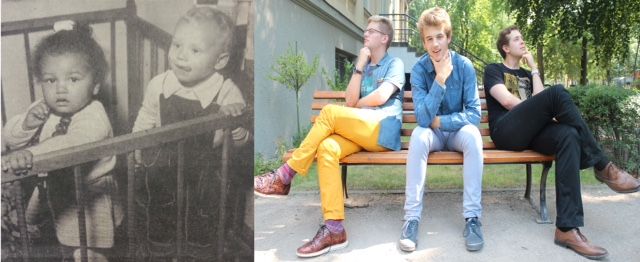

Left: A black occupation child with a playfellow in Vienna. Source: Neuer Kurier, 05 October 1956, page 3. Right : The “Troika”, from left to right: Haris Huremagić (Austria), Thomas Dirven (Belgium) and Jani Patrakka (Finland). Photo: Agency for Education.

MISSING CHANCES – DEALING WITH OCCUPATION CHILDREN IN AUSTRIA

MISSING CHANCES – DEALING WITH OCCUPATION CHILDREN IN AUSTRIA

“You whore’s bastard, I should have killed you at birth.”[i] – 30 000 children were born to a foreign military parent in my country Austria after the Second World War. They were treated as “enemy’s children”, as “bastards”, some, however, but also as beloved children. It depends on how the direct surroundings coped with this phenomenon. The mother, who said the aforementioned sentence, might have been a victim of rape.[PE2] Another occupation child stated: […], I want to thank my family that they never let me feel that I am an occupation-child.

Particularly “black” children were seen as too difficult to integrate them into the Austrian society as a result of a racist Nazi way of thinking. A huge pressure was put on their parent in order to give them away. They were deported to the United States, where they faced racial segregation.[iii] Their mothers faced discrimination and had to bear insults.

Particularly “black” children were seen as too difficult to integrate them into the Austrian society as a result of a racist Nazi way of thinking. A huge pressure was put on their parent in order to give them away. They were deported to the United States, where they faced racial segregation.[iii] Their mothers faced discrimination and had to bear insults.

While the topic of occupation children was discussed publicly in Germany when they started to attend school and thus became “visible”, it was completely “forgotten” in Austria. Why is that?

One of the reasons is that Austria has denied its involvement in Nazi-crimes until the 70ies and that has led to an atmosphere of silence. While there was knowledge of the existence of this group among ordinary people, who talked about it on a micro level, the intellectual level went along with the common attitude of forgetting the past and every topic that could trigger a wider discussion, such as the topic of occupation children. What are the consequences of this denial?

One of the reasons is that Austria has denied its involvement in Nazi-crimes until the 70ies and that has led to an atmosphere of silence. While there was knowledge of the existence of this group among ordinary people, who talked about it on a micro level, the intellectual level went along with the common attitude of forgetting the past and every topic that could trigger a wider discussion, such as the topic of occupation children. What are the consequences of this denial?

Rainer Gries and Silke Satjukow, both German historians, recently published a book on occupation children claiming that they became “catalyzers of a new liberality” and of a “new opening to the world”[iv] . By dealing with the individual occupation child in every day’s life, German people could overcome the Nazi way of thinking concerning “foreignness” – in contrast to Austria. As a result, Austrian society has still not found a way of coping with (alleged) “foreignness” for the last 70 years.

[i] Quoted from: Stelzl-Marx, Barbara (2015): Kinder sowjetischer Besatzungssoldaten in Österreich. Stigmatisierung, Tabuisierung, Identitätssuche. In: Stelzl-Marx, Barbara & Satjukow, Silke (Eds.). (2015): Besatzungskinder. Die Nachkommen alliierter Soldaten in Österreich und Deutschland. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau, p. 109. [ii] Ofner, Lucia: Ich bin ein britisches Besatzungskind. In: Stelzl-Marx, Barbara & Satjukow, Silke (Eds.). (2015): Besatzungskinder. Die Nachkommen alliierter Soldaten in Österreich und Deutschland. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau, p. 465. [iii] Cf. Wahl, Niko: Heim ins Land der Väter. URL: http://www.zeit.de/2010/52/A-Mischlingskinder [iv] Cf. Satjukow, Silke & Gries, Rainer. (2015): “Bankerte!” Besatzungskinder in Deutschland nach 1945. Frankfurt, New York: Campus Verlag, p. 14

FINNISH WOMEN, FOREIGN SOLDIERS AND THE AFTERMATH

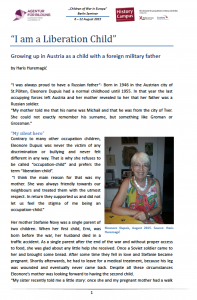

It took me nearly twenty years, to begin to wonder whether Finnish women had had children with the German and Soviet soldiers during WW II. To many Finns, the idea of a Finnish woman consorting with a Soviet or Nazi soldier evokes feelings of betrayal and shame. How did this reflect on the lives of the women and children in question?

