t had a grasp of it from a young age.”

What Does the Future Hold for Irish?

A bilingual road sign near my house in Galway, with Irish place names above the English versions (Photo: Private).

Overall, the future of Irish in my country is unclear. Recent developments have shown that this conflict won’t be resolved anytime soon. The #Gaeilge4All campaign was launched in 2019 to defend the Irish language and to strengthen the subject within the education system. If there is to be a major revival in the learning of Irish among young people, there would have to be huge changes in the way it is taught in primary and secondary education. Irish children attend primary school from ages 5 to 13, and then secondary school for another five to six years. “It’s such a shame that Irish is taught in a way that makes students struggle so much with it. Irish is seen by many as nothing more than a burden or as a dead language that will never need to be used,” Ailidh told me.

In Need of Massive Modification

Hannah thinks the future for the Irish language is very uncertain and concludes: “I believe that the structure of Irish as a subject, particularly in the Senior Cycle (final two years of secondary school), is completely useless. In my opinion, it is in need of a massive modification. I strongly feel that if Irish is to remain a compulsory subject in school, the way it is taught needs to be completely changed. If this does not happen, the future of the Irish language may be very grim. It should be taught much more through conversation rather than through rote learning of poetry and essays. Many students do not fully understand Irish, so I believe that rote-learning serves no purpose.”

Ailidh also made some suggestions about how to make Irish more engaging for young people: “ The language should be taught through mediums that young people will enjoy, for example the Irish pop songs of TG Lurgan. We also need to promote an appreciation for heritage, which includes the teaching of Irish myths and legends, and our culture. I think these are fascinating subjects for so many young people.”

Hopes for the Future

The Irish language also has a strong presence in the media in Ireland, thanks to Irish-speaking broadcasting services such as Raidió na Gaeltachta and TG4 (radio and television channels), as well as printed media. Ailidh believes that these play an integral role in the advancement of the language: “In my opinion, it’s so important to make more media available for young people through Irish. I think it could compete in some way with the music and television shows that we import from England and America.”

Despite the various problems within the Irish school curriculum, Ailidh has high hopes for the future of our native language: “I know so many young people who are passionate about the Irish language, myself included. We all want to promote the Irish language and to keep it alive for future generations. It will really take a lot of dedication and passion to keep Irish alive. However, I do have confidence that it could face a real resurgence under the right circumstances and with the right amount of support,” she concluded. “I believe that Irish should be taught in a way that encourages young people to speak it and helps them see the beauty and rich heritage of the language. Tír gan teanga, tír gan anam.”

The latter is a famous quote by Padraig Pearse, one of the rebel leaders executed for his role in the 1916 Easter Rising. It translates as “a country without a language is a country without a soul”. This phrase still resonates with many young Irish people today, more than 100 years later. We should continue to take these words to heart and do all we can to maintain Irish as a living language if we want it to survive and thrive into the future.

Peter

Really interesting article, language is such an important part of one‘s personal and national identity! Thanks for sharing the Irish perspective!

Neasa

Hi, thank you so much for reading my article! I‘m very happy you found it interesting and insightful!

Carrie

It’s a shattering loss when any language or form of writing is lost. Here in the States we have stopped teaching cursive writing so now these new generations will no longer be able to read original documents; such as the Declaration of Independence. Tragic!

Brigid

I enjoyed reading your article, we have exactly the same problem here in Wales with Welsh. However it is compulsory in schools but is not always taught in such a way that resonates or encourages students to do more than study it as a subject. We also have Welsh medium schools where all subject are taught through Welsh and the Welsh government is pledged to increase the number of such schools. Unfortunately the number of teachers is limited.

Good luck with your research.

Ralph Kilcup

I’m in the view that Irish, thought of

as ancient to some, similar to the way Latin is viewed should be a National Language taught, nurtured along with English to our Children. I regret not being able to. I also am of Irish/Austrian Heritage who’s family immigrated from Ireland during the Great Famine first Canada then to America. Here, you need to select to go to school and pay for the privilege! If it comes to a vote, teach your children well. Encourage it to be spoken. You won’t be sorry!

Katleen Bell-Bonjean

Thanks so much for writing this article, great insights! Best of luck with your course!

Katleen ( living very near Ardrahan)

Neasa

Hi there, I‘m delighted you liked this article! I think Irish is a very important topic in this day and age, so you’re most welcome!

And thank you, I hope my course works out too 🙂

(I actually live near Ardrahan myself, outside Craughwell!)

Howard Edwards

I’m a Welsh speaking Welshman.

Irish being force-fed?

I think it was English that was being force-fed, and that is what has been killing off the Irish language.

Please protect the beautiful Irish language.

Colin Ryan

I just came across this article and read it with interest. I am an Australian Irish speaker (getting on in years now) and I suspect that Hannah’s view with regard to the relevance of the language is widely shared in Ireland – i.e. not hostility but indifference. I actually sympathise with her. The language (as she herself points out) has not been taught in an effective and engaging way and drastic reform is needed. Still, there is now a critical mass of urban speakers.

Derek Hollingsworth

Bhain mé taithneamh as an t-alt seo. I think the argument that Irish is useless is false. There is a vibrant Irish speaking community. In addition there are more areas of employment available in education, media and the civil service

Eugene Mccarthy

My grandmother and my Dad spoke Gaelic but I never learned and now I which I had would like to now but don’t know where to go

Clare Horgan

It’s force fed when we are in school. 15 years of wasted time , not knowing the fun, the meaning, it’s identify and why it makes us. How it has made it into the English language etc. Only when the few take it back up again in adulthood do we realize what could have been.

Pingback: Making Friends with Music - EUSTORY History Campus