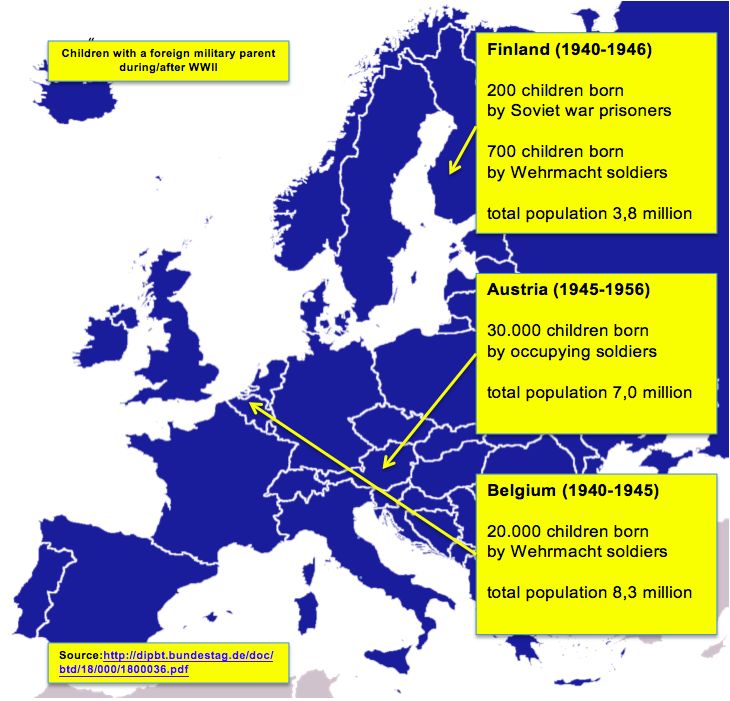

In Finland, children of foreign soldiers to Finnish mothers can be divided into two groups: those born to Finnish women and Soviet POWs (prisoners of war) in forced labour for Finnish agriculture, and those fathered by German soldiers in Finland during World War II.

Interestingly, as Lars Westerlund states in his article “Finnish Women who Consorted with Soviet Prisoners of War and their Children”, no children were reported born due to a rape committed by a Soviet soldier. Finnish women, lacking young men back home, had sexual relationships with Soviet POWs despite contemporary laws forbade it, resulting in an estimated two hundred children, chiefly fathered by high-ranking officers of wealthy academic background. Many officers were intelligent and skilled in languages or art, making them eligible bachelors, and their relatively good situation as labour force in rural Finland allowed prisoners to get in touch with locals. The prisoners were kept intentionally on meager nutrition to insure their dependence on army rations. The prisoners received gifts from their female Finnish admirers, however, such as rations, tobacco and bicycles. A large portion of these captured officers had wives and children back home and thus used their admirers mainly to improve their passable conditions. Although some of these imprisoned soldiers might have started a relationship for these gifts alone, most of the relationships were predominantly based on romance as numerous love letters and engagements can affirm.

Married women, who had children with Soviet POWs, were often divorced or worse when their men returned from fighting. On the other hand, single women were neglected and socially alienated for their alleged treasonous action, too. Their children experienced similar treatment, although children not conceived by adultery were eventually accepted by the community. Extramarital children and their parents, however, often met excessively cruel fates in the hands of the adulterer’s husband. For example, one new-born child was murdered immediately after birth and cast into a burning oven. Partially due to the mothers’ secrecy concerning their wartime romance, many of these children never got to know their father’s identity.

For the estimated 700 children conceived by German soldiers from 1940 to 1946, the situation was more challenging. The Nazis had lost and German people found themselves very unpopular. This reflected on their soldiers’ children abroad and manifested in taunts and alienation by native Finns. A few dozen were named after their fathers but the resulting torment harassment quickly led to renaming the children with Finnish names. Their mothers, however, were stigmatised for the rest of their lives and hence frequently treated like second-class citizens.

For the estimated 700 children conceived by German soldiers from 1940 to 1946, the situation was more challenging. The Nazis had lost and German people found themselves very unpopular. This reflected on their soldiers’ children abroad and manifested in taunts and alienation by native Finns. A few dozen were named after their fathers but the resulting torment harassment quickly led to renaming the children with Finnish names. Their mothers, however, were stigmatised for the rest of their lives and hence frequently treated like second-class citizens.

Considering the totality of the harassment the children of both Soviet and Nazi soldiers experienced, it is appalling how marginally the topic is discussed nowadays. Even though the children themselves could not affect their origin, they were guilted and punished for being born under wrong conditions. Perhaps due to the losses Finland suffered after losing the Continuation war and the hatred it stirred towards the victor the people were ashamed of these children. And still until this day, excluding the question of financial compensation for the families of Nazi soldiers raised nine years ago, the subject is yet to witness historical reappraisal.

LOVE OR HUNGER? – THE STRUGGLE FOR SURVIVAL OF THE BELGIAN FEMALE POPULATION

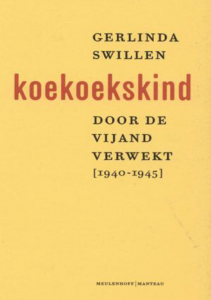

The fates of the occupation children has been a forgotten part of history in Belgium, too. I was surprised to find out that only one study exists on this topic in my country. Gerlinda Swillen’s book ‘Koekoekskind’ finally broke the taboo and started a public debate on this sensitive topic. Swillen had one particular aim while writing her work: to make people want to explore this piece of history more in depth. And that is exactly what she achieved with me. I watched TV-documentations about Belgian and Dutch occupation children and went to newspaper archives to search for articles about the topic from different decades.

The fates of the occupation children has been a forgotten part of history in Belgium, too. I was surprised to find out that only one study exists on this topic in my country. Gerlinda Swillen’s book ‘Koekoekskind’ finally broke the taboo and started a public debate on this sensitive topic. Swillen had one particular aim while writing her work: to make people want to explore this piece of history more in depth. And that is exactly what she achieved with me. I watched TV-documentations about Belgian and Dutch occupation children and went to newspaper archives to search for articles about the topic from different decades.

In the following paragraph I try to depict some circumstances that are specific for the situation of occupation children in my country.

During World War II, the population of Belgium suffered severely from the atrocities caused by the German occupation. The majority of the male population was either called for military service, or send to Germany to work in forced labour. Many Belgian women were left to their own devices, without a husband, at that time often the only breadwinner of the household, who took care of them. Because of that it was hard for them to make a living for themselves. They all found their own way of coping with the situation, for example being ‘very nice’ to the occupying forces to get food in times of starvation, and a warm bed to sleep on cold winter nights. But some of them, often as a consequence of a lack of human warmth, also just fell in love naturally with the handsome looking German men in uniform.

The relative luxury in which these women lived during the German occupation, evoked a feeling of envy among the starving Belgian people after the war. And when it became known that some of them even had children with the German occupying soldiers, an unprecedented fury broke out. The German soldiers had left, and the newly liberated country found itself in a state of lawlessness. So called ‘German whores’ were dragged out of their houses, their hair was shaven off and swastikas were drawn on their foreheads.

Later on many mothers moved to a different town for the sake of their children. They were afraid for their future, or as one mother put it: “I don’t want to have my child carry ‘an invisible swastika’ on his forehead for the rest of his life!” Unfortunately for the children, wherever they went the news about their background was spreading quickly. During their entire childhood the past haunted them, they were seen as ‘less’ than others. Bullying by peers, neglect by adults and even sometimes sexual abuse were common in their childhood. Even many years later those children still have enormous difficulties to talk about their past.

OUR CONCLUSION

The topic of “occupation children” is shaped by a huge variety of biographies. Still certain similarities can be pointed out and some differences of the national discussions, such as the motivations of women to start a relationship with a foreign soldier. The Finnish situation was remarkably different. Differing from Austria and Belgium, the women were the ones in a position to share their limited rations with the Soviet POWs. The poorly-rationed prisoners often fell in love with their benefactors forming relationships of varied permanence while others had merely frivolous affairs with the locals. Some prisoners were even “loving for food and shelter ”. This level of consorting was considered a treason by most, resulting in violent punishments and social isolation.

The children of German soldiers, however, became subject to discrimination for decades because of their father’s allegiance to the Nazis. Moreover, there is a profound difference in the question how this topic is discussed today. It’s important that we, as a post-war society, can distance ourselves to a certain extend from the irrationality that often comes along with war. By openly discussing this issue, it might become easier for the families involved to accept what has happened and to see it as a part of broader spectrum of historical circumstances. In Finland, there has been no remarkable public discussion on children of POWs in the past few years, partly because these children were few and far between. For the sake of historical curiosity and European integration alone, the matter should be more broadly discussed, however, while the discussion is still relevant. In Belgium, the public debate on occupation children is as well almost nonexistent.

The enormous taboo on this topic and Belgian collaboration in general, obstructs the living occupation children to step forward and share their stories. The complicated Belgian political situation makes it even worse, due to the rude polemic statements evoked by some parties. While in Belgium this issue is integrated in the wider discussion on collaboration, in Austria it is a topic of its own. In the last ten years it has gained more and more attention and raised awareness for similar phenomena in present war-like conflicts.The task for the future is to develop concrete international principles on how to help children born to a foreign military father in present conflicts.

Given that many fathers also happen to be UN-soldiers, the United Nations should devote itself more to this important topic. In addition, the time has come to bring to mind what can be gained from those children. As they have boundaries to two nations, they can be seen as potential catalyzer of reconciliation between “enemy-states”, such as in Europe those children have ties to more than one nation and thus can be seen as an incarnation of the European idea. The fact that those children are not considered as “enemy’s children” anymore is one of the countless achievements of the European idea. Let us consider those children as one symbol for Europe – a symbol we desperately need in these days.

Haris Huremagić

Haris Huremagić

born 1994 in Austria with Bosnian roots, law student, likes debating about music, philosophy, politics but becomes most passionate about historical topics. Haris adores hot chocolate, you are free to invite him in Vienna.

Jani Patrakka

Jani Patrakka

born 1995 in Finland is a technical university student in Tampere. Besides his devout interest in history and politics, Jani loves music, acting, debating and cooking. If you share his interest in philosophy, languages, mathematics or virtually any field of science in general, feel free to share your thoughts with him.

Thomas Dirven

Thomas Dirven

(born in 1998) still attends high school. He lives near Antwerp in Belgium. When he listens to people’s stories, he loves passing them on to others. One of the things he certainly wants to do before he dies, is to write his own book.

Dot Low

I am Scottish and know my father serving in WW2 fathered a son in Belgium. I even have a picture of him. We found the photo when clearing out the house. My brother said ‘ Which one of us is that’ as he looks like 2 of my brothers. My sister and I were only ones who knew so told rest of family- he is your brother Jacques! I feel sad that he probably grew up never knowing he has brothers and sisters in UK.

Nelda Miller

My father was a U.S. soldier in Ww11.He always talked to me about Helena the Belgian girl he loved and left behind after the war.My mother told me he wanted to bring he back to the States but the army wouldn’t let him.I wish he had told me more a last name or the name of the city.Helena was pregnant and still breaks my heart he had to leave her and the baby behind.Hr always told me the Belgian people were very kind even during war times.Apparrently it was just Helena her sister and their daddy.He said they lived in a city with a huge staircase like an auger.I wish I knew more.Helena may have passed away,maybe the child to but her memory was always in my daddy’s heart..Sgt Dennis Grant Miller of the U.S.Army WW11.

Sheila Chapman

My father told me before he did that he had fathered a son with a woman who lived in Austria. I don’t know her name – only that she was an opera singer. He had spoken of the “opera singer” fondly for all my life but I did not know about my half- brother until just before my dad passed away. I would love to have a way to find him but given the small amount of information I have, I don’t know where to begin. Howard Thomas was my dad’s name.

Lisa

Do you have any contact information for Gerlinda Swillen?

Fiona

Dear Lisa, we are not in touch with her personally. Sorry. All the best!

Gill Oats

Hi Lisa yes I do. gerlinda.swillen @skynet. Hope she can help you.

Allison Knapp

My grandfather, William Hunt, stayed with the Persoons family in Brussels (1942 to 45) during the war. They had a daughter Simone. My father believes that he has a sister but doesn’t have any details. We are doing what we can to see if this is the case and make contact. If anyone reads this and could shed any light it would be appreciated.

Ron Stone

My father, Elmer Lee Stone, fathered a child from a lady who escaped Austria during WE2. I would like to know about my half sibling. This happened in Germany in 1945-1946.

Gill Oats

My father Harold Smith of the Cameronians stayed with Maria Desimpel,Poperingestraat 4 Roesbrugge Belgie during the 2nd World War. I believe her father or brother was Jozef. My father believed he fathered a baby with Maria,a boy he thought. My half brother. Any information would be greatly appreciated.